Revisiting old Taal through its ancestral homes and heirloom recipes | ABS-CBN

ADVERTISEMENT

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

Revisiting old Taal through its ancestral homes and heirloom recipes

Revisiting old Taal through its ancestral homes and heirloom recipes

Michaela Fenix

Published May 13, 2019 03:33 PM PHT

|

Updated May 13, 2019 03:37 PM PHT

The flags were flying high from many of the houses in Taal, revolutionary flags with the letters KKK prominently displayed. These letters, as all Filipinos should know, stand for the Kataastaasang Kagalanggalangang Katipunan of the revolutionary army. It was two days before Independence Day, and the flags were an expected sight in this heritage town, serving as colorful reminders of Taal’s illustrious residents (the ilustrado) who had risked their economic standing, and even their lives in the struggle against the Spaniards.

The flags were flying high from many of the houses in Taal, revolutionary flags with the letters KKK prominently displayed. These letters, as all Filipinos should know, stand for the Kataastaasang Kagalanggalangang Katipunan of the revolutionary army. It was two days before Independence Day, and the flags were an expected sight in this heritage town, serving as colorful reminders of Taal’s illustrious residents (the ilustrado) who had risked their economic standing, and even their lives in the struggle against the Spaniards.

Just like in many other towns in the country, many of the residents of Taal have had to leave to study or work in urban centers. The houses they left behind have deteriorated, which is a shame, because there is so much history in these homes. There is the home of Marcela Marino Agoncillo, who designed and made the Philippine flag while in exile in Hong Kong. Another house, belonging to Don Eulalio Villavicencio, was where the Katipunan leaders held their meetings—and made their escape through a trapdoor in the dining room that led to an underground tunnel, thus eluding raids by the guardia civil. The well-preserved home of the late diplomat extraordinaire Felipe Agoncillo is located at the very entrance of the town, coming from the Alitagtag route, his statue standing resplendent and formal before the gates.

Just like in many other towns in the country, many of the residents of Taal have had to leave to study or work in urban centers. The houses they left behind have deteriorated, which is a shame, because there is so much history in these homes. There is the home of Marcela Marino Agoncillo, who designed and made the Philippine flag while in exile in Hong Kong. Another house, belonging to Don Eulalio Villavicencio, was where the Katipunan leaders held their meetings—and made their escape through a trapdoor in the dining room that led to an underground tunnel, thus eluding raids by the guardia civil. The well-preserved home of the late diplomat extraordinaire Felipe Agoncillo is located at the very entrance of the town, coming from the Alitagtag route, his statue standing resplendent and formal before the gates.

You may also like:

You may also like:

Focus on restoration

Focus on restoration

My first visit to Taal 20 years ago was disappointing. Many of the houses were in a sad state of disrepair. The Basilica of St. Martin of Tours, imposing even then, built as it was on a high promontory, was unimpressive, its ceiling stripped of its painted “fresco,” which had been rolled up and stored away. Even today, few remember that the fresco had once been there.

My first visit to Taal 20 years ago was disappointing. Many of the houses were in a sad state of disrepair. The Basilica of St. Martin of Tours, imposing even then, built as it was on a high promontory, was unimpressive, its ceiling stripped of its painted “fresco,” which had been rolled up and stored away. Even today, few remember that the fresco had once been there.

What a relief to learn that in the last ten years, rehabilitation of the Basilica and the ancestral houses is being carried out. This makes Taal a must-see, especially for its history and sites for religious pilgrimage like the Basilica and the nearby Our Lady of Caysasay Shrine, known for its well of miraculous water.

What a relief to learn that in the last ten years, rehabilitation of the Basilica and the ancestral houses is being carried out. This makes Taal a must-see, especially for its history and sites for religious pilgrimage like the Basilica and the nearby Our Lady of Caysasay Shrine, known for its well of miraculous water.

ADVERTISEMENT

The great story is how Taaleños are returning to revitalize their ancestral homes, restoring them to their old glory. A prime example is the ancestral home of the Villavicencios, a gift from Don Eulalio Villavicencio to his wife, Doña Gliceria Marella y Legaspi, who had been active in the revolution. This restored mansion features antique tiles (some broken tiles have been replaced by copies), waxed and gleaming wooden planks for the flooring, hand-painted walls and carved door frames that showcase the artistry of local craftsmen. On display are the house treasures of ornate silver.

The great story is how Taaleños are returning to revitalize their ancestral homes, restoring them to their old glory. A prime example is the ancestral home of the Villavicencios, a gift from Don Eulalio Villavicencio to his wife, Doña Gliceria Marella y Legaspi, who had been active in the revolution. This restored mansion features antique tiles (some broken tiles have been replaced by copies), waxed and gleaming wooden planks for the flooring, hand-painted walls and carved door frames that showcase the artistry of local craftsmen. On display are the house treasures of ornate silver.

Sweet, familiar memories

Sweet, familiar memories

Even with all these changes taking place, the food remains the same. From my many visits to Taal, I have come to expect the dishes that first introduced me to Taal’s cuisine. This happened at the home of my first guide, Dindo Montenegro, and many of the ingredients that made up the hometown dishes were cooked in the old wood-burning stove. I remember how the late Ka Ely, Dindo’s mother, slow-cooked bulanglang using vegetables gathered from her backyard. The muslo or maliputo (jack), a prized fish from Taal Lake, was prepared two ways: the part near the head was made into sinigang and the part near the tail was charcoal-broiled.

Even with all these changes taking place, the food remains the same. From my many visits to Taal, I have come to expect the dishes that first introduced me to Taal’s cuisine. This happened at the home of my first guide, Dindo Montenegro, and many of the ingredients that made up the hometown dishes were cooked in the old wood-burning stove. I remember how the late Ka Ely, Dindo’s mother, slow-cooked bulanglang using vegetables gathered from her backyard. The muslo or maliputo (jack), a prized fish from Taal Lake, was prepared two ways: the part near the head was made into sinigang and the part near the tail was charcoal-broiled.

In the afternoon, Dindo brought me to the cockpit to taste the tinindag (pork barbecue). There were special skewers of pig ears, heart and spleen (pale), flavorful from sauce made red by achuete (annatto). The tinindag, perhaps the best of its kind in the country, can be bought daily at the market where the embers are never extinguished until late at night.

In the afternoon, Dindo brought me to the cockpit to taste the tinindag (pork barbecue). There were special skewers of pig ears, heart and spleen (pale), flavorful from sauce made red by achuete (annatto). The tinindag, perhaps the best of its kind in the country, can be bought daily at the market where the embers are never extinguished until late at night.

The town is also known for its panutsa—whole peanuts embedded in discs of hardened brown sugar. Its name can be confusing because, elsewhere in the country, panutsa or panocha refers to hardened brown sugar itself sold in half spheres.

The town is also known for its panutsa—whole peanuts embedded in discs of hardened brown sugar. Its name can be confusing because, elsewhere in the country, panutsa or panocha refers to hardened brown sugar itself sold in half spheres.

An ancestral home reawakens

An ancestral home reawakens

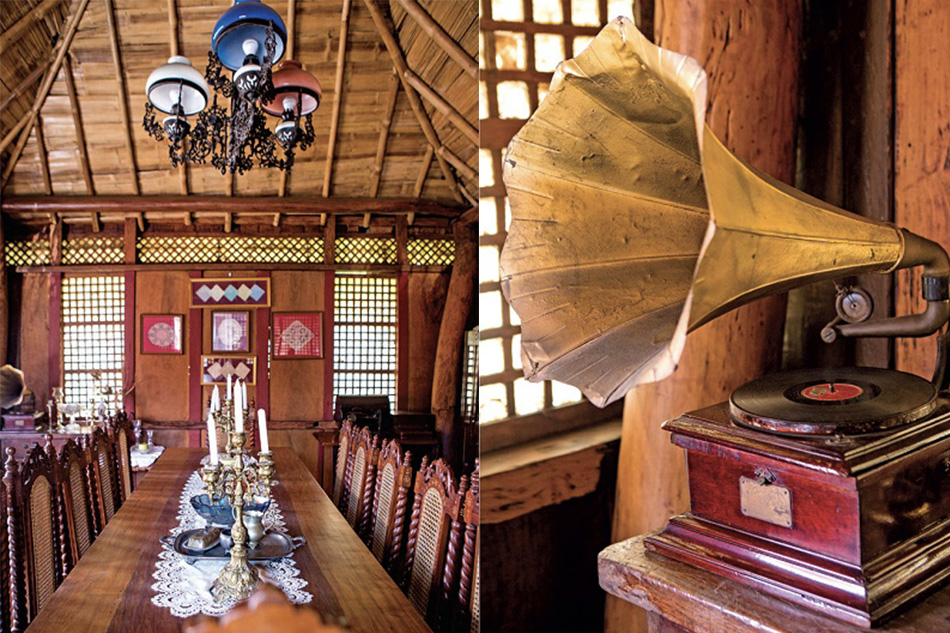

Pio Goco worked in the United States for years before deciding to come home and reopen Goco House, the ancestral home built by his great grandparents Juan Cabrera Goco and Lorenza Deomampo. The house is distinctive for its rounded corners, where the capiz windows have rounded frames, perhaps the only one of its kind in the country.

Pio Goco worked in the United States for years before deciding to come home and reopen Goco House, the ancestral home built by his great grandparents Juan Cabrera Goco and Lorenza Deomampo. The house is distinctive for its rounded corners, where the capiz windows have rounded frames, perhaps the only one of its kind in the country.

Pio is creating a bed and breakfast space soon so guests can sleep over. Right now, he offers luncheon or dinner by appointment as part of a guided tour of Taal. On a usual day trip, he’ll take you to see the spectacular view of the sunset in his town as viewed from the Basilica tower, the grim but fascinating old cemetery meant only for the Spaniards, perhaps followed by a merienda of halo-halo with feathery shaved ice made by Taal resident Jhun Estacio.

Pio is creating a bed and breakfast space soon so guests can sleep over. Right now, he offers luncheon or dinner by appointment as part of a guided tour of Taal. On a usual day trip, he’ll take you to see the spectacular view of the sunset in his town as viewed from the Basilica tower, the grim but fascinating old cemetery meant only for the Spaniards, perhaps followed by a merienda of halo-halo with feathery shaved ice made by Taal resident Jhun Estacio.

At Goco House, the table is set the way it must have been in the days when such a residence required some formality at mealtimes, with heirloom plates, crystal and silverware. The crocheted tablecloths were made by Pio’s aunts, who he says used to take care of them during their summer vacations. Among the lunch dishes served us was the quintessential Taal adobo sa dilaw, chicken braised in turmeric. Like their preference for the yellowish adobo, the Taal version of tapa is different too, being made of pork instead of beef.

At Goco House, the table is set the way it must have been in the days when such a residence required some formality at mealtimes, with heirloom plates, crystal and silverware. The crocheted tablecloths were made by Pio’s aunts, who he says used to take care of them during their summer vacations. Among the lunch dishes served us was the quintessential Taal adobo sa dilaw, chicken braised in turmeric. Like their preference for the yellowish adobo, the Taal version of tapa is different too, being made of pork instead of beef.

What a treat to taste once more the taghilaw, in which innards of pork (intestine, spleen, kidney, liver) with lean meat and brain are cooked like paksiw, boiled in vinegar, peppercorns and salt but are served dry. Pio named the soup sopas a la pobre perhaps because it was made of bulalo (beef shin) broth without the bone and its meat, but with misua (rice noodles) and speckled with malunggay (moringa) leaves. The third-generation family cook, Reggie Agoncillo, also has a way with salads and presented three versions to us, as well as two ways with kamias (bilimbi), a jam that Pio had us pair with cheese (perfect!), and a relish of pickled kamias which had just the right mix of sweet and sour and can be partnered with any fried fish.

What a treat to taste once more the taghilaw, in which innards of pork (intestine, spleen, kidney, liver) with lean meat and brain are cooked like paksiw, boiled in vinegar, peppercorns and salt but are served dry. Pio named the soup sopas a la pobre perhaps because it was made of bulalo (beef shin) broth without the bone and its meat, but with misua (rice noodles) and speckled with malunggay (moringa) leaves. The third-generation family cook, Reggie Agoncillo, also has a way with salads and presented three versions to us, as well as two ways with kamias (bilimbi), a jam that Pio had us pair with cheese (perfect!), and a relish of pickled kamias which had just the right mix of sweet and sour and can be partnered with any fried fish.

The favored fish in Taal, and in Batangas in general, is tulingan (big-eyed mackerel). It’s cut like daing (butterflied) but the two sides are brought together, pressed salt, then laid on a bed of dried kamias, steamed in low fire until the sauce called patis is expressed. Cooking it this way is known as sinaing. Agoncillo says that you’ll recognize a true Batangueño if they serve this fish fried.

The favored fish in Taal, and in Batangas in general, is tulingan (big-eyed mackerel). It’s cut like daing (butterflied) but the two sides are brought together, pressed salt, then laid on a bed of dried kamias, steamed in low fire until the sauce called patis is expressed. Cooking it this way is known as sinaing. Agoncillo says that you’ll recognize a true Batangueño if they serve this fish fried.

Like Pio, many Taaleños are now rebuilding their heritage. Lito Perez opened Villa Tortuga about 10 years ago to serve lunch, and make arrangements with local guides for a tour of the town. His main attraction is having guests pose in period costumes for their souvenir photos.

Like Pio, many Taaleños are now rebuilding their heritage. Lito Perez opened Villa Tortuga about 10 years ago to serve lunch, and make arrangements with local guides for a tour of the town. His main attraction is having guests pose in period costumes for their souvenir photos.

Traditional tavern, heritage meals

Traditional tavern, heritage meals

Chef Giney Villar closed her restaurant Adarna in Quezon City to open Feliza Taverna y Café, an old-style restaurant located in the former home of Feliza Diokno, once secretary to Emilio Aguinaldo. Many of the fixtures have been restored using original materials like bamboo, and employing Taal carpenters and craftsmen who know traditional methods. Villar also refurbished two bedrooms, making up her small B&B.

Chef Giney Villar closed her restaurant Adarna in Quezon City to open Feliza Taverna y Café, an old-style restaurant located in the former home of Feliza Diokno, once secretary to Emilio Aguinaldo. Many of the fixtures have been restored using original materials like bamboo, and employing Taal carpenters and craftsmen who know traditional methods. Villar also refurbished two bedrooms, making up her small B&B.

Giney’s version of the sinaing na tulingan deviates slightly from the traditional. She doesn’t press salt into the fish or butterfly-cut it, but keeps it whole with salt just added. Giney is known to travel around the country to learn the proper procedure for preparing heritage food. She presented other ways of serving her menu such as tapang baboy with a salad of greens and fruits, callos paired with fried eggplant in place of the berenjena (eggplant salad), and instead of gravy, the galantina (stuffed chicken) had salsa monja (Spanish sauce made of shallots, olives and torn bread pieces with olive oil) on the side.

Giney’s version of the sinaing na tulingan deviates slightly from the traditional. She doesn’t press salt into the fish or butterfly-cut it, but keeps it whole with salt just added. Giney is known to travel around the country to learn the proper procedure for preparing heritage food. She presented other ways of serving her menu such as tapang baboy with a salad of greens and fruits, callos paired with fried eggplant in place of the berenjena (eggplant salad), and instead of gravy, the galantina (stuffed chicken) had salsa monja (Spanish sauce made of shallots, olives and torn bread pieces with olive oil) on the side.

Of suman, pancit and pan de coco

Of suman, pancit and pan de coco

Walking to the market the next morning, we saw tricycles parked near Vico’s Pancit, where the vehicles’ drivers were eating breakfast from cone-shaped paper containers lined with banana leaf. The pancit was wrapped in the style of the balisungsung or cone, easy to display and to hold when eating. Some people prefer to eat this pancit with chopsticks, but plastic forks are available, too. Owner Vangie Pasumbal is also known for her tamales, a rice concoction shaped into small squares and wrapped in banana leaves. It’s a local favorite, with tangy sauce and smooth rice paste, so that supply had run out by the time we arrived—luckily we got a tip that a stall inside the market still had some.

Walking to the market the next morning, we saw tricycles parked near Vico’s Pancit, where the vehicles’ drivers were eating breakfast from cone-shaped paper containers lined with banana leaf. The pancit was wrapped in the style of the balisungsung or cone, easy to display and to hold when eating. Some people prefer to eat this pancit with chopsticks, but plastic forks are available, too. Owner Vangie Pasumbal is also known for her tamales, a rice concoction shaped into small squares and wrapped in banana leaves. It’s a local favorite, with tangy sauce and smooth rice paste, so that supply had run out by the time we arrived—luckily we got a tip that a stall inside the market still had some.

We hurried over to find a few tamales pieces left, and a lot of suman malagkit (cylindrical rice cakes). These are the best suman in town, made with sticky rice of the sungsong variety mixed with a little ordinary rice, combining the right sweetness with a semi-soft consistency, so that one tends to eat more than a piece.

We hurried over to find a few tamales pieces left, and a lot of suman malagkit (cylindrical rice cakes). These are the best suman in town, made with sticky rice of the sungsong variety mixed with a little ordinary rice, combining the right sweetness with a semi-soft consistency, so that one tends to eat more than a piece.

In a busy corner, empanada (turnovers) was being made—cooking the filling of chicken or pork or vegetables, stuffing the filling into the pastry, frying the finished empanada. Bong and Weng’s Empanada stall is also a carinderia offering cooked food and halo-halo for hungry locals and tourists alike. Weng inherited the empanada recipe from her father, added chicken and pork variety and tweaked the batter. The buyers are constant and her whole troupe also has to fill the orders for the day. The casing is firm but crisp and the filling has that well-cooked creamy chicken, beef, pork mixture.

In a busy corner, empanada (turnovers) was being made—cooking the filling of chicken or pork or vegetables, stuffing the filling into the pastry, frying the finished empanada. Bong and Weng’s Empanada stall is also a carinderia offering cooked food and halo-halo for hungry locals and tourists alike. Weng inherited the empanada recipe from her father, added chicken and pork variety and tweaked the batter. The buyers are constant and her whole troupe also has to fill the orders for the day. The casing is firm but crisp and the filling has that well-cooked creamy chicken, beef, pork mixture.

We walked round the street corner to the old bakery I had visited on an earlier trip while researching about panaderia. There was no signage, but we were told to ask for Rosenie’s Bakery. The pan de sal this bakery is known for had run out so we tried buho, what they call pan de coco (bread with a sweetened coconut filling).

We walked round the street corner to the old bakery I had visited on an earlier trip while researching about panaderia. There was no signage, but we were told to ask for Rosenie’s Bakery. The pan de sal this bakery is known for had run out so we tried buho, what they call pan de coco (bread with a sweetened coconut filling).

We left Taal late that afternoon, satisfied that we had done our rounds of ancestral homes, finished our pilgrimage and blessed ourselves with holy water from the well, slept in comfort and eaten the best food the town has to offer. Still we wondered how special Independence Day would really be in Taal given its history. For sure, the flags will fly proudly—the flag of the Katipunan and the flag of the Republic that was designed and sewn by Taaleño Marcela Marino Agoncillo.

We left Taal late that afternoon, satisfied that we had done our rounds of ancestral homes, finished our pilgrimage and blessed ourselves with holy water from the well, slept in comfort and eaten the best food the town has to offer. Still we wondered how special Independence Day would really be in Taal given its history. For sure, the flags will fly proudly—the flag of the Katipunan and the flag of the Republic that was designed and sewn by Taaleño Marcela Marino Agoncillo.

Click on the image below for slideshow

Click on the image below for slideshow

Goco Ancestral House

Marella corner Del Castillo Streets, Taal, Batangas

(0917) 373-7346

Facebook: Goco-Ancestral-House

Feliza Taverna y Café

6 Calle Felipe Agoncillo, Barangay Poblacion, Taal, Batangas

(043) 740-0113

Bong and Weng’s Empanada

Taal Public Market, (0915) 778-5825

Vico’s Pancit

39 A. de las Alas Street beside Taal Public Market,

(0908) 210-1502

Open from 4 AM to 9 AM

Villa Tortuga

Taal, Batangas, (0927) 975-1682

lito_pperez@yahoo.com

Villavincencio Wedding Gift House 32 Casa Gliceria Marella, Taal

(0920) 777-6271

Nimfa, Marie & Lestie Special Suman

Stall 289, Taal Public Market

(0920) 777-6271

Photographs by Pia Puno

This article originally appeared on Food Magazine Issue 3 2015.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT