The art find of the century or its greatest hoax | ABS-CBN

ADVERTISEMENT

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

The art find of the century or its greatest hoax

The art find of the century or its greatest hoax

Mookie Katigbak-Lacuesta,

ANCX

Published Aug 29, 2018 10:22 PM PHT

|

Updated Sep 22, 2018 09:54 AM PHT

There is no national art treasure more important than the Spoliarium. Every nation has its equivalent masterpiece— Spain has the Guernica, France has Liberty Leading the People, the Netherlands has the Night Watch, and we have Luna’s iconic gladiator.

There is no national art treasure more important than the Spoliarium. Every nation has its equivalent masterpiece— Spain has the Guernica, France has Liberty Leading the People, the Netherlands has the Night Watch, and we have Luna’s iconic gladiator.

It’s the first artwork we’re shown in our childhood field trips to the National Museum, and it’s commonly held as our national story. Which history teacher hasn’t told us that the gladiator is the only staying symbol of our nation in distress, dragged as he is through the dark underbelly of the world’s most iconic arena. Weren’t we, Father Cruz would have asked, also hauled through history by the hands of our longest colonial master?

It’s the first artwork we’re shown in our childhood field trips to the National Museum, and it’s commonly held as our national story. Which history teacher hasn’t told us that the gladiator is the only staying symbol of our nation in distress, dragged as he is through the dark underbelly of the world’s most iconic arena. Weren’t we, Father Cruz would have asked, also hauled through history by the hands of our longest colonial master?

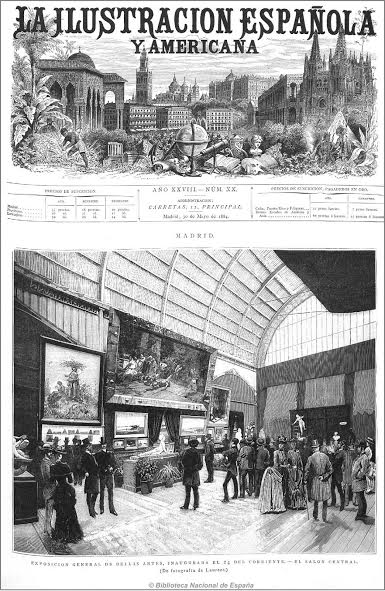

Ironically, it was this very painting that won Juan Luna, a mere colonial subject, a First Class Medal in the Madrid Exposition of 1884. Through his work, he showed the primacy of the Filipino in the international art arena, even as he languished in his home country. The Spoliarium was both symbol and masterpiece, and the view has changed very little over the years.

Ironically, it was this very painting that won Juan Luna, a mere colonial subject, a First Class Medal in the Madrid Exposition of 1884. Through his work, he showed the primacy of the Filipino in the international art arena, even as he languished in his home country. The Spoliarium was both symbol and masterpiece, and the view has changed very little over the years.

“Inasmuch as Luna is seen as a saint, the Spoliarium is a holy relic because it represents the birth of a nation,” says Richie Lerma, advisor to the Salcedo Auctions.

“Inasmuch as Luna is seen as a saint, the Spoliarium is a holy relic because it represents the birth of a nation,” says Richie Lerma, advisor to the Salcedo Auctions.

ADVERTISEMENT

Recent years have spawned a new nationalism in the next generation: Rizal has been in cinema for decades, and the Luna brothers have made something of a comeback in the past few years, with the movie "Heneral Luna" capturing the nation’s imagination and heart a scant three years ago. One of the last scenes has the slain general being dragged, gladiator-like, through rubble and mud—we had that Aha moment, and brushed away that stray eyelash, or popcorn salt, whatever you like, from the corners of our eyes. We’re at a point in our history where we crave our heroes, and for the past few years, it’s meant the Luna brothers. "Heneral Luna" came out in 2015, and the Juan Luna paintings displayed in the National Gallery in Singapore in 2016.

Recent years have spawned a new nationalism in the next generation: Rizal has been in cinema for decades, and the Luna brothers have made something of a comeback in the past few years, with the movie "Heneral Luna" capturing the nation’s imagination and heart a scant three years ago. One of the last scenes has the slain general being dragged, gladiator-like, through rubble and mud—we had that Aha moment, and brushed away that stray eyelash, or popcorn salt, whatever you like, from the corners of our eyes. We’re at a point in our history where we crave our heroes, and for the past few years, it’s meant the Luna brothers. "Heneral Luna" came out in 2015, and the Juan Luna paintings displayed in the National Gallery in Singapore in 2016.

What comes next is either the greatest discovery, or the biggest hoax the local art world has seen in decades. A miniature Spoliarium has been found in a private collection. And its authenticity checks out.

What comes next is either the greatest discovery, or the biggest hoax the local art world has seen in decades. A miniature Spoliarium has been found in a private collection. And its authenticity checks out.

The mysterious e-mail

Early this year, Lerma was contacted by a private collector based in Spain—his family has a painting in their possession, he writes in an unexpected e-mail. It was introduced as a boceto of the Spoliairum—for the uninitiated, a boceto is a sketch or a study.

Early this year, Lerma was contacted by a private collector based in Spain—his family has a painting in their possession, he writes in an unexpected e-mail. It was introduced as a boceto of the Spoliairum—for the uninitiated, a boceto is a sketch or a study.

“They had a photo of it, it wasn’t even taken professionally,” Lerma says. Further inspection showed that it was a miniature version of the Spoliarium—less figurative and more impressionistic than the original, but unmistakably a study of the Luna masterpiece.

“They had a photo of it, it wasn’t even taken professionally,” Lerma says. Further inspection showed that it was a miniature version of the Spoliarium—less figurative and more impressionistic than the original, but unmistakably a study of the Luna masterpiece.

“I was intrigued,” Lerma says, “but I always take these things with a grain of salt. I’m always suspicious whenever claims are made. I come from a museum and research background—I always start with questions and I work my way backwards.”

“I was intrigued,” Lerma says, “but I always take these things with a grain of salt. I’m always suspicious whenever claims are made. I come from a museum and research background—I always start with questions and I work my way backwards.”

In this case, there were more questions than answers and Lerma had his doubts. And then he saw the signature inscribed on the lower right hand corner of the painting.

In this case, there were more questions than answers and Lerma had his doubts. And then he saw the signature inscribed on the lower right hand corner of the painting.

It was done in Luna’s distinctive bold letters: spoliarium boceto, with Luna’s name, and the place and year of its creation (Rome, 1883). But what intrigued Lerma was the inscription of a strange glyph beside the artist’s name.

It was done in Luna’s distinctive bold letters: spoliarium boceto, with Luna’s name, and the place and year of its creation (Rome, 1883). But what intrigued Lerma was the inscription of a strange glyph beside the artist’s name.

It was done in baybayin.

It was done in baybayin.

Bulan, it read, Ilokano for moon—the pre-Spanish name of Luna himself. History tells us that Luna was born in Ilocos Norte, and that he was especially proud of our pre-colonial past—some of his historically acknowledged and exhibited paintings have been known to bear the same syllables of the ancient alphabet.

Bulan, it read, Ilokano for moon—the pre-Spanish name of Luna himself. History tells us that Luna was born in Ilocos Norte, and that he was especially proud of our pre-colonial past—some of his historically acknowledged and exhibited paintings have been known to bear the same syllables of the ancient alphabet.

Another telltale detail was the woman looking away from the spectacle. It can’t escape notice that she’s dressed in one of Luna’s signature colors—a muted hue known as Aegean blue.

Another telltale detail was the woman looking away from the spectacle. It can’t escape notice that she’s dressed in one of Luna’s signature colors—a muted hue known as Aegean blue.

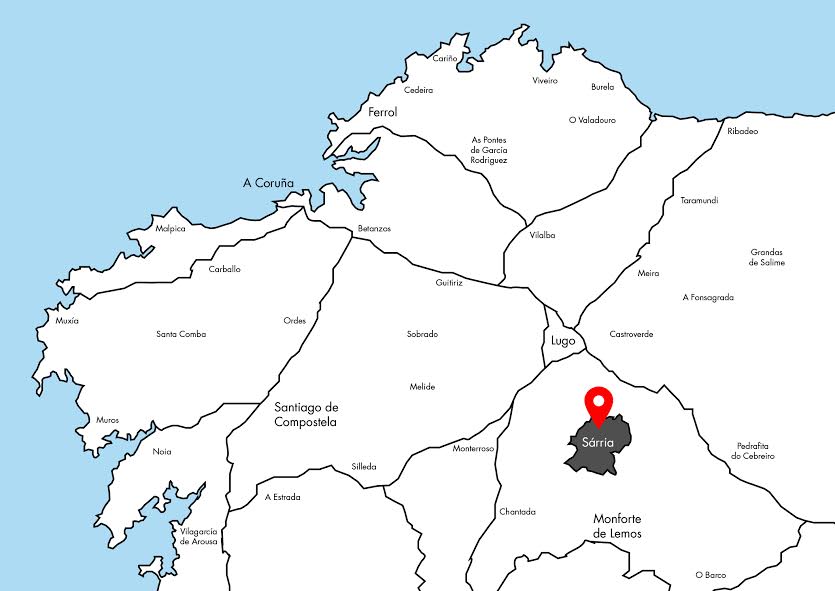

Both were heart-stopping details for Lerma. He packed his bags and headed to Sarria, a small town in Galicia, Spain, where the family hailed—and where the miniature version of our country’s most iconic painting was kept.

Both were heart-stopping details for Lerma. He packed his bags and headed to Sarria, a small town in Galicia, Spain, where the family hailed—and where the miniature version of our country’s most iconic painting was kept.

Journey to Sárria: Meeting the Castiñeira heirs

When he met the family who contacted him, Lerma was told that they had another surprise for him. It was a painting of a female artist done in the style of Felix Resurreción Hidalgo—one of Luna’s rivals and compatriots.

When he met the family who contacted him, Lerma was told that they had another surprise for him. It was a painting of a female artist done in the style of Felix Resurreción Hidalgo—one of Luna’s rivals and compatriots.

Lerma asked himself what connection could possibly exist between the Luna boceto and the Hidalgo—and what historical accident would allow for both paintings to fall into the hands of this one family?

Lerma asked himself what connection could possibly exist between the Luna boceto and the Hidalgo—and what historical accident would allow for both paintings to fall into the hands of this one family?

“So that alone piqued my interest even more,” he says. “I wouldn’t say that I’m an expert at Hidalgo, but I’ve seen enough Hidalgos to know his brushstroke, his palette, and his subject matter, to know that it was authentic.”

“So that alone piqued my interest even more,” he says. “I wouldn’t say that I’m an expert at Hidalgo, but I’ve seen enough Hidalgos to know his brushstroke, his palette, and his subject matter, to know that it was authentic.”

At this point, nothing more can be revealed about the family apart from the fact that they’re the living heirs of one Doña Maria Nuñez Rodriguez, daughter-in-law of Don Xosé Vázquez Castiñeira. It happens that Castiñeira was sometime mayor of Sárria. He was an acquaintance at least, and a friend at best, of another of Sárria’s proudest accomplishments—a businessman by the name of Don Matías Lopez. Lopez owned one of the biggest confectionary empires in the kingdom. At some point, his company was known to have supplied four-fifths of all the chocolates consumed throughout Spain.

At this point, nothing more can be revealed about the family apart from the fact that they’re the living heirs of one Doña Maria Nuñez Rodriguez, daughter-in-law of Don Xosé Vázquez Castiñeira. It happens that Castiñeira was sometime mayor of Sárria. He was an acquaintance at least, and a friend at best, of another of Sárria’s proudest accomplishments—a businessman by the name of Don Matías Lopez. Lopez owned one of the biggest confectionary empires in the kingdom. At some point, his company was known to have supplied four-fifths of all the chocolates consumed throughout Spain.

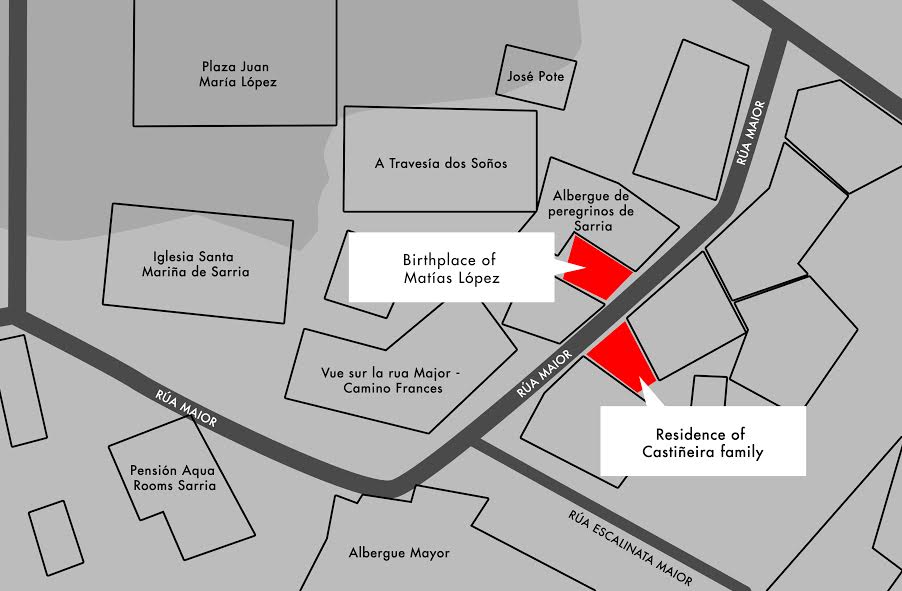

There is documentary evidence that both Castiñeira and Lopez were together at different events—not such a strange turn of events given their social positions as mayor and tycoon of the same small town. It is alleged that the paintings passed from Lopez’s hands to Castiñeira’s. Adding credence to this theory was Lerma’s discovery that Lopez’s birthplace faced the Castiñeira home on the same street.

There is documentary evidence that both Castiñeira and Lopez were together at different events—not such a strange turn of events given their social positions as mayor and tycoon of the same small town. It is alleged that the paintings passed from Lopez’s hands to Castiñeira’s. Adding credence to this theory was Lerma’s discovery that Lopez’s birthplace faced the Castiñeira home on the same street.

The Lopez connection

In 1889, the biggest universal exposition revealed the Eiffel Tower to the world. It was called the Exposition Universelle, and its main attraction was Gustave Eiffel’s iconic wrought-iron tower. Among the exposition’s highlights was a Spanish pavilion built on the River Seine.

In 1889, the biggest universal exposition revealed the Eiffel Tower to the world. It was called the Exposition Universelle, and its main attraction was Gustave Eiffel’s iconic wrought-iron tower. Among the exposition’s highlights was a Spanish pavilion built on the River Seine.

“Inside that pavilion—besides the industries, the arts, the produce, the crafts of Spain, there were paintings of eight artists,” Lerma says. “Two of whom were Luna and Hidalgo.” Documents show that Matías Lopez was the commissioner of the pavilion. “Basically the organizer and patron of the Spanish Pavilion,” Lerma says.

“Inside that pavilion—besides the industries, the arts, the produce, the crafts of Spain, there were paintings of eight artists,” Lerma says. “Two of whom were Luna and Hidalgo.” Documents show that Matías Lopez was the commissioner of the pavilion. “Basically the organizer and patron of the Spanish Pavilion,” Lerma says.

As commissioner, Lopez met Luna and Hidalgo. Lopez would also have instantly recognized the boceto, given that the Spoliarium was such a massive hit in the 1884 Madrid Exposition. “It would stand to reason that Matias Lopez would have been familiar with the painting, not just for its renown in 1884, but its continuing renown as well,” Lerma says.

As commissioner, Lopez met Luna and Hidalgo. Lopez would also have instantly recognized the boceto, given that the Spoliarium was such a massive hit in the 1884 Madrid Exposition. “It would stand to reason that Matias Lopez would have been familiar with the painting, not just for its renown in 1884, but its continuing renown as well,” Lerma says.

In 1889, Luna and Hidalgo both had studios in Paris. As commissioner of the Spanish Pavilion, Lopez wouldn’t have just met the artists, he would have visited them in their studios, Lerma says. Because Luna brought his winning masterpiece to Paris with him, it stands to reason that he would have brought the boceto to Paris as well. “Either Lopez bought the boceto from him, or he gave it to Lopez as a gift,” Lerma says.

In 1889, Luna and Hidalgo both had studios in Paris. As commissioner of the Spanish Pavilion, Lopez wouldn’t have just met the artists, he would have visited them in their studios, Lerma says. Because Luna brought his winning masterpiece to Paris with him, it stands to reason that he would have brought the boceto to Paris as well. “Either Lopez bought the boceto from him, or he gave it to Lopez as a gift,” Lerma says.

The Hidalgo, done in the same wispy, dream-like style of his Paris period, would also have been acquired by Lopez at this time. Staggeringly, it is the same painting Lerma saw in the Sarria home of the Castiñiera heirs. A photograph reveals that this painting is called “La Pintura,” and that it was exhibited earlier by Luna in an exhibition he curated in Madrid in 1883, along with his boceto.

The Hidalgo, done in the same wispy, dream-like style of his Paris period, would also have been acquired by Lopez at this time. Staggeringly, it is the same painting Lerma saw in the Sarria home of the Castiñiera heirs. A photograph reveals that this painting is called “La Pintura,” and that it was exhibited earlier by Luna in an exhibition he curated in Madrid in 1883, along with his boceto.

At the time of his death, Lopez would have passed on the two artworks to Castiñiera. In time, Castiñiera would have passed them on to his daughter-in-law, and she to her heirs—descendants of whom are the same family who contacted Lerma in early 2018.

At the time of his death, Lopez would have passed on the two artworks to Castiñiera. In time, Castiñiera would have passed them on to his daughter-in-law, and she to her heirs—descendants of whom are the same family who contacted Lerma in early 2018.

Found masterpiece or top detective fiction?

At the time of Lerma’s expedition to Sarria, parallel investigations were also being conducted by his researchers on the life and travels of Luna. Between the 1884 Madrid Exposition, and his Paris years leading up to the 1889 Exposition Universelle, the timeline checks out.

At the time of Lerma’s expedition to Sarria, parallel investigations were also being conducted by his researchers on the life and travels of Luna. Between the 1884 Madrid Exposition, and his Paris years leading up to the 1889 Exposition Universelle, the timeline checks out.

Lending credence to his story is the discovery of the Luna glyph—a detail renowned historian and Rizal enthusiast, Ambeth Ocampo, references in an article pointing to two other Luna paintings bearing the same baybayin syllables. Lerma’s catalogue reveals that examination under UV light shows that the varnish and patina layers of the boceto “fluoresce to a greenish glow,” which means that the artwork was created from over a century ago. In the catalogue notes, it is indicated that the Luna signature disappears under UV light, which means that it was signed upon the completion of the painting by the “original hand that created the artwork.” Anything postdating the work would turn up on the surface. The use of Luna’s signature blue, as seen on the woman turning away from the spectacle, also lends truth to the authenticity of the piece.

Lending credence to his story is the discovery of the Luna glyph—a detail renowned historian and Rizal enthusiast, Ambeth Ocampo, references in an article pointing to two other Luna paintings bearing the same baybayin syllables. Lerma’s catalogue reveals that examination under UV light shows that the varnish and patina layers of the boceto “fluoresce to a greenish glow,” which means that the artwork was created from over a century ago. In the catalogue notes, it is indicated that the Luna signature disappears under UV light, which means that it was signed upon the completion of the painting by the “original hand that created the artwork.” Anything postdating the work would turn up on the surface. The use of Luna’s signature blue, as seen on the woman turning away from the spectacle, also lends truth to the authenticity of the piece.

Lerma’s sleuthing itself has turned up a story that’s stranger than fiction—it would take Le Carre’s or Byatt’s imagination to come up with such a plot; that the mind behind one of our leading auction houses could turn detective fictionist on us, and fabulate such a story, would challenge its reputation and name. The stakes are too high for the auction house, should the story be revealed as a scintillating lie.

Lerma’s sleuthing itself has turned up a story that’s stranger than fiction—it would take Le Carre’s or Byatt’s imagination to come up with such a plot; that the mind behind one of our leading auction houses could turn detective fictionist on us, and fabulate such a story, would challenge its reputation and name. The stakes are too high for the auction house, should the story be revealed as a scintillating lie.

The boceto itself will be up for preview for the Well-Appointed Life auction from September 13-21, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., at the Gallery Level 3, at the Peninsula Manila. It will be up for auction on September 22, at the Rigodon Ballroom, also at the Peninsula.

The boceto itself will be up for preview for the Well-Appointed Life auction from September 13-21, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., at the Gallery Level 3, at the Peninsula Manila. It will be up for auction on September 22, at the Rigodon Ballroom, also at the Peninsula.

If it’s the true boceto of our national masterpiece, it could well be the stuff of history, lending our hearts a staggering new beat, and our cultural heritage a staggering new addition.

If it’s the true boceto of our national masterpiece, it could well be the stuff of history, lending our hearts a staggering new beat, and our cultural heritage a staggering new addition.

For now, it’s still all up in the air, as scintillating a story as it gets, as yet neither truth nor fiction.

For now, it’s still all up in the air, as scintillating a story as it gets, as yet neither truth nor fiction.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT