One, two... flee: Lumad teens find refuge in Manila, pursue studies | ABS-CBN

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

One, two... flee: Lumad teens find refuge in Manila, pursue studies

One, two... flee: Lumad teens find refuge in Manila, pursue studies

Michael Joe Delizo,

ABS-CBN News

Published Mar 30, 2019 09:20 AM PHT

|

Updated Mar 30, 2019 09:59 AM PHT

MANILA – No more trembling at the sound of bombs and guns.

MANILA – No more trembling at the sound of bombs and guns.

For 70 indigenous teens who fled longstanding armed clashes in Mindanao, the torment of war has been replaced by hope as they have found refuge at the University of the Philippine in Diliman, Quezon City.

For 70 indigenous teens who fled longstanding armed clashes in Mindanao, the torment of war has been replaced by hope as they have found refuge at the University of the Philippine in Diliman, Quezon City.

In basement rooms of the UP College of Home Economics, the only sounds they hear at night are the chirping of crickets.

In basement rooms of the UP College of Home Economics, the only sounds they hear at night are the chirping of crickets.

The Lumad teens, aged between 15 and 18, have been coming in trickles since July last year for schooling, and at times they grapple with homesickness.

The Lumad teens, aged between 15 and 18, have been coming in trickles since July last year for schooling, and at times they grapple with homesickness.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Araw-araw, umiiyak pa rin ako dahil nami-miss ko ’yung magulang ko,” said Mimi, 16, from North Cotabato City.

“Araw-araw, umiiyak pa rin ako dahil nami-miss ko ’yung magulang ko,” said Mimi, 16, from North Cotabato City.

(I still cry every day because I miss my parents.)

(I still cry every day because I miss my parents.)

Since age 12, she has been a “bakwit,” slang for “evacuee,” living with interfaith leaders. Her mother, tagged as a member of the communist New People’s Army (NPA), has been in hiding for years now, contacting her only through phone.

Since age 12, she has been a “bakwit,” slang for “evacuee,” living with interfaith leaders. Her mother, tagged as a member of the communist New People’s Army (NPA), has been in hiding for years now, contacting her only through phone.

“Dati parang ayoko pumunta dito kasi malayo,” Mimi recounted. “Pero kahit naman nasa Mindanao ako, hindi ko pa rin kasama ang magulang ko.”

“Dati parang ayoko pumunta dito kasi malayo,” Mimi recounted. “Pero kahit naman nasa Mindanao ako, hindi ko pa rin kasama ang magulang ko.”

(At first, I was hesitant to go here because it is far. But I realized that even though I am in Mindanao, I am still not with my parents.)

(At first, I was hesitant to go here because it is far. But I realized that even though I am in Mindanao, I am still not with my parents.)

Manila is over 900 kilometers away from Mindanao, where insurgency, secession and banditry have been a problem for decades.

Manila is over 900 kilometers away from Mindanao, where insurgency, secession and banditry have been a problem for decades.

The region is in the cusp of a transition with the creation of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, a more empowered self-governing entity seen to end long-standing restiveness and spur greater development in the south.

The region is in the cusp of a transition with the creation of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, a more empowered self-governing entity seen to end long-standing restiveness and spur greater development in the south.

Based on a March 2019 report of child rights group Save The Children Philippines, continued hostilities in five conflict areas in Mindanao have displaced 76,383 children.

Based on a March 2019 report of child rights group Save The Children Philippines, continued hostilities in five conflict areas in Mindanao have displaced 76,383 children.

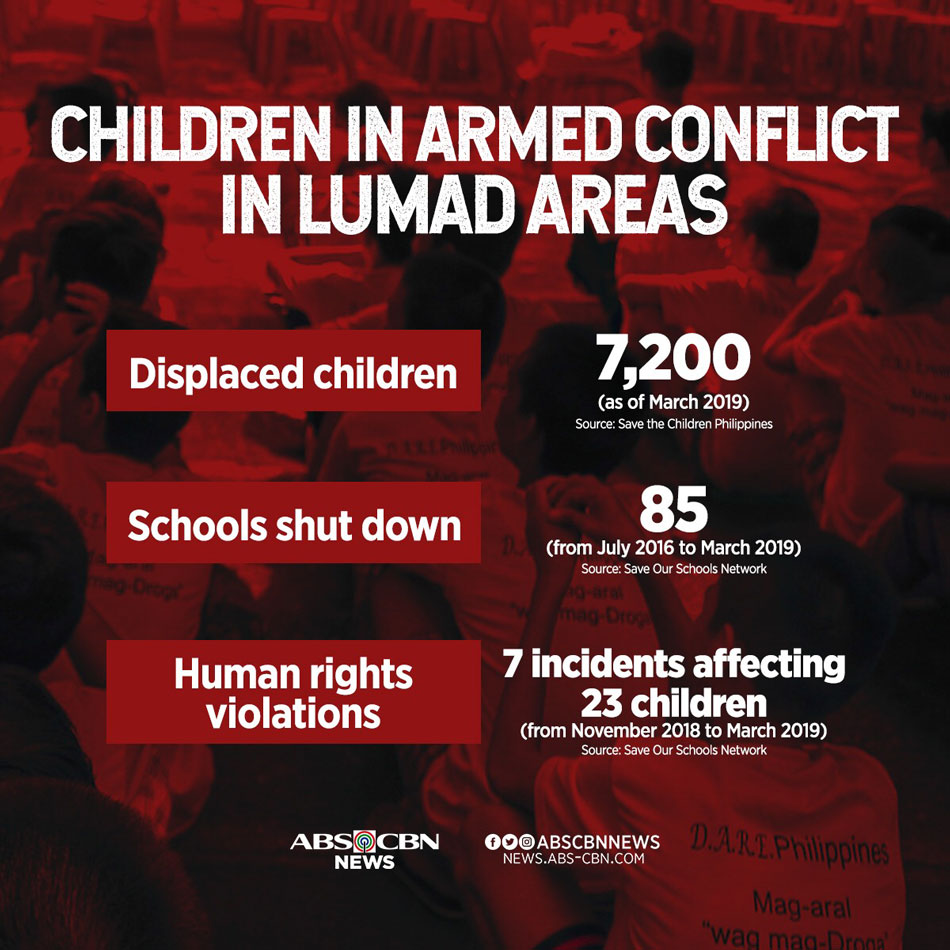

Among Lumads, about 7,200 children are out of their homes. The group of 70, Mimi among them, was brought by child-focused organization Save Our Schools (SOS) Network to UP to help them pursue studies away from the conflict.

Among Lumads, about 7,200 children are out of their homes. The group of 70, Mimi among them, was brought by child-focused organization Save Our Schools (SOS) Network to UP to help them pursue studies away from the conflict.

For many of the children, their innocence have been shattered by the sight of killings, burning of schools and gunfights, among other violent attacks.

For many of the children, their innocence have been shattered by the sight of killings, burning of schools and gunfights, among other violent attacks.

“Hindi ko makakalimutan ’yung pambabaril sa amin sa loob ng school kaya nagbunga ito nang malaking trauma sa akin,” related Norilyn from Davao del Norte.

“Hindi ko makakalimutan ’yung pambabaril sa amin sa loob ng school kaya nagbunga ito nang malaking trauma sa akin,” related Norilyn from Davao del Norte.

“Kapag naririnig ko na may kalabog kahit sa pintuan, tapos ’pag may puputok na fireworks, natatakot ako. Umiiyak na lang ako.”

“Kapag naririnig ko na may kalabog kahit sa pintuan, tapos ’pag may puputok na fireworks, natatakot ako. Umiiyak na lang ako.”

(I will not forget when we were shot at inside the school. It caused me severe trauma. Whenever I hear even a slam of a door or fireworks, I easily get afraid. I just cry.)

(I will not forget when we were shot at inside the school. It caused me severe trauma. Whenever I hear even a slam of a door or fireworks, I easily get afraid. I just cry.)

The Lumad, the collective term for Mindanao’s ethno-linguistic groups, have long been lamenting strong military presence near schools believed to be rebel-run. Some were reportedly closed, destroyed or turned into campsites.

The Lumad, the collective term for Mindanao’s ethno-linguistic groups, have long been lamenting strong military presence near schools believed to be rebel-run. Some were reportedly closed, destroyed or turned into campsites.

According to SOS Network, 85 schools have been shut down in Lumad areas since July 2016, when Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte took office. The administration has been waging offensives against communist rebels following the collapse of peace talks.

According to SOS Network, 85 schools have been shut down in Lumad areas since July 2016, when Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte took office. The administration has been waging offensives against communist rebels following the collapse of peace talks.

But sometimes, if not often, it's the indigenous people, not the rebels, who bear the brunt of the battles.

But sometimes, if not often, it's the indigenous people, not the rebels, who bear the brunt of the battles.

The SOS Network recorded seven incidents of human rights violations targeting 23 children from November 2018 to March 2019. These include cases of detention, abductions, maimings, and brutal killings supposedly perpetrated by the military due to a belief that they were NPA child warriors.

The SOS Network recorded seven incidents of human rights violations targeting 23 children from November 2018 to March 2019. These include cases of detention, abductions, maimings, and brutal killings supposedly perpetrated by the military due to a belief that they were NPA child warriors.

Growing up as a bakwit in Sultan Kudarat, Crystalyn, 16, has always felt the danger in her life after the killing of some of her relatives believed to be allied with insurgents.

Growing up as a bakwit in Sultan Kudarat, Crystalyn, 16, has always felt the danger in her life after the killing of some of her relatives believed to be allied with insurgents.

Her younger days were spent fleeing, lining up at strange evacuation sites, terrified.

Her younger days were spent fleeing, lining up at strange evacuation sites, terrified.

“Sobrang hirap maging bakwit. Hindi namin alam kung mabuhay pa kami o hindi na dahil palagi na lang andiyan ang presensya ng mga militar, kahit sa paaralan namin,” she said.

“Sobrang hirap maging bakwit. Hindi namin alam kung mabuhay pa kami o hindi na dahil palagi na lang andiyan ang presensya ng mga militar, kahit sa paaralan namin,” she said.

(It’s really hard to be a bakwit. We do not know if we will still be alive or not because soldiers are always there, even in our schools.)

(It’s really hard to be a bakwit. We do not know if we will still be alive or not because soldiers are always there, even in our schools.)

She added: “Parang pinapatay na rin nila ang mga karapatan namin dahil hindi kami makapag-aral.”

She added: “Parang pinapatay na rin nila ang mga karapatan namin dahil hindi kami makapag-aral.”

(It's as if they are also killing our rights because we cannot study.)

(It's as if they are also killing our rights because we cannot study.)

Mindanao is home to about 24 percent of the Philippines’ 107.19 million population. The island also accounts for over 40 percent of the poor, most of whom are in conflict zones where economic options are limited.

Mindanao is home to about 24 percent of the Philippines’ 107.19 million population. The island also accounts for over 40 percent of the poor, most of whom are in conflict zones where economic options are limited.

Reggie Aquino, humanitarian manager of Save the Children Philippines, has been making rounds in Mindanao to extend interventions and basic needs.

Reggie Aquino, humanitarian manager of Save the Children Philippines, has been making rounds in Mindanao to extend interventions and basic needs.

She has been exposed to what she described as horrible conditions of displaced children there. At first look, she said, it is already evident how children are extremely anxious and shorter than their age.

She has been exposed to what she described as horrible conditions of displaced children there. At first look, she said, it is already evident how children are extremely anxious and shorter than their age.

“Ang hirap ng sitwasyon ng mga bata sa Mindanao. In some areas in Mindanao, nando’n sila sa most impoverished area,” Aquino said. “Marami sa kanila ang hindi nakakapag-aral at marami ang cases ng malnutrition.”

“Ang hirap ng sitwasyon ng mga bata sa Mindanao. In some areas in Mindanao, nando’n sila sa most impoverished area,” Aquino said. “Marami sa kanila ang hindi nakakapag-aral at marami ang cases ng malnutrition.”

(The situation of children in Mindanao is really difficult. In some areas in Mindanao, they are in the most impoverished area. Most of them could not study and there are many cases of malnutrition.)

(The situation of children in Mindanao is really difficult. In some areas in Mindanao, they are in the most impoverished area. Most of them could not study and there are many cases of malnutrition.)

Lawyer Albert Muyot, chief executive officer of Save the Children Philippines, cited how children's fragile bodies and minds make them vulnerable to harm caused by armed conflict.

Lawyer Albert Muyot, chief executive officer of Save the Children Philippines, cited how children's fragile bodies and minds make them vulnerable to harm caused by armed conflict.

Thus, psychological effects and severe emotional distress last in children beyond the end of the conflict; they even lose the chance to have a future.

Thus, psychological effects and severe emotional distress last in children beyond the end of the conflict; they even lose the chance to have a future.

“The impact of conflict on children is deep, devastating and lifelong,” Muyot said.

“The impact of conflict on children is deep, devastating and lifelong,” Muyot said.

For the Lumad teens in UP, who were caught in the middle of clashes, their childhood is now but a dream.

For the Lumad teens in UP, who were caught in the middle of clashes, their childhood is now but a dream.

“Sobrang hirap siya. Nakikita ko sa ibang mga bata na naglalaro sila, sana ganon din ang maranasan namin,” said Mimi.

“Sobrang hirap siya. Nakikita ko sa ibang mga bata na naglalaro sila, sana ganon din ang maranasan namin,” said Mimi.

(It’s really hard. I see other children playing, I hope we can also experience that.)

(It’s really hard. I see other children playing, I hope we can also experience that.)

Sandra, 16, from Bukidnon, shared, “Mahirap ’pag malayo sa pamilya pero tinatatagan ko na lang ang loob ko kasi ang pag-aaral ko dito hindi lang para sa kanila kundi para sa lahat ng kabataang lumad.”

Sandra, 16, from Bukidnon, shared, “Mahirap ’pag malayo sa pamilya pero tinatatagan ko na lang ang loob ko kasi ang pag-aaral ko dito hindi lang para sa kanila kundi para sa lahat ng kabataang lumad.”

(It is difficult to be away with family but I am being strong because my schooling here is not only for them but for all the lumad children.)

(It is difficult to be away with family but I am being strong because my schooling here is not only for them but for all the lumad children.)

The Philippines has almost a complete set of legislation to protect children’s rights, not to mention its commitment to treaties relating to international humanitarian law.

The Philippines has almost a complete set of legislation to protect children’s rights, not to mention its commitment to treaties relating to international humanitarian law.

In January 2018, President Rodrigo Duterte signed into law Republic Act 11188, or the “Special Protection of Children in Situations of Armed Conflict Act,” to declare children as “zones of peace,” and should be protected from all forms of abuse and violence.

In January 2018, President Rodrigo Duterte signed into law Republic Act 11188, or the “Special Protection of Children in Situations of Armed Conflict Act,” to declare children as “zones of peace,” and should be protected from all forms of abuse and violence.

With all the supposed violations to children’s rights in Mindanao, Aquino could only hope that the new law would be observed.

With all the supposed violations to children’s rights in Mindanao, Aquino could only hope that the new law would be observed.

“Ano 'yung future na naghihintay sa kanila kung ngayon ganyan ang nangyayari sa kanila? Maraming batas na nagpo-protekta ng karapatan ng mga bata, ang problema hindi siya nai-implement nang maayos,” she stated.

“Ano 'yung future na naghihintay sa kanila kung ngayon ganyan ang nangyayari sa kanila? Maraming batas na nagpo-protekta ng karapatan ng mga bata, ang problema hindi siya nai-implement nang maayos,” she stated.

(What future awaits them if this is now happening to them? There are many laws that protect the rights of children but are not implemented properly.)

(What future awaits them if this is now happening to them? There are many laws that protect the rights of children but are not implemented properly.)

Read More:

child rights

children in armed conflict

Save the Children

Save Our Schools Network

Mindanao

Lumad

University of the Philippines

College of Home Economics

bakwit

Rodrigo Duterte

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

.jpg)