Duterte’s deadly legacy and the desperate pleas for justice | ABS-CBN

ADVERTISEMENT

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

Duterte’s deadly legacy and the desperate pleas for justice

Duterte’s deadly legacy and the desperate pleas for justice

Mike Navallo,

ABS-CBN News

Published Jul 14, 2022 01:01 PM PHT

|

Updated Jul 15, 2022 06:34 PM PHT

Third of a series on the legacy of the Duterte administration

THE KILLING

“May dugo.” (There’s blood.)

“May dugo.” (There’s blood.)

A voice could clearly be heard in a video recording of a 2016 drug operation in Pasay City.

A voice could clearly be heard in a video recording of a 2016 drug operation in Pasay City.

Then a warning that came with a gunshot: “Huwag kayong makialam.” (Do not interfere.)

Then a warning that came with a gunshot: “Huwag kayong makialam.” (Do not interfere.)

“Ito po, ito po, susuko na po (I’m going to surrender),” said a faint voice in the recording, only to be drowned out by rapid, successive gunfire.

“Ito po, ito po, susuko na po (I’m going to surrender),” said a faint voice in the recording, only to be drowned out by rapid, successive gunfire.

ADVERTISEMENT

By the end of the recording, 22-year-old pedicab driver Eric Sison is dead, yet another casualty at the beginning of a drug war that would later claim thousands of lives in a span of six years.

By the end of the recording, 22-year-old pedicab driver Eric Sison is dead, yet another casualty at the beginning of a drug war that would later claim thousands of lives in a span of six years.

It was August 23, 2016. Former President Rodrigo Duterte was on the second month of a campaign promise to eradicate illegal drug use in 3 to 6 months, vowing to go after drug users and pushers and threatening to dump as many as 100,000 of them on Manila Bay.

It was August 23, 2016. Former President Rodrigo Duterte was on the second month of a campaign promise to eradicate illegal drug use in 3 to 6 months, vowing to go after drug users and pushers and threatening to dump as many as 100,000 of them on Manila Bay.

The killings started soon after he was elected into office in May and intensified as soon as he was sworn in on June 30, 2016.

The killings started soon after he was elected into office in May and intensified as soon as he was sworn in on June 30, 2016.

By August of that year, the number of bodies either found dead or killed in police operations started to pile up on the streets of Metro Manila, and the nightly news would be dominated by reports of slain drug suspects killed because they allegedly resisted arrest and fought back in what became locally known as “nanlaban.”

By August of that year, the number of bodies either found dead or killed in police operations started to pile up on the streets of Metro Manila, and the nightly news would be dominated by reports of slain drug suspects killed because they allegedly resisted arrest and fought back in what became locally known as “nanlaban.”

“Alma” (real identity concealed upon request) never thought her live-in partner Eric would end up among the statistics.

“Alma” (real identity concealed upon request) never thought her live-in partner Eric would end up among the statistics.

She recalled asking him for money for dinner and the next time she saw him, he was bleeding as he rushed towards the roof of the three-story building they were residing in.

She recalled asking him for money for dinner and the next time she saw him, he was bleeding as he rushed towards the roof of the three-story building they were residing in.

His last words, she said, were: “Huwag na raw po siyang sundan kasi nakita po niya yung anak ko na natutulog (He told me not to follow him because he saw our son sleeping).”

His last words, she said, were: “Huwag na raw po siyang sundan kasi nakita po niya yung anak ko na natutulog (He told me not to follow him because he saw our son sleeping).”

Eric and Alma’s son had just turned one-year-old at that time.

Eric and Alma’s son had just turned one-year-old at that time.

Police said they were conducting foot patrol in Barangay 43 in Pasay when they spotted Eric talking to a man. He allegedly drew out a gun, fired at them, and was hit when police returned fire.

Police said they were conducting foot patrol in Barangay 43 in Pasay when they spotted Eric talking to a man. He allegedly drew out a gun, fired at them, and was hit when police returned fire.

He then supposedly ran to a three-story building, jumped over to the roof of another house where he was surrounded.

He then supposedly ran to a three-story building, jumped over to the roof of another house where he was surrounded.

“[W]hen the suspect was cornered, he chose to fight it out by pointing his gun upon the pursuing team but his action was prevented; instead, he was neutralized by the pursuing police officers,” read a portion of the police incident report.

“[W]hen the suspect was cornered, he chose to fight it out by pointing his gun upon the pursuing team but his action was prevented; instead, he was neutralized by the pursuing police officers,” read a portion of the police incident report.

The report also said the police recovered a .38-caliber revolver with ammunitions and 2 pieces of transparent plastic with suspected shabu or methamphetamine, and 4 sachets of dried marijuana leaves.

The report also said the police recovered a .38-caliber revolver with ammunitions and 2 pieces of transparent plastic with suspected shabu or methamphetamine, and 4 sachets of dried marijuana leaves.

But Alma, and several other neighbors who executed sworn statements, said Eric did not own a gun and neither did he use nor sell illegal drugs. And she swore it was Eric’s voice caught in a cellphone video recording saying he would surrender. “Boses ng asawa ko ‘yun (It was my husband’s voice),” she said.

But Alma, and several other neighbors who executed sworn statements, said Eric did not own a gun and neither did he use nor sell illegal drugs. And she swore it was Eric’s voice caught in a cellphone video recording saying he would surrender. “Boses ng asawa ko ‘yun (It was my husband’s voice),” she said.

“Bakit po ganun ang ginawa nila sa asawa ko? Sumuko na nga po asawa ko, di pa nila binigyan ng chance,” she asked.

“Bakit po ganun ang ginawa nila sa asawa ko? Sumuko na nga po asawa ko, di pa nila binigyan ng chance,” she asked.

(Why did they do that to my partner? He already surrendered. Why did they not give him a chance?)

(Why did they do that to my partner? He already surrendered. Why did they not give him a chance?)

The cellphone video quickly made the rounds on social media, described by many as an “overkill.” It was also heavily covered by traditional media.

The cellphone video quickly made the rounds on social media, described by many as an “overkill.” It was also heavily covered by traditional media.

It was one of the first drug war incidents with a rare video recording that showed potential excesses in police drug operations.

It was one of the first drug war incidents with a rare video recording that showed potential excesses in police drug operations.

Then-Senator Leila de Lima, who spearheaded a probe into Duterte’s drug war at that time, called the incident “a summary execution” and vowed to include it in her probe.

Then-Senator Leila de Lima, who spearheaded a probe into Duterte’s drug war at that time, called the incident “a summary execution” and vowed to include it in her probe.

The National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) found that Eric sustained 14 gunshot wounds – some of them on vital organs such as the head and the neck, which were fatal.

The National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) found that Eric sustained 14 gunshot wounds – some of them on vital organs such as the head and the neck, which were fatal.

The agency also said the gun was planted and went on to file a murder complaint, but the local prosecutor disagreed and lowered the criminal charge to homicide.

The agency also said the gun was planted and went on to file a murder complaint, but the local prosecutor disagreed and lowered the criminal charge to homicide.

Three police officers were charged with homicide in September 2017 but in less than a year, a Pasay court provisionally dismissed the case in August 2018 because of the absence of the complainant. A provisional dismissal becomes final after 2 years.

Three police officers were charged with homicide in September 2017 but in less than a year, a Pasay court provisionally dismissed the case in August 2018 because of the absence of the complainant. A provisional dismissal becomes final after 2 years.

The testimony of the person who took the cellphone video was also stricken out because he supposedly did not see the incident.

The testimony of the person who took the cellphone video was also stricken out because he supposedly did not see the incident.

Alma had thought the cellphone video was a strong evidence against the police and would have wanted to pursue the case.

Alma had thought the cellphone video was a strong evidence against the police and would have wanted to pursue the case.

But Eric’s mother entered into a deal with the perpetrators.

But Eric’s mother entered into a deal with the perpetrators.

“Kung tutuusin po talaga, ilalaban po talaga namin… Kaso binayaran po, inunahan po ng nanay. Hiningan ng isandaang libo. Tapos nung maghi-hearing na, inawat na po ako. Papasok na po ako ng City Hall…sabi wala na daw pong hearing,” she said.

“Kung tutuusin po talaga, ilalaban po talaga namin… Kaso binayaran po, inunahan po ng nanay. Hiningan ng isandaang libo. Tapos nung maghi-hearing na, inawat na po ako. Papasok na po ako ng City Hall…sabi wala na daw pong hearing,” she said.

(If I had it my way, I would fight for the case. But Eric’s mother agreed to be paid. She asked for a hundred thousand pesos. And when the case was about to be heard, she stopped me from entering the city hall and told me there won’t be any more hearings.)

(If I had it my way, I would fight for the case. But Eric’s mother agreed to be paid. She asked for a hundred thousand pesos. And when the case was about to be heard, she stopped me from entering the city hall and told me there won’t be any more hearings.)

Eric’s mother refused to give any statement but confirmed to ABS-CBN News that they agreed to settle the case out of fear of the police.

Eric’s mother refused to give any statement but confirmed to ABS-CBN News that they agreed to settle the case out of fear of the police.

DRUG WAR DEATHS

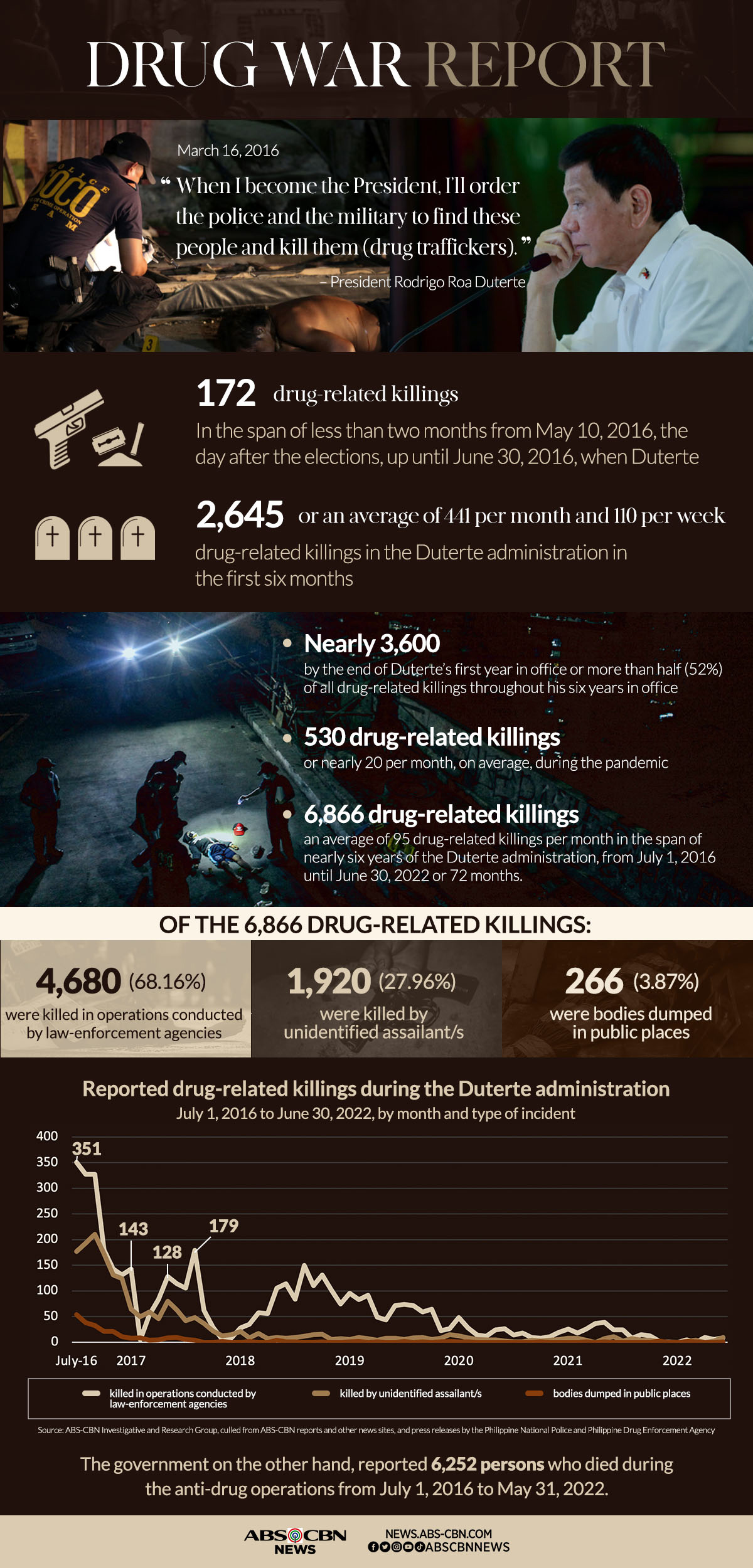

Official figures from the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) and the Philippine National Police (PNP) place the number of deaths as a result of drug operations in the Philippines since July 1, 2016 at 6,241.

Official figures from the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) and the Philippine National Police (PNP) place the number of deaths as a result of drug operations in the Philippines since July 1, 2016 at 6,241.

The PNP used to indicate a separate entry for deaths under investigation but soon dropped the category with media and human rights groups keeping their own tabs on the death toll attributed to vigilante-style killings and unknown perpetrators.

The PNP used to indicate a separate entry for deaths under investigation but soon dropped the category with media and human rights groups keeping their own tabs on the death toll attributed to vigilante-style killings and unknown perpetrators.

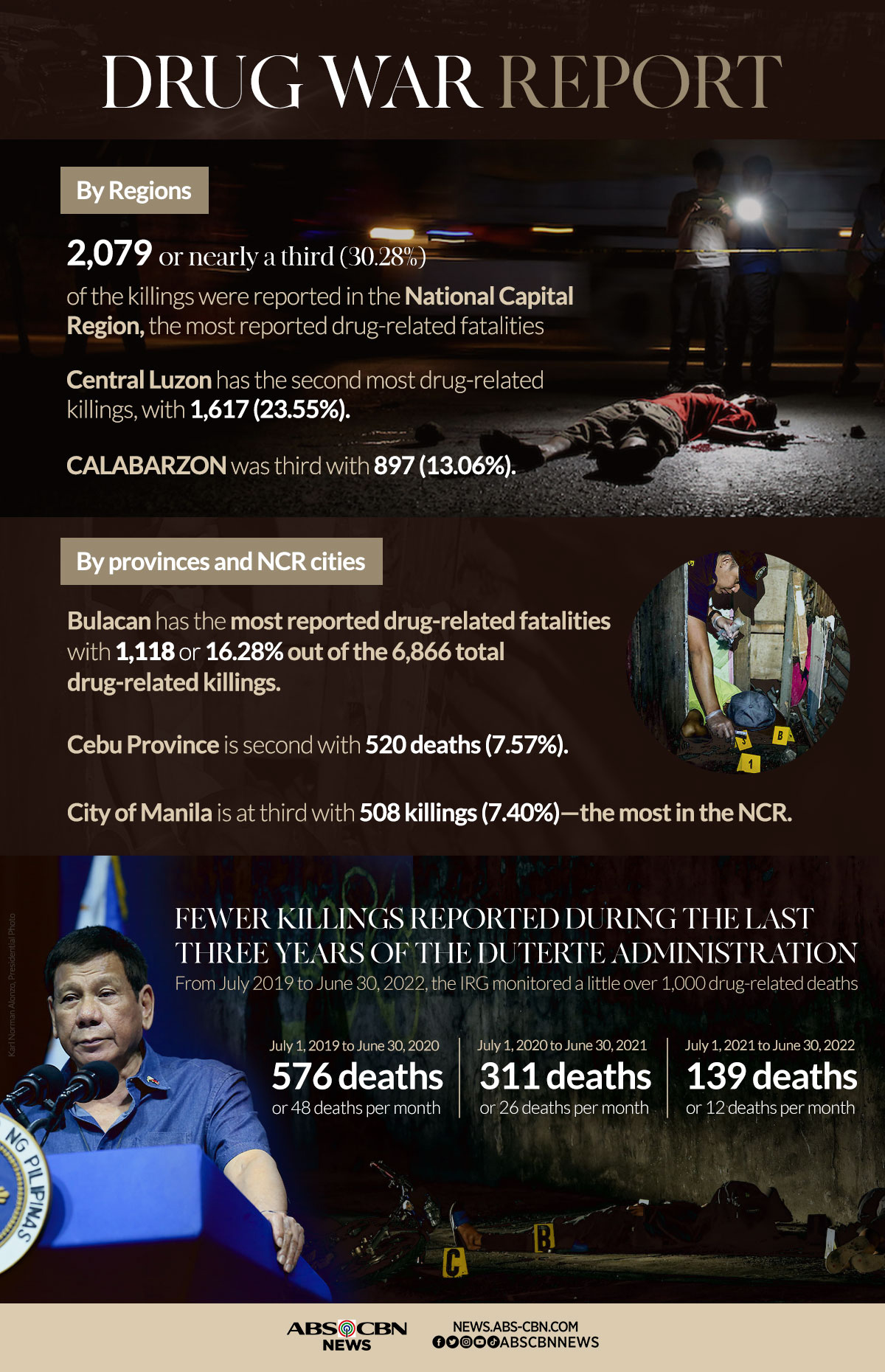

The ABS-CBN Investigative and Research Group monitored 7,009 drug-related deaths from media reports and official press releases since May 10, 2016, when it became clear Duterte had won the presidency.

The ABS-CBN Investigative and Research Group monitored 7,009 drug-related deaths from media reports and official press releases since May 10, 2016, when it became clear Duterte had won the presidency.

More than 68 percent or 4,780 were killed in drug operations. Almost 28 percent or 1,949 persons were killed by unidentified suspects while almost 4 percent or 280 bodies were dumped in public places.

More than 68 percent or 4,780 were killed in drug operations. Almost 28 percent or 1,949 persons were killed by unidentified suspects while almost 4 percent or 280 bodies were dumped in public places.

A 2022 Commission on Human Rights (CHR) report which examined 798 incidents of drug-related killings showed 60 percent of the deaths took place during drug operations, 30 percent were killed by unidentified persons while 9 percent had unclear information.

A 2022 Commission on Human Rights (CHR) report which examined 798 incidents of drug-related killings showed 60 percent of the deaths took place during drug operations, 30 percent were killed by unidentified persons while 9 percent had unclear information.

The highest number of drug-related deaths took place during Duterte’s first year in office, with nearly 300 alleged drug suspects killed each month.

The highest number of drug-related deaths took place during Duterte’s first year in office, with nearly 300 alleged drug suspects killed each month.

Human rights groups estimate, the real number could go higher than 30,000 – unprecedented in the eyes of the human rights commission.

Human rights groups estimate, the real number could go higher than 30,000 – unprecedented in the eyes of the human rights commission.

“[In] every administration, we’ve had our share of high-profile cases. Meron namang mga killings, meron ding enforced disappearances and torture. Kaya lang yung rate at saka yung scale was different with regard to the campaign against drugs. Mataas at marami, at halos on a daily basis nangyayari ang mga patayan noon in relation to the war on drugs,” said CHR executive director Jacqueline Ann de Guia.

“[In] every administration, we’ve had our share of high-profile cases. Meron namang mga killings, meron ding enforced disappearances and torture. Kaya lang yung rate at saka yung scale was different with regard to the campaign against drugs. Mataas at marami, at halos on a daily basis nangyayari ang mga patayan noon in relation to the war on drugs,” said CHR executive director Jacqueline Ann de Guia.

(In every administration, we’ve had our share of high-profile cases. There were killings, enforced disappearances and torture. But the rate and scale was different with regard to the campaign against drugs. The rate was high and there were many killings that happened almost on a daily basis.)

(In every administration, we’ve had our share of high-profile cases. There were killings, enforced disappearances and torture. But the rate and scale was different with regard to the campaign against drugs. The rate was high and there were many killings that happened almost on a daily basis.)

But the actual number of deaths due to the drug war might never be known.

But the actual number of deaths due to the drug war might never be known.

“Up until now that remains to be a question,” De Guia said. “At the end of the day, one life is too many and it’s really serious.”

“Up until now that remains to be a question,” De Guia said. “At the end of the day, one life is too many and it’s really serious.”

Half-way through the Duterte administration in May 2019, the PNP already reported 6,600 drug personalities killed in police operations. By July, they revised that number to 5,526.

Half-way through the Duterte administration in May 2019, the PNP already reported 6,600 drug personalities killed in police operations. By July, they revised that number to 5,526.

Going by the official figure of 6,241, only around 700 cases were added in the next 3 years.

Going by the official figure of 6,241, only around 700 cases were added in the next 3 years.

The DOJ, which is conducting a drug war review, adopts the PNP and PDEA figures.

The DOJ, which is conducting a drug war review, adopts the PNP and PDEA figures.

PATTERN

By ABS-CBN Investigative and Research Group's monitoring, the capital region had the most number of drug-war deaths recorded, followed by Central Luzon and the CALABARZON region. Most of the CHR’s investigations also concentrated in these 3 regions.

By ABS-CBN Investigative and Research Group's monitoring, the capital region had the most number of drug-war deaths recorded, followed by Central Luzon and the CALABARZON region. Most of the CHR’s investigations also concentrated in these 3 regions.

Bulacan topped the list among the 81 provinces in the country.

Bulacan topped the list among the 81 provinces in the country.

Within the National Capital Region, the cities of Manila, Quezon City and Caloocan figured prominently.

Within the National Capital Region, the cities of Manila, Quezon City and Caloocan figured prominently.

What emerged from the killings is a pattern of mostly male victims who come from poor backgrounds who allegedly fought back even as family members claim they were too poor to own a gun.

What emerged from the killings is a pattern of mostly male victims who come from poor backgrounds who allegedly fought back even as family members claim they were too poor to own a gun.

The human rights commission’s report showed 83 percent of those killed were male while more than half of the victims were aged 25 to 44. Most of them were either unemployed or worked as laborers, drivers, farmers and fisherfolk.

The human rights commission’s report showed 83 percent of those killed were male while more than half of the victims were aged 25 to 44. Most of them were either unemployed or worked as laborers, drivers, farmers and fisherfolk.

“We do have a reason to believe that the poor really was a victim in this campaign against drugs. Many were from low-income families, many were breadwinners. In fact, one of the problems left by the campaign against drugs was the widows and the orphans who were left. Because clearly, those who were killed were the breadwinners or the income-earners in the family and there was no program para sa kanila noong kahuli-hulihan (In the end, there was no program for them),” De Guia said.

“We do have a reason to believe that the poor really was a victim in this campaign against drugs. Many were from low-income families, many were breadwinners. In fact, one of the problems left by the campaign against drugs was the widows and the orphans who were left. Because clearly, those who were killed were the breadwinners or the income-earners in the family and there was no program para sa kanila noong kahuli-hulihan (In the end, there was no program for them),” De Guia said.

Eric’s was not the only case where investigating authorities cast doubt on whether a drug suspect was armed.

Eric’s was not the only case where investigating authorities cast doubt on whether a drug suspect was armed.

A June 2020 report by the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights found that based on an examination of 25 operations in Metro Manila between August 2016 and June 2017, “police repeatedly recovered guns bearing the same serial numbers from different victims in different locations.”

A June 2020 report by the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights found that based on an examination of 25 operations in Metro Manila between August 2016 and June 2017, “police repeatedly recovered guns bearing the same serial numbers from different victims in different locations.”

The report suggested victims were unarmed at the time of the killing and the guns supposedly recovered from suspects were planted.

The report suggested victims were unarmed at the time of the killing and the guns supposedly recovered from suspects were planted.

A drug war review led by the Philippines' Department of Justice (DOJ) found that in 52 cases it examined, there was no proper probe into the ownership of the weapons allegedly recovered from drug suspects and some of the standard tests were not conducted.

A drug war review led by the Philippines' Department of Justice (DOJ) found that in 52 cases it examined, there was no proper probe into the ownership of the weapons allegedly recovered from drug suspects and some of the standard tests were not conducted.

“Walang paraffin test. Walang ballistics test. Walang death certificate. Minsan wala man lang coordination with SOCO [Scene of the Crime Operatives]. Autopsy wala. So maraming kulang talaga. And in fact, ang isa pa, madalas na nakikita namin, yun normal yan so iti-trace mo ang ownership ng mga baril, walang ganun,” former Justice Undersecretary Adrian Sugay said.

“Walang paraffin test. Walang ballistics test. Walang death certificate. Minsan wala man lang coordination with SOCO [Scene of the Crime Operatives]. Autopsy wala. So maraming kulang talaga. And in fact, ang isa pa, madalas na nakikita namin, yun normal yan so iti-trace mo ang ownership ng mga baril, walang ganun,” former Justice Undersecretary Adrian Sugay said.

Both the CHR and the DOJ also found violations of police protocols.

Both the CHR and the DOJ also found violations of police protocols.

But an even more disturbing pattern – the injuries sustained by slain drug war suspects in supposed legitimate drug operations indicate there was intent to kill, according to the CHR.

But an even more disturbing pattern – the injuries sustained by slain drug war suspects in supposed legitimate drug operations indicate there was intent to kill, according to the CHR.

Of the 235 victims with gunshot wounds that it examined, 201 or 85 percent were shot in the head and/or the torso.

Of the 235 victims with gunshot wounds that it examined, 201 or 85 percent were shot in the head and/or the torso.

The DOJ’s own review found multiple gunshot wounds in almost half of the cases it reviewed, with one suspect sustaining no less than 15 gunshot wounds on the head, trunk, and upper and lower extremities.

The DOJ’s own review found multiple gunshot wounds in almost half of the cases it reviewed, with one suspect sustaining no less than 15 gunshot wounds on the head, trunk, and upper and lower extremities.

Eric had 14 gunshot wounds, some on the neck and on the head.

Eric had 14 gunshot wounds, some on the neck and on the head.

“The number indicates that there’s intent to kill. The location, because most of it were in fatal parts of the body. And then of course nakita din natin yung use of superior strength. In most of the cases, syempre, iisa lang yung victim kaya lang three yung operatives on the average. And ang point natin is, the three policemen were outnumbering clearly the victims and had the advantage of superior firearms and training and all that,” De Guia said.

“The number indicates that there’s intent to kill. The location, because most of it were in fatal parts of the body. And then of course nakita din natin yung use of superior strength. In most of the cases, syempre, iisa lang yung victim kaya lang three yung operatives on the average. And ang point natin is, the three policemen were outnumbering clearly the victims and had the advantage of superior firearms and training and all that,” De Guia said.

“And the PNP Manual of Operations would say that, you know, fire shots that will disable, not kill. But of course the location and the number of gunshot wounds would indicate that that is to the contrary,” she added.

“And the PNP Manual of Operations would say that, you know, fire shots that will disable, not kill. But of course the location and the number of gunshot wounds would indicate that that is to the contrary,” she added.

Sugay said the burden of explaining the circumstances behind a suspect’s death falls on the law enforcers.

Sugay said the burden of explaining the circumstances behind a suspect’s death falls on the law enforcers.

“May namatay di ba? Kunyari may nagdemanda, nagdemanda yung mga kaanak, so syempre pag ganun, may namatay e. So bakit namatay? How do you justify the killing or death? Anong nangyari? Nanlaban? Ganun ba? Anong nangyari? How do you justify? Was it properly documented? Kasi ganyan naman yung mga operations dapat di ba? Maski nga walang namatay, when you talk about drugs, meron dapat chain of custody. Kailangan fully documented. I guess lalo na kapag may namatay,” he said.

“May namatay di ba? Kunyari may nagdemanda, nagdemanda yung mga kaanak, so syempre pag ganun, may namatay e. So bakit namatay? How do you justify the killing or death? Anong nangyari? Nanlaban? Ganun ba? Anong nangyari? How do you justify? Was it properly documented? Kasi ganyan naman yung mga operations dapat di ba? Maski nga walang namatay, when you talk about drugs, meron dapat chain of custody. Kailangan fully documented. I guess lalo na kapag may namatay,” he said.

THE LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE

But getting law enforcers to explain in Philippine courts what exactly happened to a drug war suspect, much less secure a conviction, is a long shot.

But getting law enforcers to explain in Philippine courts what exactly happened to a drug war suspect, much less secure a conviction, is a long shot.

By CHR’s count, only 20 of the more than 3,000 drug -war killings it has investigated so far have reached the courts for criminal prosecution.

By CHR’s count, only 20 of the more than 3,000 drug -war killings it has investigated so far have reached the courts for criminal prosecution.

More than 60 other cases are either with the Office of the Ombudsman or the prosecutors for preliminary investigation – the step prior to filing of criminal charges in court – while more than a hundred other administrative cases are being investigated by either the Ombudsman or the Internal Affairs Service.

More than 60 other cases are either with the Office of the Ombudsman or the prosecutors for preliminary investigation – the step prior to filing of criminal charges in court – while more than a hundred other administrative cases are being investigated by either the Ombudsman or the Internal Affairs Service.

Some of the few cases that reach the courts remain idle for years, like the case of Renato and Jaypee Bertes, father-and-son drug suspects who were killed inside a Pasay police station in July 2016.

Some of the few cases that reach the courts remain idle for years, like the case of Renato and Jaypee Bertes, father-and-son drug suspects who were killed inside a Pasay police station in July 2016.

Jaypee was accused of drug peddling while his father was arrested with him in a late night raid because he didn’t want to let go of his son.

Jaypee was accused of drug peddling while his father was arrested with him in a late night raid because he didn’t want to let go of his son.

They allegedly tried to grab a police officer’s gun while outside a detention cell and were killed as a result.

They allegedly tried to grab a police officer’s gun while outside a detention cell and were killed as a result.

But the CHR’s investigation showed they were beaten before they were shot.

But the CHR’s investigation showed they were beaten before they were shot.

The Senate held its own probe and the PNP filed 2 murder charges against 2 police officers involved.

The Senate held its own probe and the PNP filed 2 murder charges against 2 police officers involved.

Warrants of arrest were issued but to this day, the police officers remain at large. The 2 murder cases were archived in August 2017 and June 2019.

Warrants of arrest were issued but to this day, the police officers remain at large. The 2 murder cases were archived in August 2017 and June 2019.

The long period that has elapsed since the killings also pose additional challenges to victims and their families – from lost evidence and documents to witnesses withdrawing from the case or switching sides.

The long period that has elapsed since the killings also pose additional challenges to victims and their families – from lost evidence and documents to witnesses withdrawing from the case or switching sides.

Mariza Hamoy’s 17-year-old son, Darwin, was killed in a birthday party in August 2016, in what police called another “nanlaban” incident during a buy-bust operation.

Mariza Hamoy’s 17-year-old son, Darwin, was killed in a birthday party in August 2016, in what police called another “nanlaban” incident during a buy-bust operation.

But witnesses said there was no shootout, only police officers raiding a house and killing 4 unarmed men, including Darwin.

But witnesses said there was no shootout, only police officers raiding a house and killing 4 unarmed men, including Darwin.

Hamoy’s quest for justice brought her to the Office of the Ombusdman and the PNP Internal Affairs Service (IAS).

Hamoy’s quest for justice brought her to the Office of the Ombusdman and the PNP Internal Affairs Service (IAS).

But the Ombudsman junked her case in 2019 while in June this year, she received notice from the Office of the President that her IAS complaint against the head of the so-called “Davao boys” has been dismissed.

But the Ombudsman junked her case in 2019 while in June this year, she received notice from the Office of the President that her IAS complaint against the head of the so-called “Davao boys” has been dismissed.

The reason: her 2 fellow-complainants moved to withdraw the case, with one of them retracting an earlier statement she witnessed the encounter, a common experience in many other cases.

The reason: her 2 fellow-complainants moved to withdraw the case, with one of them retracting an earlier statement she witnessed the encounter, a common experience in many other cases.

“Witnesses were very hesitant to come forward. Victims were afraid because they had to face either alleged policemen as respondents or vigilante killers who were up, until this day, left unidentified. And if you understand that situation, you would now understand how difficult it was and it is for the cases to progress. There has to be an enabling environment to be created by the government where trust will have to be built,” De Guia said.

“Witnesses were very hesitant to come forward. Victims were afraid because they had to face either alleged policemen as respondents or vigilante killers who were up, until this day, left unidentified. And if you understand that situation, you would now understand how difficult it was and it is for the cases to progress. There has to be an enabling environment to be created by the government where trust will have to be built,” De Guia said.

The DOJ has a Witness Protection Program but Sugay said it has not yet received any requests from potential witnesses in the cases that they have reviewed.

The DOJ has a Witness Protection Program but Sugay said it has not yet received any requests from potential witnesses in the cases that they have reviewed.

“As far as I know, none of the witnesses have been admitted or asked for admission into the Witness Protection Program. We foresee that if this continues, that if the NBI continues with the case buildup and investigation into these cases, that in all likelihood that some of these witnesses may ask for protection considering that as we know, when we talk about review of the drug war, the review that we have undertaken, this almost always involves members of law enforcement,” he said.

“As far as I know, none of the witnesses have been admitted or asked for admission into the Witness Protection Program. We foresee that if this continues, that if the NBI continues with the case buildup and investigation into these cases, that in all likelihood that some of these witnesses may ask for protection considering that as we know, when we talk about review of the drug war, the review that we have undertaken, this almost always involves members of law enforcement,” he said.

Both the DOJ and the CHR admit the case of 17-year-old Kian Lloyd delos Santos, killed by three cops in Caloocan in August 2017, is the only instance so far where police officers were held accountable.

Both the DOJ and the CHR admit the case of 17-year-old Kian Lloyd delos Santos, killed by three cops in Caloocan in August 2017, is the only instance so far where police officers were held accountable.

Police claimed Delos Santos was shot after he resisted arrest. But a surveillance camera footage showed he was dragged into a dark alley.

Police claimed Delos Santos was shot after he resisted arrest. But a surveillance camera footage showed he was dragged into a dark alley.

Several witnesses testified the police handed Delos Santos a gun and told him to run before firing at him.

Several witnesses testified the police handed Delos Santos a gun and told him to run before firing at him.

The autopsy result showed Delos Santos suffered gunshot wounds to the head while he was already kneeling on the ground.

The autopsy result showed Delos Santos suffered gunshot wounds to the head while he was already kneeling on the ground.

The incident received considerable media mileage and congressional probes, which led to a temporary halt to Oplan Tokhang, the police’s campaign for low-level drug personalities.

The incident received considerable media mileage and congressional probes, which led to a temporary halt to Oplan Tokhang, the police’s campaign for low-level drug personalities.

Unlike Eric’s case, the 3 cops were found guilty of murdering Delos Santos in a just a little over a year – in November 2018.

Unlike Eric’s case, the 3 cops were found guilty of murdering Delos Santos in a just a little over a year – in November 2018.

The conviction in Delos Santos’ case became the face of the Philippine government’s claim that it was investigating the drug-war killings and international bodies like the International Criminal Court (ICC) need not step in.

The conviction in Delos Santos’ case became the face of the Philippine government’s claim that it was investigating the drug-war killings and international bodies like the International Criminal Court (ICC) need not step in.

Former ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda opened a preliminary examination on the situation in the Philippines in February 2018 and by May last year, she recommended launching a full probe on the drug-war killings and the Davao Death squad, alleged to be the precursor of the anti-drug campaign.

Former ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda opened a preliminary examination on the situation in the Philippines in February 2018 and by May last year, she recommended launching a full probe on the drug-war killings and the Davao Death squad, alleged to be the precursor of the anti-drug campaign.

An ICC Pre-Trial Chamber gave the go-signal in September but the Philippine government asked for a deferral citing its own drug war review headed by the DOJ.

An ICC Pre-Trial Chamber gave the go-signal in September but the Philippine government asked for a deferral citing its own drug war review headed by the DOJ.

In June this year, ICC Prosecutor Karim Khan sought to resume the probe. He rejected the Philippine government’s claim that it was probing the killings, calling the DOJ initiative a mere “desk review” which touched on 52 cases or only a small fraction out of the thousands killed in the drug war and did not involve criminal prosecutions.

In June this year, ICC Prosecutor Karim Khan sought to resume the probe. He rejected the Philippine government’s claim that it was probing the killings, calling the DOJ initiative a mere “desk review” which touched on 52 cases or only a small fraction out of the thousands killed in the drug war and did not involve criminal prosecutions.

Khan also pointed out, “investigations” in the Philippines did not look into whether the killings were part of a state policy and did not go all the way up to senior law enforcement officials, accused of taking part in the planning and execution of the killings, and to Duterte himself, accused of encouraging them.

Khan also pointed out, “investigations” in the Philippines did not look into whether the killings were part of a state policy and did not go all the way up to senior law enforcement officials, accused of taking part in the planning and execution of the killings, and to Duterte himself, accused of encouraging them.

In authorizing the probe last year, the ICC Pre-Trial Chamber had said “the so-called 'war on drugs' campaign cannot be seen as a legitimate law enforcement operation, and the killings neither as legitimate nor as mere excesses in an otherwise legitimate operation. Rather, the available material indicates, to the required standard, that a widespread and systematic attack against the civilian population took place pursuant to or in furtherance of a State policy.”

In authorizing the probe last year, the ICC Pre-Trial Chamber had said “the so-called 'war on drugs' campaign cannot be seen as a legitimate law enforcement operation, and the killings neither as legitimate nor as mere excesses in an otherwise legitimate operation. Rather, the available material indicates, to the required standard, that a widespread and systematic attack against the civilian population took place pursuant to or in furtherance of a State policy.”

The UN Human Rights Office (OHCHR) in its June 2020 report examined key policy documents on the drug war which used the term “neutralization” of drug suspects, an “ill-defined and ominous” language, it said which, when coupled with “repeated verbal encouragement” by high-ranking officials to use lethal force, “may have emboldened police to treat the circular as permission to kill.”

The UN Human Rights Office (OHCHR) in its June 2020 report examined key policy documents on the drug war which used the term “neutralization” of drug suspects, an “ill-defined and ominous” language, it said which, when coupled with “repeated verbal encouragement” by high-ranking officials to use lethal force, “may have emboldened police to treat the circular as permission to kill.”

But the DOJ and the Philippine government continues to assert, domestic accountability mechanisms are working and again cited its own drug-war review.

But the DOJ and the Philippine government continues to assert, domestic accountability mechanisms are working and again cited its own drug-war review.

The review itself has been criticized as an attempt to avoid a full-blown international probe by another body, the UN Human Rights Council, which decided in October 2020 to instead support human rights efforts in the Philippines, after no less than former Justice Secretary Menardo Guevarra touted the drug-war review.

The review itself has been criticized as an attempt to avoid a full-blown international probe by another body, the UN Human Rights Council, which decided in October 2020 to instead support human rights efforts in the Philippines, after no less than former Justice Secretary Menardo Guevarra touted the drug-war review.

Except for the matrix of 52 cases, the reports on the review, which started in February 2020, have yet to be released to the public.

Except for the matrix of 52 cases, the reports on the review, which started in February 2020, have yet to be released to the public.

Ruben Carranza, senior expert at the New York-based International Center for Transitional Justice, said there was “no effort from the Philippine government to find out if all these thousands of killings follow a pattern that might constitute crimes against humanity.”

Ruben Carranza, senior expert at the New York-based International Center for Transitional Justice, said there was “no effort from the Philippine government to find out if all these thousands of killings follow a pattern that might constitute crimes against humanity.”

Lawyers from the National Union of People’s Lawyers, who have been assisting drug war victims in seeking justice before the ICC and in domestic courts, say “very few efforts” have been made to reach out to drug-war victims and their families.

Lawyers from the National Union of People’s Lawyers, who have been assisting drug war victims in seeking justice before the ICC and in domestic courts, say “very few efforts” have been made to reach out to drug-war victims and their families.

Kristina Conti, who had just been recently accredited to appear as assistant to counsel before the ICC, said she believes Khan is ready for trial.

Kristina Conti, who had just been recently accredited to appear as assistant to counsel before the ICC, said she believes Khan is ready for trial.

“The amount of evidence before him shows, tells us this case is ripe in the sense that we have clear evidence from the victims. That the killings are widespread and systematic. And then that establishes crimes against humanity, not just murder. And he has identified a pattern, a policy that leads up to the President,” she said.

“The amount of evidence before him shows, tells us this case is ripe in the sense that we have clear evidence from the victims. That the killings are widespread and systematic. And then that establishes crimes against humanity, not just murder. And he has identified a pattern, a policy that leads up to the President,” she said.

In recent weeks prior to stepping down, Duterte appeared to distance himself from the killings.

In recent weeks prior to stepping down, Duterte appeared to distance himself from the killings.

“Yung sinasabi nila, extrajudicial killings, hindi totoo yan. Why do we have to extrajudicial kill a person? My order to law enforcement agencies is that go out and destroy the apparatus of the drug syndicate. And if you have to kill because you are in danger of being killed, go ahead, unahan mo na…Do not hesitate and I said I take full legal responsibility,” he said.

“Yung sinasabi nila, extrajudicial killings, hindi totoo yan. Why do we have to extrajudicial kill a person? My order to law enforcement agencies is that go out and destroy the apparatus of the drug syndicate. And if you have to kill because you are in danger of being killed, go ahead, unahan mo na…Do not hesitate and I said I take full legal responsibility,” he said.

But in his State of the Nation Address last year, he dared the ICC.

But in his State of the Nation Address last year, he dared the ICC.

“I never denied – and the ICC can record it – those who destroy my country, I will kill you. And those who destroy the young people of my country, I will kill you, because I love my country,” he said.

“I never denied – and the ICC can record it – those who destroy my country, I will kill you. And those who destroy the young people of my country, I will kill you, because I love my country,” he said.

That rhetoric has been a constant cause for concern to the human rights commission.

That rhetoric has been a constant cause for concern to the human rights commission.

“One of the things that we have to understand is that the President is very influential. And the words that he utters carries a lot of weight. It can be construed as policy. And what was dangerous, particularly in his enabling rhetoric over the years, was the fact that the policemen may have been listening and they may not have been able to clearly understand that there is a qualifying clause to his statement,” De Guia said.

“One of the things that we have to understand is that the President is very influential. And the words that he utters carries a lot of weight. It can be construed as policy. And what was dangerous, particularly in his enabling rhetoric over the years, was the fact that the policemen may have been listening and they may not have been able to clearly understand that there is a qualifying clause to his statement,” De Guia said.

“Nasabi niya, ‘kapag nanlaban.’ Because that is what’s allowed under the Revised Penal Code. But again, the enabling rhetoric kasi and the too much reliance that the policemen know their law and know the clear boundaries of what they have to do, was you know sufficient to encourage the approach carried out by the police,” she added.

“Nasabi niya, ‘kapag nanlaban.’ Because that is what’s allowed under the Revised Penal Code. But again, the enabling rhetoric kasi and the too much reliance that the policemen know their law and know the clear boundaries of what they have to do, was you know sufficient to encourage the approach carried out by the police,” she added.

ARE THE LIVES LOST WORTH IT?

Six years of the drug war left thousands of drug suspects killed in police operations.

Six years of the drug war left thousands of drug suspects killed in police operations.

Some of the families had to borrow money to afford a decent burial and with the lapse of their rent with the cemetery, had to find means to exhume the body and cremate them or relocate them elsewhere.

Some of the families had to borrow money to afford a decent burial and with the lapse of their rent with the cemetery, had to find means to exhume the body and cremate them or relocate them elsewhere.

The government admits the drug war was costly but has to be taken into context.

The government admits the drug war was costly but has to be taken into context.

“When you talk about 6,000 people, that’s a lot of people. So, issue talaga yan. But I guess, siguro ganito na lang. It has to be put in perspective also. We’re talking about hundreds of thousands of drug operations. Ang dami rin talaga. Ang laki rin talaga ng problema sa drugs. It’s something that I guess none of us can deny. The problem is very pervasive, it’s very widespread,” Sugay said.

“When you talk about 6,000 people, that’s a lot of people. So, issue talaga yan. But I guess, siguro ganito na lang. It has to be put in perspective also. We’re talking about hundreds of thousands of drug operations. Ang dami rin talaga. Ang laki rin talaga ng problema sa drugs. It’s something that I guess none of us can deny. The problem is very pervasive, it’s very widespread,” Sugay said.

The former Justice undersecretary said drug-related criminal complaints saw a 10-fold increase in the first 3 years of the drug war compared to figures from a decade ago.

The former Justice undersecretary said drug-related criminal complaints saw a 10-fold increase in the first 3 years of the drug war compared to figures from a decade ago.

“Marami siya talaga. So if that is any gauge, if that is any indication, I suppose it’s because the government or this [Duterte] administration really focused on fighting anti-illegal drugs,” he said.

“Marami siya talaga. So if that is any gauge, if that is any indication, I suppose it’s because the government or this [Duterte] administration really focused on fighting anti-illegal drugs,” he said.

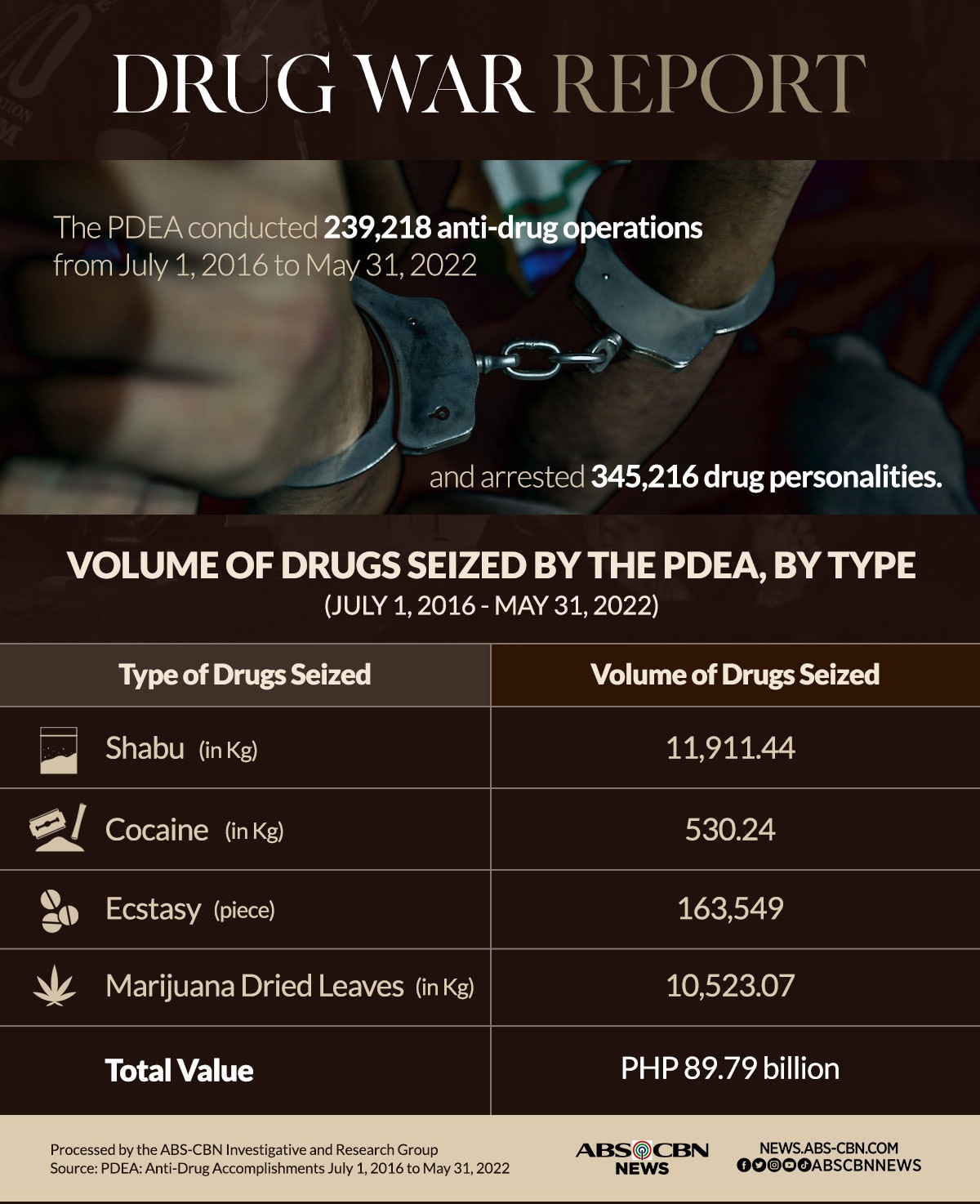

The Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) said authorities conducted more than 230,000 anti-illegal drug operations in the past 6 years which led to the arrest of more than 330,000 persons, including almost 15,000 high-value targets.

The Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) said authorities conducted more than 230,000 anti-illegal drug operations in the past 6 years which led to the arrest of more than 330,000 persons, including almost 15,000 high-value targets.

More than ten 20 tons of shabu and marijuana have been seized, amounting to 88 billion pesos worth of confiscated dangerous drugs and laboratory equipment.

More than ten 20 tons of shabu and marijuana have been seized, amounting to 88 billion pesos worth of confiscated dangerous drugs and laboratory equipment.

Almost 25,000 barangays or villages have been cleared of drugs and it claimed this has resulted in safer streets with crimes rates dropping from 45 percent in 2016 to 26 percent in April 2022.

Almost 25,000 barangays or villages have been cleared of drugs and it claimed this has resulted in safer streets with crimes rates dropping from 45 percent in 2016 to 26 percent in April 2022.

The PDEA has insisted that more lives were saved than lost in the drug war.

The PDEA has insisted that more lives were saved than lost in the drug war.

“The war on drugs is unfoundedly blamed for unlawful deaths. These... losses of lives were the result of violent actions of drug pushers towards law enforcers during lawful operations,” then-PDEA Director General Wilkins Villanueva said during the Duterte Legacy Summit in May this year. “Taking human lives was never the intent of drug war operations.”

“The war on drugs is unfoundedly blamed for unlawful deaths. These... losses of lives were the result of violent actions of drug pushers towards law enforcers during lawful operations,” then-PDEA Director General Wilkins Villanueva said during the Duterte Legacy Summit in May this year. “Taking human lives was never the intent of drug war operations.”

But the CHR said the Philippine government failed in its mission to protect and promote human rights and has in fact encouraged impunity by creating hurdles to meaningful investigations, such as blocking access to important documents.

But the CHR said the Philippine government failed in its mission to protect and promote human rights and has in fact encouraged impunity by creating hurdles to meaningful investigations, such as blocking access to important documents.

“The President himself said he had difficulty in solving the drug problem. Hindi na kaya ng six months, he himself admitted as much. And sabi nga nila, itutuloy pa rin nila sa susunod na administrasyon. And that then shows na hindi naging successful in terms of its goal to totally eradicate drugs in the country,” De Guia said.

“The President himself said he had difficulty in solving the drug problem. Hindi na kaya ng six months, he himself admitted as much. And sabi nga nila, itutuloy pa rin nila sa susunod na administrasyon. And that then shows na hindi naging successful in terms of its goal to totally eradicate drugs in the country,” De Guia said.

In Pasay City, where some of the high-profile cases like those of Eric and the Berteses took place, the drug operations over the years have led to a lower crime rate and the elimination of high-level drug trading, according to the local police chief.

In Pasay City, where some of the high-profile cases like those of Eric and the Berteses took place, the drug operations over the years have led to a lower crime rate and the elimination of high-level drug trading, according to the local police chief.

“Talagang malaki yung contributions noong drug war. So talagang nawala yung mga chronic organized crime na mga identified organized crime na nag-ooperate sa Pasay. Talagang wala ka nang makikltang malaking operations dito. Drugs puro nasa street-level operations na mostly,” said Police Colonel Cesar Paday-os, Pasay City Police Station chief of police, who took over in the midst of a pandemic last year.

“Talagang malaki yung contributions noong drug war. So talagang nawala yung mga chronic organized crime na mga identified organized crime na nag-ooperate sa Pasay. Talagang wala ka nang makikltang malaking operations dito. Drugs puro nasa street-level operations na mostly,” said Police Colonel Cesar Paday-os, Pasay City Police Station chief of police, who took over in the midst of a pandemic last year.

He said all the drug enforcement agents, some of whom were involved in alleged drug-war killings, were replaced last year.

He said all the drug enforcement agents, some of whom were involved in alleged drug-war killings, were replaced last year.

And while no high-profile drug-war killings has happened under his term, he vowed to hold accountable any of his personnel who might get involved in alleged abuses.

And while no high-profile drug-war killings has happened under his term, he vowed to hold accountable any of his personnel who might get involved in alleged abuses.

“You have to investigate talaga. Mag-iinvestigate ka. And then if it warrants na siya ay arestuhin, aarestuhin na parang normal na kriminal lalo na pag pulis, involved sa drugs, ay kailangang immediately imbestigahan. Kailangang ma-determine agad kasi di natin alam ang damage niya sa unit niya, baka chronic na na influence na ganun. Kailangang maimbestigahang mabuti lahat ng involved. Administratively and criminally, kailangan ma-charge natin,” he said.

“You have to investigate talaga. Mag-iinvestigate ka. And then if it warrants na siya ay arestuhin, aarestuhin na parang normal na kriminal lalo na pag pulis, involved sa drugs, ay kailangang immediately imbestigahan. Kailangang ma-determine agad kasi di natin alam ang damage niya sa unit niya, baka chronic na na influence na ganun. Kailangang maimbestigahang mabuti lahat ng involved. Administratively and criminally, kailangan ma-charge natin,” he said.

“You have to stick [to] what is the procedure, the PNP procedure. Yun yung bible mo. If you deviate outside that bible of PNP, yung police operations, you have no place na magstay dito sa enforcement unit ng PNP,” he added.

“You have to stick [to] what is the procedure, the PNP procedure. Yun yung bible mo. If you deviate outside that bible of PNP, yung police operations, you have no place na magstay dito sa enforcement unit ng PNP,” he added.

Meanwhile, the village chief in the barangay where Eric was killed, said the drug war has instilled fear in her constituents and have led to lesser drug incidents.

Meanwhile, the village chief in the barangay where Eric was killed, said the drug war has instilled fear in her constituents and have led to lesser drug incidents.

“At least nabawasan, natakot yung mga tao. Kung gusto man nila gumawa ng masama, dahil sa ganun, hindi na nila tinutuloy. Dahil takot na sila,” said Milagros Santos, chairperson of Barangay 43 in Pasay.

“At least nabawasan, natakot yung mga tao. Kung gusto man nila gumawa ng masama, dahil sa ganun, hindi na nila tinutuloy. Dahil takot na sila,” said Milagros Santos, chairperson of Barangay 43 in Pasay.

But she would have wanted the drug war done another way.

But she would have wanted the drug war done another way.

“Ako naman sa akin, hulihin kung talagang may kasalanan. Pero ayoko nung patayan, ayoko nun. Kunyari may kasalanan, hulihin, ikulong,” she said.

“Ako naman sa akin, hulihin kung talagang may kasalanan. Pero ayoko nung patayan, ayoko nun. Kunyari may kasalanan, hulihin, ikulong,” she said.

Alma has chosen to stay as far as possible from Pasay for now. Her one-year-old baby is now 7 years old and she said she wants to focus on raising him.

Alma has chosen to stay as far as possible from Pasay for now. Her one-year-old baby is now 7 years old and she said she wants to focus on raising him.

WHAT’S NEXT?

Duterte stepped down on June 30 leaving behind a deadly policy that left drug war victims and families desperate for justice.

Duterte stepped down on June 30 leaving behind a deadly policy that left drug war victims and families desperate for justice.

While the families of drug war victims like Hamoy and the Berteses have vowed to pursue their all the way to the ICC, Alma would rather not.

While the families of drug war victims like Hamoy and the Berteses have vowed to pursue their all the way to the ICC, Alma would rather not.

“Gusto ko na lang talaga ng tahimik. Wala na po kasi talaga akong pag-asa para sa sarili ko,” she said.

“Gusto ko na lang talaga ng tahimik. Wala na po kasi talaga akong pag-asa para sa sarili ko,” she said.

But she hopes the new administration of President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr., whom she supported, will be better for her.

But she hopes the new administration of President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr., whom she supported, will be better for her.

Former Justice Secretary and now Solicitor General Menardo Guevarra said he hopes new Justice Secretary Boying Remulla will continue the drug-war probe.

Former Justice Secretary and now Solicitor General Menardo Guevarra said he hopes new Justice Secretary Boying Remulla will continue the drug-war probe.

Guevarra will find himself defending the government’s drug war before the Supreme Court in his new role.

Guevarra will find himself defending the government’s drug war before the Supreme Court in his new role.

“Could it have been undertaken better? Wala naman kasing programa na perfect e. Marami naman talagang nagiging issues no. And when you talk about a drug war or war against drugs na as intense as it was undertaken in the last almost six years, talagang mabigat siya,” Guevarra’s former right-hand man Sugay said.

“Could it have been undertaken better? Wala naman kasing programa na perfect e. Marami naman talagang nagiging issues no. And when you talk about a drug war or war against drugs na as intense as it was undertaken in the last almost six years, talagang mabigat siya,” Guevarra’s former right-hand man Sugay said.

“I guess this is something that will have to be evaluated by the next administration, especially as they look into the anti-illegal drug war again, the anti-illegal drug war problem and see if there is really a need to reorient or redirect yung kampanya dyan,” he added.

“I guess this is something that will have to be evaluated by the next administration, especially as they look into the anti-illegal drug war again, the anti-illegal drug war problem and see if there is really a need to reorient or redirect yung kampanya dyan,” he added.

For the Commission on Human Rights, seeking justice under a new administration will require addressing the climate of fear first – looking for witnesses and reassuring them they will be protected.

For the Commission on Human Rights, seeking justice under a new administration will require addressing the climate of fear first – looking for witnesses and reassuring them they will be protected.

Case-building will also be a challenge, particularly accessing vital documents like autopsy results.

Case-building will also be a challenge, particularly accessing vital documents like autopsy results.

But De Guia stressed the importance of seeking accountability in the Philippines, even as the ICC probe continues.

But De Guia stressed the importance of seeking accountability in the Philippines, even as the ICC probe continues.

“Kaya naman natin sinusuportahan yung DOJ review panel at kaya natin sinusuportahan yung local mechanisms kasi mas mabilis ito at mas makakamit agad ng mga victims. The international mechanisms kasi will take a lot of time and it will only focus on the few highest officials — macro yung justice na makukuha — but in terms of the individual justice, napaka-importante rin sana na makuha sa local level,” she said.

“Kaya naman natin sinusuportahan yung DOJ review panel at kaya natin sinusuportahan yung local mechanisms kasi mas mabilis ito at mas makakamit agad ng mga victims. The international mechanisms kasi will take a lot of time and it will only focus on the few highest officials — macro yung justice na makukuha — but in terms of the individual justice, napaka-importante rin sana na makuha sa local level,” she said.

Despite statements by President Marcos he will not allow ICC prosecutors to enter the country and that the Philippines will not rejoin the Rome Statute that created the ICC, De Guia said there’s reason to hope.

Despite statements by President Marcos he will not allow ICC prosecutors to enter the country and that the Philippines will not rejoin the Rome Statute that created the ICC, De Guia said there’s reason to hope.

“The past few years have been challenging and has been a little bit tiring. We’re left with no room but to be cautiously optimistic and there’s reason to hope, there’s reason to be optimistic,” she said.

“The past few years have been challenging and has been a little bit tiring. We’re left with no room but to be cautiously optimistic and there’s reason to hope, there’s reason to be optimistic,” she said.

"The new president did say that he should not be judged by his ancestors but by his actions. He also met with the international community and he also met with the UN resident coordinator. And there was a commitment there, there was a recognition that human rights is important and that they are going to ensure that human rights will be protected and promoted. That holds a lot of promise and we do hope that the new administration will stay true to their word,” she added.

"The new president did say that he should not be judged by his ancestors but by his actions. He also met with the international community and he also met with the UN resident coordinator. And there was a commitment there, there was a recognition that human rights is important and that they are going to ensure that human rights will be protected and promoted. That holds a lot of promise and we do hope that the new administration will stay true to their word,” she added.

RELATED VIDEO

Read More:

Duterte drug war

extra-judicial killings

EJKs

human rights

nanlaban

peace and order

crime

criminality

Department of Justice

DOJ

ADVERTISEMENT

‘Unfulfilled deals’ may be behind Duterte’s tirades vs Marcos: political analyst

‘Unfulfilled deals’ may be behind Duterte’s tirades vs Marcos: political analyst

Joyce Balancio,

ABS-CBN News

Published Jan 29, 2024 09:14 PM PHT

|

Updated Jan 29, 2024 11:09 PM PHT

MANILA (UPDATED) — President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. might not be keeping his “end of the bargain” with the Duterte family, that is why he is receiving attacks from some members of the family, a political analyst said Monday.

Prof. Dennis Coronacion from the University of Santo Tomas Department of Political Science said the Marcoses might have sealed some deals with the Dutertes when they were convincing then Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte to be his running mate during the 2022 national elections.

MANILA (UPDATED) — President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. might not be keeping his “end of the bargain” with the Duterte family, that is why he is receiving attacks from some members of the family, a political analyst said Monday.

Prof. Dennis Coronacion from the University of Santo Tomas Department of Political Science said the Marcoses might have sealed some deals with the Dutertes when they were convincing then Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte to be his running mate during the 2022 national elections.

“Ang mga political alliances po natin, or even political parties and coalitions, they are made up of elites. And when these elites form political parties or alliance, there is definitely political arrangements or negotiations that go along with it,” Coronacion told ABS-CBN News.

“Itong rally sa Davao nitong Sunday isa ito sa paraan ng Duterte family to remind the President of, you know, what took place during the negotiations during the last presidential election," he said.

“Ang mga political alliances po natin, or even political parties and coalitions, they are made up of elites. And when these elites form political parties or alliance, there is definitely political arrangements or negotiations that go along with it,” Coronacion told ABS-CBN News.

“Itong rally sa Davao nitong Sunday isa ito sa paraan ng Duterte family to remind the President of, you know, what took place during the negotiations during the last presidential election," he said.

He said the Davao City rally may have been meant to send a "strong message" that failing to honor previous agreements or further marginalizing Vice President Sara Duterte could lead to bigger problems.

He said the Davao City rally may have been meant to send a "strong message" that failing to honor previous agreements or further marginalizing Vice President Sara Duterte could lead to bigger problems.

CONFIDENTIAL FUNDS

Coronacion explained that is possible that the Duterte family did not take it lightly when Congress removed the confidential funds of the two offices of Vice President Sara Duterte for the 2024.

Speculations that a team from the International Criminal Court had already entered the country to investigate former President Duterte’s drug war, may also have agitated the Dutertes and their supporters.

Marcos Jr.’s shooting back at the older Duterte might also be a sign that the UniTeam is “crumbling”.

“Mukhang lumalabas na napikon na rin ang Pangulo sa mga paratang sa kanya. lalo na doon sa pagkasama sa kanyang pangalan sa watchlist ng mga suspects tungkol sa illegal drugs,” he said.

Coronacion explained that is possible that the Duterte family did not take it lightly when Congress removed the confidential funds of the two offices of Vice President Sara Duterte for the 2024.

Speculations that a team from the International Criminal Court had already entered the country to investigate former President Duterte’s drug war, may also have agitated the Dutertes and their supporters.

Marcos Jr.’s shooting back at the older Duterte might also be a sign that the UniTeam is “crumbling”.

“Mukhang lumalabas na napikon na rin ang Pangulo sa mga paratang sa kanya. lalo na doon sa pagkasama sa kanyang pangalan sa watchlist ng mga suspects tungkol sa illegal drugs,” he said.

ADVERTISEMENT

“At this point parang hindi maganda ang patutunguhan kung ibabasa natin doon sa reaskyon ng pangulo. Hindi ito magandang sign para sa pagsasamahan nila,” he added.

“At this point parang hindi maganda ang patutunguhan kung ibabasa natin doon sa reaskyon ng pangulo. Hindi ito magandang sign para sa pagsasamahan nila,” he added.

'PEOPLE TO BEAR BRUNT OF FEUD'

Further he said, if the situation worsens, Vice President Duterte’s function as the concurrent education secretary will be affected.

“Iyong mapapamalakad halimbawa ni Vice President Sara Duterte sa DepEd, somehow baka maapektuhan iyon. For example, patuloy na gigipitin ang budget ng DepEd o di kaya ang opisina ng Vice President so kapag ganito na masama na ang takbo ng kanilang relasyon,” he explained.

The Alliance of Concerned Teachers (ACT) also expressed concern the passage of laws that will provide additional benefits and salary to teachers might also be compromised given the rift between the leaders of the House of Representatives and VP Duterte who is also the concurrent Education Secretary.

“Walang pakinabang dito ang mamamayang Pilipino. Iyong usapin ng sahod ngayon nakasalang lalo na usapin ng GAA 2024 at ng usapin ng salary standardization law so technically pwede makaapekto iyan,” ACT National Chairperson Vladimer Quetua said.

A youth group also lamented how the political bickering affects governance, and the giving of service to the Filipino people.

'PEOPLE TO BEAR BRUNT OF FEUD'

Further he said, if the situation worsens, Vice President Duterte’s function as the concurrent education secretary will be affected.

“Iyong mapapamalakad halimbawa ni Vice President Sara Duterte sa DepEd, somehow baka maapektuhan iyon. For example, patuloy na gigipitin ang budget ng DepEd o di kaya ang opisina ng Vice President so kapag ganito na masama na ang takbo ng kanilang relasyon,” he explained.

The Alliance of Concerned Teachers (ACT) also expressed concern the passage of laws that will provide additional benefits and salary to teachers might also be compromised given the rift between the leaders of the House of Representatives and VP Duterte who is also the concurrent Education Secretary.

“Walang pakinabang dito ang mamamayang Pilipino. Iyong usapin ng sahod ngayon nakasalang lalo na usapin ng GAA 2024 at ng usapin ng salary standardization law so technically pwede makaapekto iyan,” ACT National Chairperson Vladimer Quetua said.

A youth group also lamented how the political bickering affects governance, and the giving of service to the Filipino people.

“Nagagalit po kami dahil habang nanatiling mataas ng presyo ng bilhin, habang maliliit ang sahod ng mga manggagawa at may kinakaharap tayong krisis sa transportasyon bardagulan ang inaatupag ni Duterte at ng Marcos at basically ginagawa nila ito dahil sa pagaagawan sa kapangyarihan,” Kate Almenzo, Anakbayan’s National Spokesperson said.

“Ang talo dito sa bardagulan ng mga Marcos at Duterte ay ang mga mamamayan,” she added.

“Nagagalit po kami dahil habang nanatiling mataas ng presyo ng bilhin, habang maliliit ang sahod ng mga manggagawa at may kinakaharap tayong krisis sa transportasyon bardagulan ang inaatupag ni Duterte at ng Marcos at basically ginagawa nila ito dahil sa pagaagawan sa kapangyarihan,” Kate Almenzo, Anakbayan’s National Spokesperson said.

“Ang talo dito sa bardagulan ng mga Marcos at Duterte ay ang mga mamamayan,” she added.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT