'Sana mabigyan din ng pansin’: COVID-19 worsens struggles of families with special needs children | ABS-CBN

ADVERTISEMENT

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

'Sana mabigyan din ng pansin’: COVID-19 worsens struggles of families with special needs children

'Sana mabigyan din ng pansin’: COVID-19 worsens struggles of families with special needs children

Christina Quiambao,

ABS-CBN News

Published Dec 03, 2021 09:00 AM PHT

As soon as the rooster crows in the morning at the start of a new day in Bocaue, Bulacan, 10-year-old Red Alipao clings on to his mom Grace Donaire and spends every minute vying for her care and attention.

As soon as the rooster crows in the morning at the start of a new day in Bocaue, Bulacan, 10-year-old Red Alipao clings on to his mom Grace Donaire and spends every minute vying for her care and attention.

Being blind, deaf, and mute had made him dependent, and apparently, these physical disabilities weren’t the only obstacles he was dealing with.

Being blind, deaf, and mute had made him dependent, and apparently, these physical disabilities weren’t the only obstacles he was dealing with.

Donaire started to notice odd behaviors in her son when he was just 2 years old, frequently bumping his head on walls and profusely biting his own hands. This hasn't improved over the years and instead seemed to escalate.

Donaire started to notice odd behaviors in her son when he was just 2 years old, frequently bumping his head on walls and profusely biting his own hands. This hasn't improved over the years and instead seemed to escalate.

Looking for answers online, Donaire interacted with strangers who told her they suspect her son’s behavior was caused by a health condition that often gets overlooked.

Looking for answers online, Donaire interacted with strangers who told her they suspect her son’s behavior was caused by a health condition that often gets overlooked.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Pina-check-up nila sa developmental pedia, sa neuro tsaka sa psychiatrist. Sa kanila po galing ‘yung mga perang binigay,” Donaire said, referring to strangers who donated money to get her son checked.

“Pina-check-up nila sa developmental pedia, sa neuro tsaka sa psychiatrist. Sa kanila po galing ‘yung mga perang binigay,” Donaire said, referring to strangers who donated money to get her son checked.

(They had him checked-up with a developmental pediatrician, a neurologist, and a psychiatrist. The money came from them.)

(They had him checked-up with a developmental pediatrician, a neurologist, and a psychiatrist. The money came from them.)

After numerous tests and check-ups by several specialists, she found out why her son was acting odd: autism spectrum disorder, generalized tonic epilepsy, and global developmental delay.

After numerous tests and check-ups by several specialists, she found out why her son was acting odd: autism spectrum disorder, generalized tonic epilepsy, and global developmental delay.

The diagnosis came like a double-edged sword: she felt relieved finally knowing the root of her son’s struggles of more than six years being left undiagnosed, but it also brought the realization that he would need more health care support than ever— support that she’s unsure if their family could afford.

The diagnosis came like a double-edged sword: she felt relieved finally knowing the root of her son’s struggles of more than six years being left undiagnosed, but it also brought the realization that he would need more health care support than ever— support that she’s unsure if their family could afford.

Their story is just one among millions of persons with disabilities (PWDs) who continue to struggle and even face worse conditions due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Their story is just one among millions of persons with disabilities (PWDs) who continue to struggle and even face worse conditions due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

ADVERTISEMENT

In the Philippines, these conditions are often underreported and under-prioritized.

In the Philippines, these conditions are often underreported and under-prioritized.

The Philippine census on population and housing show a significant increase in PWDs over the years: 919,290 in 1995; 942,090 in 2000; and 1.44 million in 2010. However, much has yet to be known how high this number has gone in the 11 years that has passed since the last count.

The Philippine census on population and housing show a significant increase in PWDs over the years: 919,290 in 1995; 942,090 in 2000; and 1.44 million in 2010. However, much has yet to be known how high this number has gone in the 11 years that has passed since the last count.

Emerito Rojas, Executive Director of the National Council on Disability Affairs (NCDA), and also a PWD after losing his voice in 2002 due to laryngeal cancer, said this outdated statistic on the population of PWDs in the country.

Emerito Rojas, Executive Director of the National Council on Disability Affairs (NCDA), and also a PWD after losing his voice in 2002 due to laryngeal cancer, said this outdated statistic on the population of PWDs in the country.

“There are so many challenges. For example, internet connection, lack of compatibility of databases, mabagal na transmission, and so many more.”

“There are so many challenges. For example, internet connection, lack of compatibility of databases, mabagal na transmission, and so many more.”

He said NCDA is currently in collaboration with other organizations and institutions to update this data, projecting that by December 2022 they would have 2 million PWDs encoded in their database.

He said NCDA is currently in collaboration with other organizations and institutions to update this data, projecting that by December 2022 they would have 2 million PWDs encoded in their database.

ADVERTISEMENT

As the data continues to be in progress in the country’s top agency for PWDs, lack of an accurate benchmark on their population could lead to inadequate support on their basic necessities and health care services.

As the data continues to be in progress in the country’s top agency for PWDs, lack of an accurate benchmark on their population could lead to inadequate support on their basic necessities and health care services.

The lack of early detection and adequate health care could have a grave impact on the development of a child with disability, said Dipak Natali, Regional President and Managing Director of Special Olympics - Asia Pacific.

The lack of early detection and adequate health care could have a grave impact on the development of a child with disability, said Dipak Natali, Regional President and Managing Director of Special Olympics - Asia Pacific.

“If you don't actually look to support a child in those early stages of development, their ability to learn, their cognitive development and their physical development will be later affected,” he explained.

“If you don't actually look to support a child in those early stages of development, their ability to learn, their cognitive development and their physical development will be later affected,” he explained.

For parents with special needs children who are living from pay check to pay check, support for these needs is often difficult to attain.

For parents with special needs children who are living from pay check to pay check, support for these needs is often difficult to attain.

The costs of health care in the Philippines

Persons with disabilities come in all types: mental health conditions, vision impairments, hard of hearing or deaf, acquired brain injury, autism spectrum disorder, and/or physical and intellectual disabilities.

Persons with disabilities come in all types: mental health conditions, vision impairments, hard of hearing or deaf, acquired brain injury, autism spectrum disorder, and/or physical and intellectual disabilities.

ADVERTISEMENT

Therapy for the intellectually and developmentally disabled vary depending on the need of the child, whether it's speech, occupational, and/or physical disability. In one session it could cost up to P1,250 per hour, according to Bright Minds PH, a speech and occupational therapy center in the Philippines.

Therapy for the intellectually and developmentally disabled vary depending on the need of the child, whether it's speech, occupational, and/or physical disability. In one session it could cost up to P1,250 per hour, according to Bright Minds PH, a speech and occupational therapy center in the Philippines.

For Donaire’s son who has at least four types of disabilities, prescription medications and medical check-ups cost thousands of pesos— an overwhelming cost for the family.

For Donaire’s son who has at least four types of disabilities, prescription medications and medical check-ups cost thousands of pesos— an overwhelming cost for the family.

Her partner’s measly salary as a barangay tanod is just enough for their household's monthly expenses and before the COVID-19 pandemic, her income as a plasticware vendor in Divisoria and a fish ball vendor in their town used to help cover the costs of her son’s maintenance medications.

Her partner’s measly salary as a barangay tanod is just enough for their household's monthly expenses and before the COVID-19 pandemic, her income as a plasticware vendor in Divisoria and a fish ball vendor in their town used to help cover the costs of her son’s maintenance medications.

When lockdowns were enforced last year, she lost her additional income as vendor. Her health also started to deteriorate due to stress and exhaustion.

When lockdowns were enforced last year, she lost her additional income as vendor. Her health also started to deteriorate due to stress and exhaustion.

“Huminto ako eh... marami na akong nararamdaman,” Donaire shared.

“Huminto ako eh... marami na akong nararamdaman,” Donaire shared.

ADVERTISEMENT

(I stopped. I was already feeling a lot of aches.)

(I stopped. I was already feeling a lot of aches.)

Despite her hustle in online selling as substitute for lost income, it was still not enough to cover the cost of her son’s therapy sessions and their transportation fees going to public hospitals.

Despite her hustle in online selling as substitute for lost income, it was still not enough to cover the cost of her son’s therapy sessions and their transportation fees going to public hospitals.

Bon Cordova, a father of three who works as a nightshift janitor, bares similar sentiments with Donaire as he himself said that they lacked opportunities to send his 3-year-old daughter Hinley to therapy after she was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder last year.

Bon Cordova, a father of three who works as a nightshift janitor, bares similar sentiments with Donaire as he himself said that they lacked opportunities to send his 3-year-old daughter Hinley to therapy after she was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder last year.

“Mahal po kasi ‘yung doktor sa ganyang therapy po tapos wala rin pong check-up kasi po iba... therapist po ‘yung titingin sa mga ganito,” he explained.

“Mahal po kasi ‘yung doktor sa ganyang therapy po tapos wala rin pong check-up kasi po iba... therapist po ‘yung titingin sa mga ganito,” he explained.

(It was because the doctor’s fee for the therapy was expensive and then I didn’t have her checked-up because what she needed was different... she needed a therapist to look into this.)

(It was because the doctor’s fee for the therapy was expensive and then I didn’t have her checked-up because what she needed was different... she needed a therapist to look into this.)

ADVERTISEMENT

Both Cordova and his wife are janitors, substituting each other's shifts at work and in home care. Their monthly salary is also just enough to provide for their family of five, with their youngest still just a year old.

Both Cordova and his wife are janitors, substituting each other's shifts at work and in home care. Their monthly salary is also just enough to provide for their family of five, with their youngest still just a year old.

Beyond trying to provide for his daughter’s medical needs, it’s still an uphill battle their family has yet to come into terms with, he said.

Beyond trying to provide for his daughter’s medical needs, it’s still an uphill battle their family has yet to come into terms with, he said.

“Hindi mo alam kung nagugutom sila, kung anong gusto niya... Hindi po kasi namin alam ‘yung nararamdaman nila kaya ‘yun ‘yung mahirap,” he added.

“Hindi mo alam kung nagugutom sila, kung anong gusto niya... Hindi po kasi namin alam ‘yung nararamdaman nila kaya ‘yun ‘yung mahirap,” he added.

(You don’t know if they’re hungry or what they want. We don’t know how they feel and that’s what makes it difficult.)

(You don’t know if they’re hungry or what they want. We don’t know how they feel and that’s what makes it difficult.)

Lack of access to health care services is a prominent problem among families with low monthly household income despite existing government benefits and discounts for PWDs.

Section 20 of Republic Act 7277 states that “the State shall protect and promote the right to health of disabled persons and shall adopt an integrated and comprehensive approach to their health development which shall make essential health services available to them at affordable cost.”

Lack of access to health care services is a prominent problem among families with low monthly household income despite existing government benefits and discounts for PWDs.

Section 20 of Republic Act 7277 states that “the State shall protect and promote the right to health of disabled persons and shall adopt an integrated and comprehensive approach to their health development which shall make essential health services available to them at affordable cost.”

ADVERTISEMENT

In Section 4 of the Implementing Rules and Regulations of Republic Act 10754, meanwhile, PWDs are granted “at least 20 percent discount and exemption from the value added tax on the sale of certain goods and services for their exclusive use, enjoyment or availment.”

In Section 4 of the Implementing Rules and Regulations of Republic Act 10754, meanwhile, PWDs are granted “at least 20 percent discount and exemption from the value added tax on the sale of certain goods and services for their exclusive use, enjoyment or availment.”

Although these existing laws aim to support the basic and health care needs of PWDs, applying and processing for such support and services remain competitive and insufficient, leaving no room for parents to take the opportunity and avail them.

Although these existing laws aim to support the basic and health care needs of PWDs, applying and processing for such support and services remain competitive and insufficient, leaving no room for parents to take the opportunity and avail them.

As finances remain to be one of the biggest factors why special needs children become underdeveloped and highly-dependent, Ivory Santos says it is still just one of the several issues that need to be looked into to understand these families’ struggles.

As finances remain to be one of the biggest factors why special needs children become underdeveloped and highly-dependent, Ivory Santos says it is still just one of the several issues that need to be looked into to understand these families’ struggles.

Living in San Pedro, Laguna, Santos shared difficulties of accessing health care services as her son Gabriel, an 11-year-old child with cerebral palsy, gets his check-ups and therapy sessions at the Philippine Children's Medical Center (PCMC) in Quezon City.

Living in San Pedro, Laguna, Santos shared difficulties of accessing health care services as her son Gabriel, an 11-year-old child with cerebral palsy, gets his check-ups and therapy sessions at the Philippine Children's Medical Center (PCMC) in Quezon City.

“Not all can easily access papuntang PCMC so [ito] ang nagiging struggle namin. Kung doon kami pupunta doon sa area namin, whether dun sa ospital or clinic, ang laging sasabihin sa'min, walang kwarto or walang doktor, or hindi pwede 'yung anak,” she said.

“Not all can easily access papuntang PCMC so [ito] ang nagiging struggle namin. Kung doon kami pupunta doon sa area namin, whether dun sa ospital or clinic, ang laging sasabihin sa'min, walang kwarto or walang doktor, or hindi pwede 'yung anak,” she said.

ADVERTISEMENT

(Not all can easily access going to PCMC and so, this becomes our struggle. If we were to go to those within our area, whether it’s in a hospital or a clinic, they would always say to us that there were no more rooms or doctors or our child was not allowed.)

(Not all can easily access going to PCMC and so, this becomes our struggle. If we were to go to those within our area, whether it’s in a hospital or a clinic, they would always say to us that there were no more rooms or doctors or our child was not allowed.)

Both private and public hospitals in the nearly two years of the COVID-19 pandemic would sometimes close its doors to non-COVID patients to better manage the surge in coronavirus cases.

Both private and public hospitals in the nearly two years of the COVID-19 pandemic would sometimes close its doors to non-COVID patients to better manage the surge in coronavirus cases.

To address this issue, health care institutions shifted to the online space, providing virtual consultations and therapy sessions for PWDs so they could stay at home and safe from the infectious disease.

To address this issue, health care institutions shifted to the online space, providing virtual consultations and therapy sessions for PWDs so they could stay at home and safe from the infectious disease.

“We piloted that about a couple of months ago since August and medyo successful naman po. We have also deployed tablets kasi ‘yung iba cellphone lang ang gamit... hopefully naiibsan natin. At least unti-unti nating napapakita ‘yung bench model on how to conduct or support ‘yung mga children with disabilities during the pandemic,” Rojas said.

“We piloted that about a couple of months ago since August and medyo successful naman po. We have also deployed tablets kasi ‘yung iba cellphone lang ang gamit... hopefully naiibsan natin. At least unti-unti nating napapakita ‘yung bench model on how to conduct or support ‘yung mga children with disabilities during the pandemic,” Rojas said.

Telemedicine may have provided a short-term solution to the problem in accessing health care services in the time of COVID-19 but for some parents, they say it’s still not enough.

Telemedicine may have provided a short-term solution to the problem in accessing health care services in the time of COVID-19 but for some parents, they say it’s still not enough.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Kaya lang [‘yung] teleconsult, mabigat din sa bulsa. May kamahalan siya kaysa sa regular na face-to-face na setup. So 'yun ‘yung isang part ng struggle mo when it comes to cost. So, if mag-offer ng teleconsult, sana kung mabibigyan ng way lalo na para sa ganitong mga bata. Sana mabigyan din ng konting consideration kasi not all parents kaya ang cost ng teleconsult,” Santos said.

“Kaya lang [‘yung] teleconsult, mabigat din sa bulsa. May kamahalan siya kaysa sa regular na face-to-face na setup. So 'yun ‘yung isang part ng struggle mo when it comes to cost. So, if mag-offer ng teleconsult, sana kung mabibigyan ng way lalo na para sa ganitong mga bata. Sana mabigyan din ng konting consideration kasi not all parents kaya ang cost ng teleconsult,” Santos said.

As PWDs remain to be at a higher risk from the infectious disease due to weakened immunity, the three children are until now unqualified to receive their COVID-19 vaccination shots as they are all under the age of 12.

As PWDs remain to be at a higher risk from the infectious disease due to weakened immunity, the three children are until now unqualified to receive their COVID-19 vaccination shots as they are all under the age of 12.

More research is on-going to determine if existing vaccines are safe for children within their age bracket and other countries have just started vaccinating minors.

More research is on-going to determine if existing vaccines are safe for children within their age bracket and other countries have just started vaccinating minors.

The Philippines recently started vaccinating minors aged 12 to 17.

The Philippines recently started vaccinating minors aged 12 to 17.

But for children with special needs still in the age below the allowed bracket, the only option left is to follow basic COVID-19 protocols, with staying at home as the best option.

But for children with special needs still in the age below the allowed bracket, the only option left is to follow basic COVID-19 protocols, with staying at home as the best option.

ADVERTISEMENT

Grave effects of isolation on development

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the overall development of children with disabilities.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the overall development of children with disabilities.

Melanie Lim, among founders of CP Cares PH, shared that the interrupted routine of her son Quartz, who has cerebral palsy, due to the pandemic affected his progress in socializing with other people.

Melanie Lim, among founders of CP Cares PH, shared that the interrupted routine of her son Quartz, who has cerebral palsy, due to the pandemic affected his progress in socializing with other people.

Their usual weekly routine included going to the mall after his therapy sessions, a luxury they could no longer afford because of the coronavirus.

Their usual weekly routine included going to the mall after his therapy sessions, a luxury they could no longer afford because of the coronavirus.

“Hindi ko masasabing aloof na siya sa tao pero siguro nag-aadjust na naman ‘yung katawan niya kapag may mga taong darating or may makakasalimuha siyang bago or mga dating kakilala na niya,” she said.

“Hindi ko masasabing aloof na siya sa tao pero siguro nag-aadjust na naman ‘yung katawan niya kapag may mga taong darating or may makakasalimuha siyang bago or mga dating kakilala na niya,” she said.

(I can’t say that he became aloof as a person but I guess he’s adjusting again whenever someone new approaches or someone he used to know approaches him.)

(I can’t say that he became aloof as a person but I guess he’s adjusting again whenever someone new approaches or someone he used to know approaches him.)

ADVERTISEMENT

She added that her 8-year-old son used to be nonchalant when it came to strangers and was often open to welcome them if they wanted to meet and talk to him.

She added that her 8-year-old son used to be nonchalant when it came to strangers and was often open to welcome them if they wanted to meet and talk to him.

As quarantine restrictions became tighter and the spread of COVID-19 infections became riskier, her son regressed in the area of social interactions.

As quarantine restrictions became tighter and the spread of COVID-19 infections became riskier, her son regressed in the area of social interactions.

Lim said she often feels as if she needs to constantly bargain with her son on whether or not he could go outside during his moments of frustration.

Lim said she often feels as if she needs to constantly bargain with her son on whether or not he could go outside during his moments of frustration.

“Minsan sigaw sigaw siya ng konti, tapos mamaya luluhod na siya para sabihing ‘itayo mo na ako, lalabas mo na ako,’” she added.

“Minsan sigaw sigaw siya ng konti, tapos mamaya luluhod na siya para sabihing ‘itayo mo na ako, lalabas mo na ako,’” she added.

(Sometimes he would scream and then later he would kneel and tell me “Help me stand up, I want to go outside.”)

(Sometimes he would scream and then later he would kneel and tell me “Help me stand up, I want to go outside.”)

ADVERTISEMENT

It was a sentiment that is all too familiar for Donaire as she recalled how her son expresses his irritation over the isolation due to the pandemic.

It was a sentiment that is all too familiar for Donaire as she recalled how her son expresses his irritation over the isolation due to the pandemic.

“Kinakagat niya po ‘yung sarili niya. Pinapalo niya [sarili niya] tapos umiiyak siya na parang nanlilisik ‘yung mata,” she shared in a worried tone.

“Kinakagat niya po ‘yung sarili niya. Pinapalo niya [sarili niya] tapos umiiyak siya na parang nanlilisik ‘yung mata,” she shared in a worried tone.

(He would bite himself. He would hit himself then cry so much as his eyes would glare.)

(He would bite himself. He would hit himself then cry so much as his eyes would glare.)

Donaire said she tries to soothe him by giving him unfamiliar objects to touch and play with, a technique she learned after having struggled for years to communicate with her blind, deaf, mute and developmentally challenged son.

Donaire said she tries to soothe him by giving him unfamiliar objects to touch and play with, a technique she learned after having struggled for years to communicate with her blind, deaf, mute and developmentally challenged son.

For Santos, reasoning and communicating with her child is a little bit easier as he is consistently vocal about his needs and wants.

For Santos, reasoning and communicating with her child is a little bit easier as he is consistently vocal about his needs and wants.

ADVERTISEMENT

However, she shares that it still causes her heartache whenever he asks her to go out.

However, she shares that it still causes her heartache whenever he asks her to go out.

“Minsan sasabihin niya 'mommy punta tayo sa mall'... ngayon ang gusto niya naman... is going to the cemetery,” she said.

“Minsan sasabihin niya 'mommy punta tayo sa mall'... ngayon ang gusto niya naman... is going to the cemetery,” she said.

(Sometimes he would say 'mommy, let’s go to the mall.' Now, what he wants is going to the cemetery.)

(Sometimes he would say 'mommy, let’s go to the mall.' Now, what he wants is going to the cemetery.)

Her husband Ramil Santos died this year on Father’s Day due to Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor (GIST), a cancer of the soft tissue. And her son wants to visit his dad often.

Her husband Ramil Santos died this year on Father’s Day due to Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor (GIST), a cancer of the soft tissue. And her son wants to visit his dad often.

“Ang sasabihin niya ‘pasyal ako kay daddy, pasyal ako kay lola,’ Andoon sa point na araw-araw na ‘yon so nakikita ko sa kanya na gusto niya lumabas,” she added.

“Ang sasabihin niya ‘pasyal ako kay daddy, pasyal ako kay lola,’ Andoon sa point na araw-araw na ‘yon so nakikita ko sa kanya na gusto niya lumabas,” she added.

ADVERTISEMENT

(What he would say is 'I want to go see daddy; I want to go see grandma.' It came to the point that every day, I see him longing to go outside.)

(What he would say is 'I want to go see daddy; I want to go see grandma.' It came to the point that every day, I see him longing to go outside.)

She said her son also wished to go back to school to meet his friends and classmates after more than a year of being pulled out from the program.

She said her son also wished to go back to school to meet his friends and classmates after more than a year of being pulled out from the program.

“Sinabihan din kami ng school na they cannot accommodate that [many] students. It’s a SPED school, ang kaya lang naman nila i-accommodate na SPED is ‘yung may mobility, ‘yung they can go out na talaga and medyo adult na rin pero ‘yung kagaya sa age ni Gab, hindi na,” Santos said.

“Sinabihan din kami ng school na they cannot accommodate that [many] students. It’s a SPED school, ang kaya lang naman nila i-accommodate na SPED is ‘yung may mobility, ‘yung they can go out na talaga and medyo adult na rin pero ‘yung kagaya sa age ni Gab, hindi na,” Santos said.

(The school told us that they cannot accommodate that many students. It’s a SPED school and they said they can only accommodate those that have mobility and those that can already go out, somewhat of an adult already and not like those similar to Gab’s age.)

(The school told us that they cannot accommodate that many students. It’s a SPED school and they said they can only accommodate those that have mobility and those that can already go out, somewhat of an adult already and not like those similar to Gab’s age.)

The mothers said the lack of physical interaction, familiarization with social cues, and limited access to mobility gravely caused aggression among their children and regressions in their development.

Despite the recent ease in restrictions and amid the threat of the new Omicron variant, children still lack the immunity to protect themselves from the virus. Rojas said the effects of isolation on children with disabilities should be more closely watched.

The mothers said the lack of physical interaction, familiarization with social cues, and limited access to mobility gravely caused aggression among their children and regressions in their development.

Despite the recent ease in restrictions and amid the threat of the new Omicron variant, children still lack the immunity to protect themselves from the virus. Rojas said the effects of isolation on children with disabilities should be more closely watched.

ADVERTISEMENT

He said the long-term negative effects of having children with special needs cooped up in their homes for long periods could help institutions and organizations for PWDs create programs or find solutions on how to address them even in the post-pandemic setting.

He said the long-term negative effects of having children with special needs cooped up in their homes for long periods could help institutions and organizations for PWDs create programs or find solutions on how to address them even in the post-pandemic setting.

Exacerbation of stigma and discrimination

In the pandemic where the line between life and death is mostly drawn by health care institutions, special needs children also receive the short end of the stick on being treated fairly and justly.

In the pandemic where the line between life and death is mostly drawn by health care institutions, special needs children also receive the short end of the stick on being treated fairly and justly.

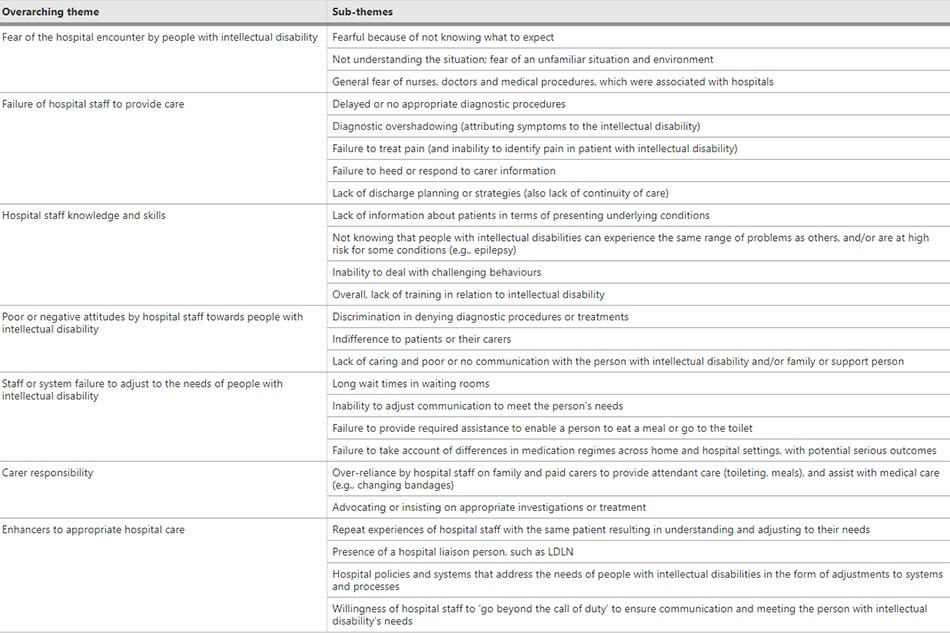

Studies in numerous countries have documented that people with intellectual and developmental disabilities are particularly likely to experience poor treatment, including discrimination and mismanagement in health settings.

Studies in numerous countries have documented that people with intellectual and developmental disabilities are particularly likely to experience poor treatment, including discrimination and mismanagement in health settings.

BMC Health Services Research, a peer-reviewed journal, published a report in 2014 that says despite 20 years of research and government initiatives, people with intellectual disabilities continue to have poor hospital experiences.

BMC Health Services Research, a peer-reviewed journal, published a report in 2014 that says despite 20 years of research and government initiatives, people with intellectual disabilities continue to have poor hospital experiences.

The same report showed that the failures of hospitals and staff to meet patient needs appeared to have arisen from limited knowledge and skills of staff as well as negative attitudes, resulting in the reliance on carers for both care and advocacy for appropriate treatment.

The same report showed that the failures of hospitals and staff to meet patient needs appeared to have arisen from limited knowledge and skills of staff as well as negative attitudes, resulting in the reliance on carers for both care and advocacy for appropriate treatment.

ADVERTISEMENT

In the Philippines, such treatment was both witnessed and experienced by Santos in her hospital visits with her child. Sharing prior experience with health professionals who were taking care of her son, she said that their way of communication could sometimes come off as discriminating.

In the Philippines, such treatment was both witnessed and experienced by Santos in her hospital visits with her child. Sharing prior experience with health professionals who were taking care of her son, she said that their way of communication could sometimes come off as discriminating.

“The way na kausapin pa ako ng doktor parang added to my... psychological [distress] naming mga magulang. Instead na makalma kami kasi andito kami sa ospital, minsan hindi namin alam at that time kung dahil lang sa sitwasyon o toxic na mga doktor,” she added.

“The way na kausapin pa ako ng doktor parang added to my... psychological [distress] naming mga magulang. Instead na makalma kami kasi andito kami sa ospital, minsan hindi namin alam at that time kung dahil lang sa sitwasyon o toxic na mga doktor,” she added.

(The way the doctor would talk to me added to my... psychological distress as a parent. Instead of being calm at the fact that we were already in the hospital, sometimes you just don’t know whether if it’s the situation or it’s the doctors that are becoming toxic.)

(The way the doctor would talk to me added to my... psychological distress as a parent. Instead of being calm at the fact that we were already in the hospital, sometimes you just don’t know whether if it’s the situation or it’s the doctors that are becoming toxic.)

Natali echoes the report’s findings, saying poor treatment from health care providers to people with intellectual and developmental disabilities can be attributed to minimal training.

Natali echoes the report’s findings, saying poor treatment from health care providers to people with intellectual and developmental disabilities can be attributed to minimal training.

“What we're dealing with here is a community that is so marginalized and faces so much social stigma that people are embarrassed to talk about it,” he explained.

“What we're dealing with here is a community that is so marginalized and faces so much social stigma that people are embarrassed to talk about it,” he explained.

ADVERTISEMENT

In 2015, another report from BMC Health Services Research identifying sexual and reproductive health services for women with disability in the Philippines showed that “service providers’ attempts to avoid offending or disempowering people with disability through inappropriate language revealed their uneasiness and confusion when talking about disability.”

In 2015, another report from BMC Health Services Research identifying sexual and reproductive health services for women with disability in the Philippines showed that “service providers’ attempts to avoid offending or disempowering people with disability through inappropriate language revealed their uneasiness and confusion when talking about disability.”

It also found that “service providers had limited training in how to meet the needs of women with disability, or held negative attitudes towards them, that clinicians could be uncomfortable treating women with disability and behave inappropriately.”

It also found that “service providers had limited training in how to meet the needs of women with disability, or held negative attitudes towards them, that clinicians could be uncomfortable treating women with disability and behave inappropriately.”

Natali said the COVID-19 pandemic also led to the exacerbation of stigma and discrimination against those with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Natali said the COVID-19 pandemic also led to the exacerbation of stigma and discrimination against those with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

“It's even more difficult to actually just be a part of the community and to do everyday things. So, in some ways, that means that the normal for people with intellectual disabilities hasn't changed but really that isolation has been exacerbated,” he said.

“It's even more difficult to actually just be a part of the community and to do everyday things. So, in some ways, that means that the normal for people with intellectual disabilities hasn't changed but really that isolation has been exacerbated,” he said.

Stigma and discrimination against PWDs are not only felt from health care services and professionals. They also experience this in seeking aid.

Stigma and discrimination against PWDs are not only felt from health care services and professionals. They also experience this in seeking aid.

ADVERTISEMENT

Donaire’s bad experience in getting financial assistance for her son led her to no longer attempt a second try. She said that after spending around P300 on transportation, P400 on document requirements, and P1,200 for the check-up, the P2,000 financial assistance felt like nothing.

Donaire’s bad experience in getting financial assistance for her son led her to no longer attempt a second try. She said that after spending around P300 on transportation, P400 on document requirements, and P1,200 for the check-up, the P2,000 financial assistance felt like nothing.

“Ang tagal kong inantay hindi naman pala binigay. Tapos nung finollow up ko ‘yung financial ko sabi nag-expire na raw ‘yung pera na P2,000. Lagi akong nag-follow up don, sabi lang nila tatawag, tatawag pero hindi naman, kaya hindi na ako nag-ulit,” she shared.

“Ang tagal kong inantay hindi naman pala binigay. Tapos nung finollow up ko ‘yung financial ko sabi nag-expire na raw ‘yung pera na P2,000. Lagi akong nag-follow up don, sabi lang nila tatawag, tatawag pero hindi naman, kaya hindi na ako nag-ulit,” she shared.

(I waited for so long and yet they still didn’t give it to me. I kept following up my financial assistance; they said the P2,000 had already expired. I keep following it up; they always told me they would call but I never received any. That’s why I never did it again.)

(I waited for so long and yet they still didn’t give it to me. I kept following up my financial assistance; they said the P2,000 had already expired. I keep following it up; they always told me they would call but I never received any. That’s why I never did it again.)

It was an experience that also resonated with Lim after being told she was “not a priority” when she tried to seek financial assistance for her son’s costly occupational and physical therapy sessions.

It was an experience that also resonated with Lim after being told she was “not a priority” when she tried to seek financial assistance for her son’s costly occupational and physical therapy sessions.

“Nagpasa ako, sabi sa'kin ‘hindi namin priority ‘yan...’ hindi kami priority na bigyan ng medical assistance,” she shared.

“Nagpasa ako, sabi sa'kin ‘hindi namin priority ‘yan...’ hindi kami priority na bigyan ng medical assistance,” she shared.

ADVERTISEMENT

(I passed the requirements and what they only said was ‘that’s not our priority...’ we weren’t a priority to be given medical assistance.)

(I passed the requirements and what they only said was ‘that’s not our priority...’ we weren’t a priority to be given medical assistance.)

After being rejected to receive the financial assistance she gravely needed for her son’s therapy, she voiced out that being called “not a priority” is heartbreaking for parents who encounter a similar situation.

After being rejected to receive the financial assistance she gravely needed for her son’s therapy, she voiced out that being called “not a priority” is heartbreaking for parents who encounter a similar situation.

“Naiintindihan naman po namin ‘yung may mga operation, ‘yung mga dialysis [patients] pero ‘wag niyo naman sabihin na hindi kami priority,” she added.

“Naiintindihan naman po namin ‘yung may mga operation, ‘yung mga dialysis [patients] pero ‘wag niyo naman sabihin na hindi kami priority,” she added.

(We understand those that need their operation, those who are dialysis [patients] but I just hope they wouldn’t say we are 'not a priority.')

(We understand those that need their operation, those who are dialysis [patients] but I just hope they wouldn’t say we are 'not a priority.')

Facing stigma and discrimination in acquiring the financial assistance she needed for her son’s therapy sessions, Lim said she still hopes that processing these requirements and acquiring aid would no longer be exhausting and expensive in the future.

Facing stigma and discrimination in acquiring the financial assistance she needed for her son’s therapy sessions, Lim said she still hopes that processing these requirements and acquiring aid would no longer be exhausting and expensive in the future.

ADVERTISEMENT

Rojas explained that this situation could be seen as a general experience for families with special needs children but it is “not a general truth” as the conditions highly depend on the local government unit (LGU) in their area.

Rojas explained that this situation could be seen as a general experience for families with special needs children but it is “not a general truth” as the conditions highly depend on the local government unit (LGU) in their area.

He said “welfare is a bottomless pit” and that it’s a constant give and take between the government and its constituents.

He said “welfare is a bottomless pit” and that it’s a constant give and take between the government and its constituents.

“’Yan ang dapat pag-isipan ng gobyerno, ‘yang welfare [on] how to manage it very well... [kasi] kahit bilyon-bilyon pa ‘yan, i-divide mo sa Pilipino, kulang ‘yan. Hindi ganoon kalaki ‘yan. We are not a rich country,” he added

“’Yan ang dapat pag-isipan ng gobyerno, ‘yang welfare [on] how to manage it very well... [kasi] kahit bilyon-bilyon pa ‘yan, i-divide mo sa Pilipino, kulang ‘yan. Hindi ganoon kalaki ‘yan. We are not a rich country,” he added

Members of CP Cares PH said despite the inclusion of children with developmental disabilities in PhilHealth’s Z benefits, they have yet to avail and enjoy this benefit package from the government.

Members of CP Cares PH said despite the inclusion of children with developmental disabilities in PhilHealth’s Z benefits, they have yet to avail and enjoy this benefit package from the government.

In Z benefits, children with developmental disabilities are entitled to assessment and discharge assessment ranging from P3,626 to P5,276 and rehabilitation therapy sessions costing P5,000 per set. For those who are eligible, they can only avail a maximum of nine sets of therapies and each set of therapies has a maximum of 10 sessions.

In Z benefits, children with developmental disabilities are entitled to assessment and discharge assessment ranging from P3,626 to P5,276 and rehabilitation therapy sessions costing P5,000 per set. For those who are eligible, they can only avail a maximum of nine sets of therapies and each set of therapies has a maximum of 10 sessions.

ADVERTISEMENT

“’Yung ospital na tinanungan ko hindi pa daw nila ina-accept 'yung Z benefits na tinatawag na project ng PhilHealth so san lang ba siya pwedeng gamitin? ‘Yun ang tanong. Bakit nila ibabalita na siyempre kami masaya na may ganyang project ang gobyerno pero hindi naman pala accredited sa ibang ospital,” one member said.

“’Yung ospital na tinanungan ko hindi pa daw nila ina-accept 'yung Z benefits na tinatawag na project ng PhilHealth so san lang ba siya pwedeng gamitin? ‘Yun ang tanong. Bakit nila ibabalita na siyempre kami masaya na may ganyang project ang gobyerno pero hindi naman pala accredited sa ibang ospital,” one member said.

She added that only those undergoing chemotherapy were given such benefits in the hospital she inquired at, leaving her and her son with disability to feel discriminated by the system.

She added that only those undergoing chemotherapy were given such benefits in the hospital she inquired at, leaving her and her son with disability to feel discriminated by the system.

Existing benefits remain a scarce commodity for families who want to acquire additional help for their children’s medical needs and with inadequate implementation in the grassroots level, they will have to constantly compete with other PWDs who need it as well.

Existing benefits remain a scarce commodity for families who want to acquire additional help for their children’s medical needs and with inadequate implementation in the grassroots level, they will have to constantly compete with other PWDs who need it as well.

To these mothers, being treated poorly by health care providers, rejected of financial assistances and being called “not a priority” comes off as discriminating.

To these mothers, being treated poorly by health care providers, rejected of financial assistances and being called “not a priority” comes off as discriminating.

The support they need

Families with special needs children bear the weight of medical costs, development regressions and discrimination even more under the COVID-19 pandemic as the health community continues to be overwhelmed in managing the crisis.

Families with special needs children bear the weight of medical costs, development regressions and discrimination even more under the COVID-19 pandemic as the health community continues to be overwhelmed in managing the crisis.

ADVERTISEMENT

But how can this burden be eased for them?

But how can this burden be eased for them?

For Cordova and Lim, more awareness and support for their children’s health and development struggles in the pandemic will greatly ease the daily burdens they carry.

For Cordova and Lim, more awareness and support for their children’s health and development struggles in the pandemic will greatly ease the daily burdens they carry.

“Sana po mabigyang silip, mabigyang tulong, mabigyang pansin din... kahit paano po. Iba ‘yung halos busy sila pero ‘yung hindi pa sila napansin ‘yung mga ganitong autistic po,” Cordova said.

“Sana po mabigyang silip, mabigyang tulong, mabigyang pansin din... kahit paano po. Iba ‘yung halos busy sila pero ‘yung hindi pa sila napansin ‘yung mga ganitong autistic po,” Cordova said.

(I hope they can see us, help us, pay attention to us. They are busy but they tend to overlook us, those that have children with autism.)

(I hope they can see us, help us, pay attention to us. They are busy but they tend to overlook us, those that have children with autism.)

This is a sentiment Natali agrees with: “I believe that it is a wider societal shift, we need to see an attitude. That is what's going to allow people with intellectual disabilities to feel comfortable.”

This is a sentiment Natali agrees with: “I believe that it is a wider societal shift, we need to see an attitude. That is what's going to allow people with intellectual disabilities to feel comfortable.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Donaire on the other hand said cash aid should be given to families with special needs children to alleviate expenses on therapy and medication as the existing financial assistance is not enough to cover the costs.

Donaire on the other hand said cash aid should be given to families with special needs children to alleviate expenses on therapy and medication as the existing financial assistance is not enough to cover the costs.

Echoing improvements on acquiring financial assistance, Santos said institutions should also simplify requirements and qualifications for parents with special needs children, adding to the call for a more inclusive and accessible health care community.

Echoing improvements on acquiring financial assistance, Santos said institutions should also simplify requirements and qualifications for parents with special needs children, adding to the call for a more inclusive and accessible health care community.

“If standardized lahat, may mas madaling access kung paano kami makakapag-apply, makakapag-avail ng mga benefits, makakabawas po ‘yun sa burden. Hindi po namin kailangan pumila, iiwan anak namin dito kasi kailangan namin pumila doon,” she voiced out.

“If standardized lahat, may mas madaling access kung paano kami makakapag-apply, makakapag-avail ng mga benefits, makakabawas po ‘yun sa burden. Hindi po namin kailangan pumila, iiwan anak namin dito kasi kailangan namin pumila doon,” she voiced out.

(If everything is standardized, we will have easier access on how we can apply and avail the benefits which can ease some of the burden. We wouldn’t need to line up, to leave our child behind because we needed to go somewhere else.)

(If everything is standardized, we will have easier access on how we can apply and avail the benefits which can ease some of the burden. We wouldn’t need to line up, to leave our child behind because we needed to go somewhere else.)

For a mother who also went through a lot in the past two years of the pandemic, Santos said that while awareness and increased financial assistance can help alleviate the struggles their family goes through, real change can only come when programs for special needs children are not only enacted under the law but are institutionalized even in far-flung communities outside of Metro Manila.

For a mother who also went through a lot in the past two years of the pandemic, Santos said that while awareness and increased financial assistance can help alleviate the struggles their family goes through, real change can only come when programs for special needs children are not only enacted under the law but are institutionalized even in far-flung communities outside of Metro Manila.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Kapag kasi hindi na-institutionalize ‘yung mga programs and services para sa mga PWD, kahit gaano kaganda ‘yung batas, pero hindi yon nai-institutionalize, hindi mabababa ng maayos 'yan ng grassroots. Hindi namin napapakinabangan, hindi namin nararamdaman,” she added.

“Kapag kasi hindi na-institutionalize ‘yung mga programs and services para sa mga PWD, kahit gaano kaganda ‘yung batas, pero hindi yon nai-institutionalize, hindi mabababa ng maayos 'yan ng grassroots. Hindi namin napapakinabangan, hindi namin nararamdaman,” she added.

(If we don’t institutionalize the programs and services for PWDs, no matter how great the laws are, it wouldn’t be felt in the grassroots level. We wouldn’t benefit from it; we wouldn’t feel it.)

(If we don’t institutionalize the programs and services for PWDs, no matter how great the laws are, it wouldn’t be felt in the grassroots level. We wouldn’t benefit from it; we wouldn’t feel it.)

In response to this call, Rojas said the NCDA would continue to make effort in improving health and welfare support for persons with disabilities in the Philippines.

In response to this call, Rojas said the NCDA would continue to make effort in improving health and welfare support for persons with disabilities in the Philippines.

“Bilang isang maliit na ahensya ng gobyerno hindi po naman natin kaya talaga na maserbisyuhan ang lahat pero sinisikap natin na karamihan mabigay at ma-satisfy kung kinakailangan,” he added.

“Bilang isang maliit na ahensya ng gobyerno hindi po naman natin kaya talaga na maserbisyuhan ang lahat pero sinisikap natin na karamihan mabigay at ma-satisfy kung kinakailangan,” he added.

As the COVID-19 pandemic still lingers, families with special needs children continue to call for heightened awareness, inclusive and sufficient health care and eradication of stigma and discrimination in their community in the Philippines.

As the COVID-19 pandemic still lingers, families with special needs children continue to call for heightened awareness, inclusive and sufficient health care and eradication of stigma and discrimination in their community in the Philippines.

December 3 is the International Day for Persons with Disabilities, with the theme “Leadership and participation of persons with disabilities toward an inclusive, accessible and sustainable post-COVID-19 world.”

Read More:

COVID-19

pandemic

PWDs

special needs

children

disabilities

PWD aid COVID-19

struggles COVID special needs

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT