Q&A with a food historian: “We Filipinize everything. And there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that” | ABS-CBN

ADVERTISEMENT

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

Q&A with a food historian: “We Filipinize everything. And there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that”

Q&A with a food historian: “We Filipinize everything. And there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that”

Nana Ozaeta

Published Jun 23, 2019 09:01 AM PHT

|

Updated Jun 23, 2019 10:07 AM PHT

What did Filipinos eat during colonial times? What ingredients did they cook with? How did they adapt dishes that came from other shores? These are just some of the questions that Felice Prudente Sta. Maria has spent much of her career pondering and researching to come up with answers.

What did Filipinos eat during colonial times? What ingredients did they cook with? How did they adapt dishes that came from other shores? These are just some of the questions that Felice Prudente Sta. Maria has spent much of her career pondering and researching to come up with answers.

A UP graduate, writer, cultural heritage advocate, culinary historian, Sta. Maria has been at the forefront of cultural work in the Philippines since publishing her award-winning book Heirlooms and Antiques in 1980. She has headed the Metropolitan Museum of the Philippines, served as a Commissioner on the National Commission for Culture and the Arts and the UNESCO National Commission of the Philippines, and currently sits on the Ayala Museum Board of Advisors and serves as a trustee of the Philippine National Museum.

A UP graduate, writer, cultural heritage advocate, culinary historian, Sta. Maria has been at the forefront of cultural work in the Philippines since publishing her award-winning book Heirlooms and Antiques in 1980. She has headed the Metropolitan Museum of the Philippines, served as a Commissioner on the National Commission for Culture and the Arts and the UNESCO National Commission of the Philippines, and currently sits on the Ayala Museum Board of Advisors and serves as a trustee of the Philippine National Museum.

More stories on Filipino food heritage:

More stories on Filipino food heritage:

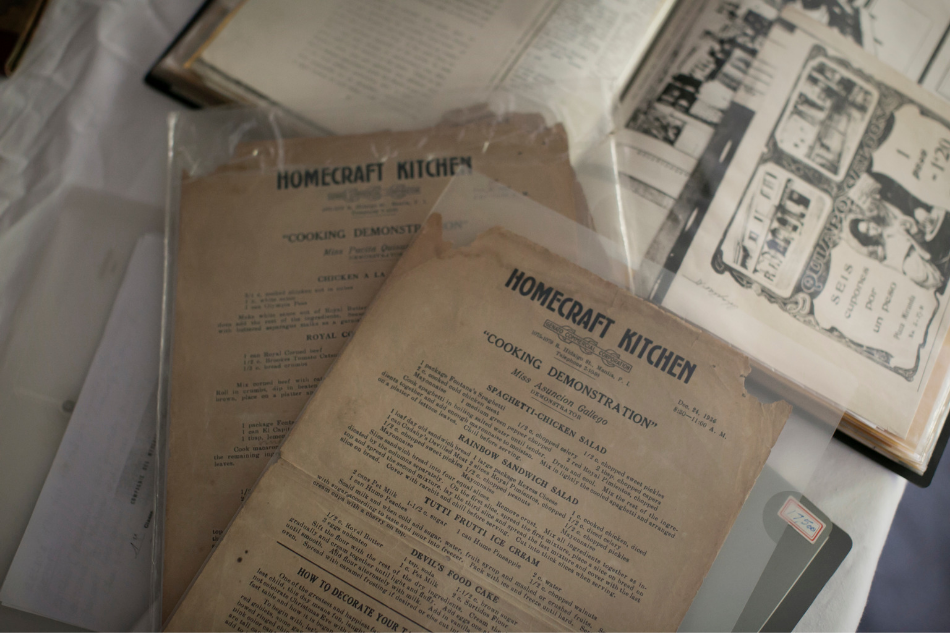

While she has written about many aspects of Philippine culture, she has been leading the way with her meticulous research on culinary history in particular. Collecting old cookbooks and recipes, pouring over colonial-era chronicles by Spanish writers, cross-checking these with government resources and statistics, Sta. Maria is adamant about properly grounding her findings with properly documented evidence.

While she has written about many aspects of Philippine culture, she has been leading the way with her meticulous research on culinary history in particular. Collecting old cookbooks and recipes, pouring over colonial-era chronicles by Spanish writers, cross-checking these with government resources and statistics, Sta. Maria is adamant about properly grounding her findings with properly documented evidence.

The results of her culinary research include award-winning books like The Governor-General’s Kitchen: Philippine Culinary Vignettes and Period Recipes, 1521-1935, The Foods of Jose Rizal, Coconut Champion: Franklin Baker Company of the Philippines (which also placed second in the Corporate History Category of Gourmand World Cook Book Awards 2017), and the list goes on.

The results of her culinary research include award-winning books like The Governor-General’s Kitchen: Philippine Culinary Vignettes and Period Recipes, 1521-1935, The Foods of Jose Rizal, Coconut Champion: Franklin Baker Company of the Philippines (which also placed second in the Corporate History Category of Gourmand World Cook Book Awards 2017), and the list goes on.

ADVERTISEMENT

For the historian Sta. Maria, research never ends, with two new books due to be published in the next few months—When Mangoes and Olives Met: A Brief Introduction to the Colonial in Philippine Cuisine, 1515-1946 and Kain Na: An Illustrated Guide to Popular Philippine Cuisine co-authored with Bryan Koh. She is also finalizing research on what will be the first lexicon of Philippine colonial-era culinary words (based on period dictionaries from 1609 to 1907), as well as Eating Our Words, a sampling of culinary terms from Spanish colonial word lists, dictionaries, and recipe books.

For the historian Sta. Maria, research never ends, with two new books due to be published in the next few months—When Mangoes and Olives Met: A Brief Introduction to the Colonial in Philippine Cuisine, 1515-1946 and Kain Na: An Illustrated Guide to Popular Philippine Cuisine co-authored with Bryan Koh. She is also finalizing research on what will be the first lexicon of Philippine colonial-era culinary words (based on period dictionaries from 1609 to 1907), as well as Eating Our Words, a sampling of culinary terms from Spanish colonial word lists, dictionaries, and recipe books.

While Sta. Maria is busy researching the past, she also keeps refreshingly current. An avid Facebook user, she serves as a judge with the Doreen Gamboa Fernandez Food Writing Awards, rewarding and cultivating writers, whether young or old, to research and write about food in the Philippine context.

While Sta. Maria is busy researching the past, she also keeps refreshingly current. An avid Facebook user, she serves as a judge with the Doreen Gamboa Fernandez Food Writing Awards, rewarding and cultivating writers, whether young or old, to research and write about food in the Philippine context.

ANCX recently visited Sta. Maria in her modernist abode in Quezon City, to listen to her inspiring words over a merienda of tsokolate using tablea from Agusan, and different kinds of biko filled with cashew butter or guava—her small yet significant way of showcasing Filipino fare at its most refined, inventive, and delicious.

ANCX recently visited Sta. Maria in her modernist abode in Quezon City, to listen to her inspiring words over a merienda of tsokolate using tablea from Agusan, and different kinds of biko filled with cashew butter or guava—her small yet significant way of showcasing Filipino fare at its most refined, inventive, and delicious.

How did you start researching about food?

How did you start researching about food?

You know the pangingue? I was given an assignment for something that I knew absolutely nothing about and I said, okay, off I go to Lopez Memorial Library, which eventually became my second home. I walked into the library, go through the card catalog, of course, there’s no entry for pangingue… The first book that I saw, the first book that I thumbed through, maybe on the third page, it was there: panguingue and it was a footnote. Maybe this was a sign that I should do this and not just women’s interest articles.

You know the pangingue? I was given an assignment for something that I knew absolutely nothing about and I said, okay, off I go to Lopez Memorial Library, which eventually became my second home. I walked into the library, go through the card catalog, of course, there’s no entry for pangingue… The first book that I saw, the first book that I thumbed through, maybe on the third page, it was there: panguingue and it was a footnote. Maybe this was a sign that I should do this and not just women’s interest articles.

What were you looking for in your research?

What were you looking for in your research?

I was a little bothered that if I saw a Spanish type dish, somebody would always say, this is cooked exactly the way my great grandmother or her mother must have done it. It bothered me. And I wanted to be able to understand how the dish I was eating got to the way it was, knowing that it was probably not like that at least a hundred years ago. And that was the search, that was how it started. And before I knew it, I was collecting recipe books when I could find them.

I was a little bothered that if I saw a Spanish type dish, somebody would always say, this is cooked exactly the way my great grandmother or her mother must have done it. It bothered me. And I wanted to be able to understand how the dish I was eating got to the way it was, knowing that it was probably not like that at least a hundred years ago. And that was the search, that was how it started. And before I knew it, I was collecting recipe books when I could find them.

What made you decide to write The Governor General’s Kitchen?

What made you decide to write The Governor General’s Kitchen?

From the 1920’s to 1935, it was a golden era. So many Philippine-written recipe books, so many articles and magazines and newspapers. It was very rich, golden era for home cooking. So I thought there was enough material to do a good book. There would be a lot of material where I was not duplicating Doreen [Gamboa Fernandez], where I was not duplicating anybody else, where the viewpoints would be a little different. I was hoping that if the book sold, that then meant we were opening up interest and maybe a buying market for books about Philippine food history.

From the 1920’s to 1935, it was a golden era. So many Philippine-written recipe books, so many articles and magazines and newspapers. It was very rich, golden era for home cooking. So I thought there was enough material to do a good book. There would be a lot of material where I was not duplicating Doreen [Gamboa Fernandez], where I was not duplicating anybody else, where the viewpoints would be a little different. I was hoping that if the book sold, that then meant we were opening up interest and maybe a buying market for books about Philippine food history.

What about your upcoming book When Mangoes and Olives Met?

What about your upcoming book When Mangoes and Olives Met?

After finishing The Governor General’s Kitchen which is everything jumbled up, little vignettes all jumbled up, I decided no, let’s try to do this into a chronology… The thing with doing this kind of chronology is, try to imagine a spine and the little bones of your spine are all about cuisine. But in order to connect the bones, you can’t just have recipes or a list of ingredients because that is not what’s going to connect them. What’s going to connect them are things like importation, weather, laws, religion, colonial policies. And so before you know it, you are unable to connect two little food thoughts without going through maybe 20, 30, 40 books just to be able to connect them, and that’s why it’s taking so long.

After finishing The Governor General’s Kitchen which is everything jumbled up, little vignettes all jumbled up, I decided no, let’s try to do this into a chronology… The thing with doing this kind of chronology is, try to imagine a spine and the little bones of your spine are all about cuisine. But in order to connect the bones, you can’t just have recipes or a list of ingredients because that is not what’s going to connect them. What’s going to connect them are things like importation, weather, laws, religion, colonial policies. And so before you know it, you are unable to connect two little food thoughts without going through maybe 20, 30, 40 books just to be able to connect them, and that’s why it’s taking so long.

What is the value of looking at food in a chronological manner?

What is the value of looking at food in a chronological manner?

Going back to my quest about how old is a Spanish dish, it helps us understand that certain dishes are not as old as we thought, maybe because the ingredients weren’t there yet. And then on the other hand, it allows us to see how one recipe changes over time, and that’s the beauty of it… You have to be able to compare government textbooks, newspaper articles, famous cooks, or famous people who taught cooking, and then have the recipes that they use side by side, one after the other, and see where the changes are. How could we cook with butter when there was no butter? When the tin butter finally arrives, what happens? And then Crisco comes in. What happens to cooking with lard, baking with lard, when you had no alternatives?

Going back to my quest about how old is a Spanish dish, it helps us understand that certain dishes are not as old as we thought, maybe because the ingredients weren’t there yet. And then on the other hand, it allows us to see how one recipe changes over time, and that’s the beauty of it… You have to be able to compare government textbooks, newspaper articles, famous cooks, or famous people who taught cooking, and then have the recipes that they use side by side, one after the other, and see where the changes are. How could we cook with butter when there was no butter? When the tin butter finally arrives, what happens? And then Crisco comes in. What happens to cooking with lard, baking with lard, when you had no alternatives?

What does your research on food tell us about being Filipino?

What does your research on food tell us about being Filipino?

At some point, it was no longer food history because I wanted to know about food; it was food history because I was curious what would I learn about the Filipino if I studied only food… People will always say, Filipinos don’t know how to make paella, it’s not Spanish. Why would you look for Spanish paella in the Philippines?…We load ours, it has so little rice and it has lots of rekado. Over there [in Spain], it’s all rice and just a little rekado. You can see what the Filipino has done to it and what we like. Don’t call it what it is not, celebrate the fact that it is a Filipinized version and make it Filipino arroz a la Valenciana or arroz Valenciana a la Filipina or something. But own it because it tastes good… We make everything Filipino, we really do. We just have not accepted that we do. I think we’re undervaluing the fact that we Filipinize always. And there is absolutely nothing wrong with putting your cultural stamp on what you believe you like and trying to keep it the best.

At some point, it was no longer food history because I wanted to know about food; it was food history because I was curious what would I learn about the Filipino if I studied only food… People will always say, Filipinos don’t know how to make paella, it’s not Spanish. Why would you look for Spanish paella in the Philippines?…We load ours, it has so little rice and it has lots of rekado. Over there [in Spain], it’s all rice and just a little rekado. You can see what the Filipino has done to it and what we like. Don’t call it what it is not, celebrate the fact that it is a Filipinized version and make it Filipino arroz a la Valenciana or arroz Valenciana a la Filipina or something. But own it because it tastes good… We make everything Filipino, we really do. We just have not accepted that we do. I think we’re undervaluing the fact that we Filipinize always. And there is absolutely nothing wrong with putting your cultural stamp on what you believe you like and trying to keep it the best.

So what do these changes in our food tell us about our culinary heritage?

So what do these changes in our food tell us about our culinary heritage?

We forget that every generation has an impact on what they think is heritage. Heritage is not static, heritage is a concept that it is stable. It helps us believe that there is stability in the culture but the interpretation is the reverse. Same thing with the cooking. We have to be open to the fact that there has to be change and food is one of the most changeable. [Food] is one of the elements of how we live that is so susceptible to change. Sometimes we don’t even realize that a food is changing, that the way somebody is cooking is changing, or that our taste buds [are changing].

We forget that every generation has an impact on what they think is heritage. Heritage is not static, heritage is a concept that it is stable. It helps us believe that there is stability in the culture but the interpretation is the reverse. Same thing with the cooking. We have to be open to the fact that there has to be change and food is one of the most changeable. [Food] is one of the elements of how we live that is so susceptible to change. Sometimes we don’t even realize that a food is changing, that the way somebody is cooking is changing, or that our taste buds [are changing].

How can food history be relevant to younger generations?

How can food history be relevant to younger generations?

On my Facebook, I have young people who are probably in their 20’s, 30’s, which is still considered quite young and I have students, so they could be in their teens for all I know, and they stick with me. So that means that the way the information is being shared with them is interesting and they like it… They are comfortable asking questions about food history. That means we are building interest in this new generation, as I had said earlier, every generation must learn its culture on its own. So as one generation is starting to fade out, one of its biggest concerns is how it can transfer to the next generation even just a little bit. Because you need some sense of continuity for a people to find strength in themselves. Food is something you can talk about all generations. It brings people together, nobody wants anybody to go hungry. Everybody wants a good meal. Everybody is excited about something new that they tasted, and everybody has an opinion, and everybody’s opinion is correct. That’s the beauty of food.

On my Facebook, I have young people who are probably in their 20’s, 30’s, which is still considered quite young and I have students, so they could be in their teens for all I know, and they stick with me. So that means that the way the information is being shared with them is interesting and they like it… They are comfortable asking questions about food history. That means we are building interest in this new generation, as I had said earlier, every generation must learn its culture on its own. So as one generation is starting to fade out, one of its biggest concerns is how it can transfer to the next generation even just a little bit. Because you need some sense of continuity for a people to find strength in themselves. Food is something you can talk about all generations. It brings people together, nobody wants anybody to go hungry. Everybody wants a good meal. Everybody is excited about something new that they tasted, and everybody has an opinion, and everybody’s opinion is correct. That’s the beauty of food.

Photos by Pat Mateo

Read More:

anc

ancx

ancx.ph

food and drink

restaurants

Felice Sta. Maria

Philippine food history

Philippine food

Filipino food

Pinoy food

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT