OPINION: Duterte government slashed disaster fund without explanation | ABS-CBN

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

OPINION: Duterte government slashed disaster fund without explanation

OPINION: Duterte government slashed disaster fund without explanation

Raissa Robles

Published Aug 13, 2018 01:19 AM PHT

And why did his hand-picked disaster operations chief go on vacay amid flood warnings?

Disaster is part of life in the Philippines.

Disaster is part of life in the Philippines.

By the time many Filipinos turn 21, they would have experienced a volcanic eruption, several strong earthquakes and over 400 storms – dozens of them worsened by deep floods, violent winds and landslides.

By the time many Filipinos turn 21, they would have experienced a volcanic eruption, several strong earthquakes and over 400 storms – dozens of them worsened by deep floods, violent winds and landslides.

So it is rather hard to understand why President Rodrigo Duterte has kept slashing the disaster fund. Because of this, only P7.6 billion (roughly US$150 million) is left for natural disasters this year.

So it is rather hard to understand why President Rodrigo Duterte has kept slashing the disaster fund. Because of this, only P7.6 billion (roughly US$150 million) is left for natural disasters this year.

I hope the ongoing floods in and around do not totally wipe out this sum.

I hope the ongoing floods in and around do not totally wipe out this sum.

ADVERTISEMENT

And we still have to go through the “ber” months when deadlier typhoons usually come.

And we still have to go through the “ber” months when deadlier typhoons usually come.

*****

*****

Duterte also appointed former Navy Captain Nicanor Faeldon as the deputy administrator for operations of the Office of Civil Defense (OCD). After removing him as Customs Commissioner.

Duterte also appointed former Navy Captain Nicanor Faeldon as the deputy administrator for operations of the Office of Civil Defense (OCD). After removing him as Customs Commissioner.

The OCD is the operational arm of the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC). NDRRMC, created in the tragic aftermath of Typhoon Ondoy (international code name – Ketsana), is the agency that calls the shots during ongoing disasters, like this one.

The OCD is the operational arm of the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC). NDRRMC, created in the tragic aftermath of Typhoon Ondoy (international code name – Ketsana), is the agency that calls the shots during ongoing disasters, like this one.

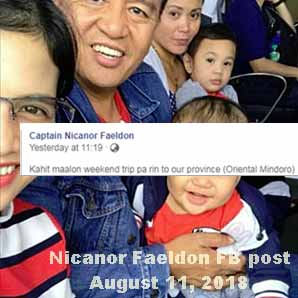

So why did Faeldon post this photo on his Facebook page yesterday—amid heavy flood warnings—that he was on his way to Oriental Mindoro with his new-born kid and his partner?

So why did Faeldon post this photo on his Facebook page yesterday—amid heavy flood warnings—that he was on his way to Oriental Mindoro with his new-born kid and his partner?

He posted this photo and said, “Kahit maalon weekend trip pa rin to our province (Oriental Mindoro).” [Translation, even if the sea is rough, our weekend trip to our province is on.]

He posted this photo and said, “Kahit maalon weekend trip pa rin to our province (Oriental Mindoro).” [Translation, even if the sea is rough, our weekend trip to our province is on.]

Sure, the NDRRMC has been issuing flood warnings throughout social media and mobile text messages this weekend.

Sure, the NDRRMC has been issuing flood warnings throughout social media and mobile text messages this weekend.

Still, there is nothing like the operations chief manning the battle station at a time like this.

Still, there is nothing like the operations chief manning the battle station at a time like this.

Disaster relief officials are like journalists. They have no day off before, during and after disasters.

Disaster relief officials are like journalists. They have no day off before, during and after disasters.

I’m glad to note, though, that there are local government executives doing their job on disaster relief preparation and operations.

I’m glad to note, though, that there are local government executives doing their job on disaster relief preparation and operations.

Particularly the local executives of Marikina City.

Particularly the local executives of Marikina City.

*****

*****

What I find very interesting is that we have not also heard any presidential palace official nor cabinet official speak out about the ongoing disaster.

What I find very interesting is that we have not also heard any presidential palace official nor cabinet official speak out about the ongoing disaster.

*****

*****

I saw a post by actress Solenn Heussaff on the “sea of garbage” littering Roxas Boulevard in Manila. She urged the government to put more garbage bins in the streets.

I saw a post by actress Solenn Heussaff on the “sea of garbage” littering Roxas Boulevard in Manila. She urged the government to put more garbage bins in the streets.

Perhaps, she does not know, that the usual metal bins found so abundantly in other countries do not work in Metro Manila.

Perhaps, she does not know, that the usual metal bins found so abundantly in other countries do not work in Metro Manila.

They will simply disappear overnight and brought to junk shops for resale.

They will simply disappear overnight and brought to junk shops for resale.

This is also why Manila’s manholes are missing their steel covers. These have also been pried off and sold.

This is also why Manila’s manholes are missing their steel covers. These have also been pried off and sold.

*****

*****

I’ve been covering disasters since the 1990s. But it’s only in recent years that I observed a sea change in the government’s attitude toward disasters.

I’ve been covering disasters since the 1990s. But it’s only in recent years that I observed a sea change in the government’s attitude toward disasters.

I wrote about this sea change in this piece recently published in D+ C (Development and Cooperation), a magazine funded by Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development and published on behalf of ENGAGEMENT GLOBAL.

I wrote about this sea change in this piece recently published in D+ C (Development and Cooperation), a magazine funded by Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development and published on behalf of ENGAGEMENT GLOBAL.

With the permission of D+ C, I am printing part of my article below, with a link to the entire piece on the D+C website.

With the permission of D+ C, I am printing part of my article below, with a link to the entire piece on the D+C website.

DISASTER RISKS: Changing attitude

19/06/2018 – by Raissa Robles

19/06/2018 – by Raissa Robles

Innovative legislation compels authorities in the Philippines to manage and reduce disaster risks systematically. This is a new paradigm. Even though they hit the archipelago regularly, natural calamities were previously seen as one-off events.

Innovative legislation compels authorities in the Philippines to manage and reduce disaster risks systematically. This is a new paradigm. Even though they hit the archipelago regularly, natural calamities were previously seen as one-off events.

Natural disasters are part of life in the Philippines’ over 7,000 islands. By the time many Filipinos turn 21, they are likely to have experienced more than 200 tropical cyclones with top wind speeds of at least 118 km/h. Storms often cause severe flooding and landslides.

Natural disasters are part of life in the Philippines’ over 7,000 islands. By the time many Filipinos turn 21, they are likely to have experienced more than 200 tropical cyclones with top wind speeds of at least 118 km/h. Storms often cause severe flooding and landslides.

Earthquakes and volcano eruptions are common too.

Earthquakes and volcano eruptions are common too.

In 2017, the Philippines with 100 million people ranked third behind the Vanuatu and Tonga, two small Pacific island nations, according to the World Risk Index. The index is compiled by an alliance of German non-governmental organisations (“Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft”) and assesses 173 countries’ exposure to natural disaster risks as well as their ability to cope.

In 2017, the Philippines with 100 million people ranked third behind the Vanuatu and Tonga, two small Pacific island nations, according to the World Risk Index. The index is compiled by an alliance of German non-governmental organisations (“Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft”) and assesses 173 countries’ exposure to natural disaster risks as well as their ability to cope.

“Whether natural hazards turn into disasters depends not only on the intensity of an event but is also crucially determined by a society’s level of development,” says Isagani Serrano, the president of the non-governmental Rural Reconstruction Movement and a co-convenor of Social Watch Philippines.

“Whether natural hazards turn into disasters depends not only on the intensity of an event but is also crucially determined by a society’s level of development,” says Isagani Serrano, the president of the non-governmental Rural Reconstruction Movement and a co-convenor of Social Watch Philippines.

Pedro Walpole of Ateneo de Manila, a highly respected Catholic university, agrees. In his view, natural events like typhoons only become disasters when humans die. His grim forecast is this will continue to happen because “in the Philippines, we have an awful lot of very poor, marginalised people who have no place to go.”

Pedro Walpole of Ateneo de Manila, a highly respected Catholic university, agrees. In his view, natural events like typhoons only become disasters when humans die. His grim forecast is this will continue to happen because “in the Philippines, we have an awful lot of very poor, marginalised people who have no place to go.”

This view is reinforced by Social Watch data:

This view is reinforced by Social Watch data:

* Over half the nation’s people live along coastlines, exposing them to typhoons and storm surges.

* Slightly more than a quarter are so poor that they cannot recover material losses or repair damages.

* One fifth are undernourished, so they are vulnerable to the health challenges of a storm’s aftermath.

* Over half the nation’s people live along coastlines, exposing them to typhoons and storm surges.

* Slightly more than a quarter are so poor that they cannot recover material losses or repair damages.

* One fifth are undernourished, so they are vulnerable to the health challenges of a storm’s aftermath.

Filipino’s traditional attitude to calamities is best expressed by the aphorism “bahala na”,, which means “let’s leave it up to God.” Foreigners often consider it fatalistic. Filipinos seem to be resigned to accept nature’s wrath. The prominent scholar Alfredo Lagmay, who passed away in 2005, proposed a rather different interpretation of “bahala na” however. He argued it invited risk-taking while faced with possible failure. “It gives a person courage to see himself through hard times,” he said. It is “like dancing with the cosmos.”

Filipino’s traditional attitude to calamities is best expressed by the aphorism “bahala na”,, which means “let’s leave it up to God.” Foreigners often consider it fatalistic. Filipinos seem to be resigned to accept nature’s wrath. The prominent scholar Alfredo Lagmay, who passed away in 2005, proposed a rather different interpretation of “bahala na” however. He argued it invited risk-taking while faced with possible failure. “It gives a person courage to see himself through hard times,” he said. It is “like dancing with the cosmos.”

For decades after independence in 1946, government responses to disasters were largely fatalistic and opportunistic. All administrations basically followed the same morning-after-the-storm ritual. The idea was that little could be done to prevent disasters, so policymakers’ job was to deliver relief fast after a disaster struck.

For decades after independence in 1946, government responses to disasters were largely fatalistic and opportunistic. All administrations basically followed the same morning-after-the-storm ritual. The idea was that little could be done to prevent disasters, so policymakers’ job was to deliver relief fast after a disaster struck.

Affected families were crammed in school rooms until floods subsided. Typically, bags of rice and food cans were marked with the name of the politician who doled them out. Relief efforts were thus really re-election efforts. This practice has fallen into disrepute.

Affected families were crammed in school rooms until floods subsided. Typically, bags of rice and food cans were marked with the name of the politician who doled them out. Relief efforts were thus really re-election efforts. This practice has fallen into disrepute.

Apart from handing out supplies, there was no job for local governments. It was the army’s task to conduct search and rescue missions. It also cleared and repaired roads.

Apart from handing out supplies, there was no job for local governments. It was the army’s task to conduct search and rescue missions. It also cleared and repaired roads.

Failure to handle a catastrophe competently could end political careers. Typhoon Ketsana flooded Metro Manila in September 2009. Then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo had groomed her Defense Secretary Gilbert Teodoro to run for president in 2010. He failed miserably to send rubber boats to rescue trapped homeowners from the flood waters – and that contributed to sinking his presidential campaign. Under the impression of the typhoon, however, the government changed its stance.

Failure to handle a catastrophe competently could end political careers. Typhoon Ketsana flooded Metro Manila in September 2009. Then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo had groomed her Defense Secretary Gilbert Teodoro to run for president in 2010. He failed miserably to send rubber boats to rescue trapped homeowners from the flood waters – and that contributed to sinking his presidential campaign. Under the impression of the typhoon, however, the government changed its stance.

Innovative approach

In 2010, the Arroyo-dominated Congress approved landmark legislation. It created the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC). Both disaster risk management (DRM) and disaster risk reduction (DRR) were innovative concepts. The new law fulfilled the Philippines’ commitment to implement the Hyogo Framework for Action, which had been the result of a UN conference on resilience building in Japan in 2005.

In 2010, the Arroyo-dominated Congress approved landmark legislation. It created the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC). Both disaster risk management (DRM) and disaster risk reduction (DRR) were innovative concepts. The new law fulfilled the Philippines’ commitment to implement the Hyogo Framework for Action, which had been the result of a UN conference on resilience building in Japan in 2005.

The new law marked a paradigm shift, according to Carmelita Laverinto of the Office of Civil Defence. She says that governments and relief agencies earlier viewed disasters as “one-off events” and responded accordingly. In her view, neither the social and economic implications of disasters nor their causes were appropriately taken into account.

The new law marked a paradigm shift, according to Carmelita Laverinto of the Office of Civil Defence. She says that governments and relief agencies earlier viewed disasters as “one-off events” and responded accordingly. In her view, neither the social and economic implications of disasters nor their causes were appropriately taken into account.

To read the rest of the English version, please click on this link.

To read the rest of the English version, please click on this link.

*****

*****

A sidebar piece deals with a very frank critique of foreign aid agencies.

A sidebar piece deals with a very frank critique of foreign aid agencies.

HUMANITARIAN AGENCIES

Unspoken competition

Unspoken competition

20/06/2018 – by Raissa Robles

20/06/2018 – by Raissa Robles

Typhoon Haiyan – which was also called Typhoon Yolanda in the Philippines, triggered an enormous and generous outpouring of foreign aid from non-governmental organisations, faith-based charities and UN agencies. One veteran of international disaster relief, however, became keenly aware of the efforts’ downsides.

Typhoon Haiyan – which was also called Typhoon Yolanda in the Philippines, triggered an enormous and generous outpouring of foreign aid from non-governmental organisations, faith-based charities and UN agencies. One veteran of international disaster relief, however, became keenly aware of the efforts’ downsides.

In the devastated city of Tacloban, Karl Gaspar, a Catholic monk, saw NGO workers staying in the most expensive hotels, eating in the best restaurants and cruising in brand new SUVs through streets “where dead bodies wait to be identified and buried in mass graves”. Moreover, he noted that many pledges never materialised. In his book (Gaspar 2014) on the experience, he wrote: “As of 8 September 2014, the country has received P 71 billion ($ 1.626 billion) worth of foreign aid pledges in cash and in kind, but only P 15 billion ($ 349.404 million) has been received so far.”

In the devastated city of Tacloban, Karl Gaspar, a Catholic monk, saw NGO workers staying in the most expensive hotels, eating in the best restaurants and cruising in brand new SUVs through streets “where dead bodies wait to be identified and buried in mass graves”. Moreover, he noted that many pledges never materialised. In his book (Gaspar 2014) on the experience, he wrote: “As of 8 September 2014, the country has received P 71 billion ($ 1.626 billion) worth of foreign aid pledges in cash and in kind, but only P 15 billion ($ 349.404 million) has been received so far.”

To read the rest, please click on this link.

To read the rest, please click on this link.

Read More:

featured blog

blog roll

raissa robles

disaster

Nicanor Faeldon

Office of Civil Defense

habagat

weather

budget

NDRRMC

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT