Opinion: Shrinkflation | ABS-CBN

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

Opinion: Shrinkflation

Opinion: Shrinkflation

Ronald Mendoza and Ayn Torres

Published Jul 02, 2018 09:18 AM PHT

WHAT IS SHRINKFLATION?

At the height of increased world prices of flour in 2008, the price of the Pinoy pan de sal increased by 10 percent to P2.50 per piece. Not all panaderias, however, decided to join the bandwagon.

At the height of increased world prices of flour in 2008, the price of the Pinoy pan de sal increased by 10 percent to P2.50 per piece. Not all panaderias, however, decided to join the bandwagon.

After all, losing a whole neighborhood of loyal customers may be more costly. Some bakers opted to stick to old prices -- but at the expense of Juan eating a smaller piece of his breakfast bread.

After all, losing a whole neighborhood of loyal customers may be more costly. Some bakers opted to stick to old prices -- but at the expense of Juan eating a smaller piece of his breakfast bread.

With his P10 he was still able to buy 6 pieces; but in reality this was only equivalent in nutritional amount to 4 pieces of the previously slightly larger pan de sal.

With his P10 he was still able to buy 6 pieces; but in reality this was only equivalent in nutritional amount to 4 pieces of the previously slightly larger pan de sal.

Price is one of the top considerations when buying food, and consumers will always look for bargains. As most of what we purchase are already staples, who’s to notice on the onset when the goods we constantly put in our baskets appear to be smaller than usual, especially when the price didn’t change at all?

Price is one of the top considerations when buying food, and consumers will always look for bargains. As most of what we purchase are already staples, who’s to notice on the onset when the goods we constantly put in our baskets appear to be smaller than usual, especially when the price didn’t change at all?

ADVERTISEMENT

The impact of inflation pressure is not always in the form of increased prices. As the cost of production becomes more expensive from increased prices of utilities and cost of ingredients, and in the face of very price-sensitive consumers, companies oftentimes protect their market base by making adjustments other than price increases, i.e. by reducing ingredients, altering the packaging, or most commonly, downsizing the product itself.

The impact of inflation pressure is not always in the form of increased prices. As the cost of production becomes more expensive from increased prices of utilities and cost of ingredients, and in the face of very price-sensitive consumers, companies oftentimes protect their market base by making adjustments other than price increases, i.e. by reducing ingredients, altering the packaging, or most commonly, downsizing the product itself.

Although the term has only been coined in recent years, shrinkflation is a strategy that has been known for decades, with the first instance recorded at least as early as 1916 when bakers in the US were found to be producing smaller bread products sold at same prices. Sounds familiar? Needless to say, Filipinos are not immune to this phenomenon.

Although the term has only been coined in recent years, shrinkflation is a strategy that has been known for decades, with the first instance recorded at least as early as 1916 when bakers in the US were found to be producing smaller bread products sold at same prices. Sounds familiar? Needless to say, Filipinos are not immune to this phenomenon.

While the practice has been a lot more common over the past 5 years among producers globally with food and packaging shrinking for over 2,500 products in the shelves from chocolate bars to toilet papers as found by a study in the UK, it is important to look at these occurrences as it happens right in front of our doorstep.

While the practice has been a lot more common over the past 5 years among producers globally with food and packaging shrinking for over 2,500 products in the shelves from chocolate bars to toilet papers as found by a study in the UK, it is important to look at these occurrences as it happens right in front of our doorstep.

In the Philippines, the problem of shrinkflation should not be talked about in the context of a smaller Toblerone chocolate bar, but of our most basic needs.

In the Philippines, the problem of shrinkflation should not be talked about in the context of a smaller Toblerone chocolate bar, but of our most basic needs.

Instant noodles, canned goods, and soap bars, products consumed mostly by the poor, suddenly seem to have loose packaging, or the usually comfortable packaging becomes very tight.

Instant noodles, canned goods, and soap bars, products consumed mostly by the poor, suddenly seem to have loose packaging, or the usually comfortable packaging becomes very tight.

Even rental prices remain at P15,000 a month for a one-bedroom apartment, but property offers have been downsized to now only 45 square meters in floor area. Indeed, the average Juan has been short-changed in more ways than perceived.

Even rental prices remain at P15,000 a month for a one-bedroom apartment, but property offers have been downsized to now only 45 square meters in floor area. Indeed, the average Juan has been short-changed in more ways than perceived.

In the advent of continuously increasing food prices that coincided with the implementation of tax reform schemes in 2018, one may ask how much impact has this really brought to Filipinos. It can be measured in several ways, but the simplest way is to ask: Are NCR minimum wages still enough for Filipino families to afford the daily meal plan prescribed by the government’s “Pinggang Pinoy” program?

In the advent of continuously increasing food prices that coincided with the implementation of tax reform schemes in 2018, one may ask how much impact has this really brought to Filipinos. It can be measured in several ways, but the simplest way is to ask: Are NCR minimum wages still enough for Filipino families to afford the daily meal plan prescribed by the government’s “Pinggang Pinoy” program?

SHRINKING PLATES

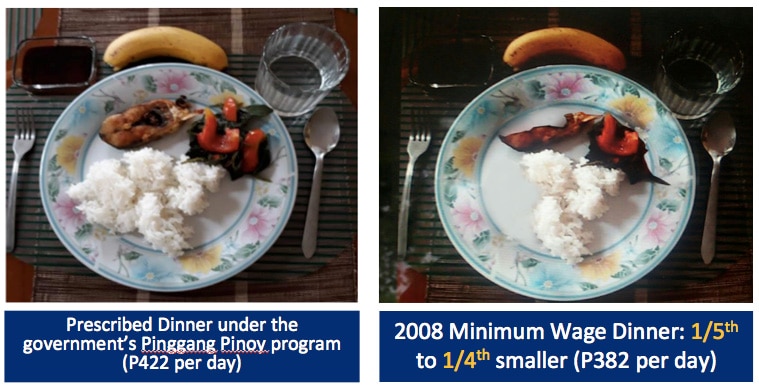

As an illustration of shrinkflation, we turn to the government’s Pinggang Pinoy program, which identifies the prescribed nutritional and food content for three meals for a family of four individuals for a typical day, complete with the government recommended amount of carbohydrates, protein, fish, vegetables and fruits, and a simple snack.

As an illustration of shrinkflation, we turn to the government’s Pinggang Pinoy program, which identifies the prescribed nutritional and food content for three meals for a family of four individuals for a typical day, complete with the government recommended amount of carbohydrates, protein, fish, vegetables and fruits, and a simple snack.

Using the food prices in 2008, during the infamous global food price crisis back then, the Ateneo Policy Center calculated the total cost of food for a family of four under Pinggang Pinoy—roughly around P422 per day.

Using the food prices in 2008, during the infamous global food price crisis back then, the Ateneo Policy Center calculated the total cost of food for a family of four under Pinggang Pinoy—roughly around P422 per day.

We then compare this to the minimum wage ranging from P345 to P382 in NCR back then. Clearly, the minimum wage comes short by around 10 percent to 22 percent.

We then compare this to the minimum wage ranging from P345 to P382 in NCR back then. Clearly, the minimum wage comes short by around 10 percent to 22 percent.

Fast forward 10 years later to the present -- the minimum wage of workers in NCR as of June 2018 is between P475 to P512, which ideally should be able to feed a family of four individuals in a day according to Pinggang Pinoy.

Fast forward 10 years later to the present -- the minimum wage of workers in NCR as of June 2018 is between P475 to P512, which ideally should be able to feed a family of four individuals in a day according to Pinggang Pinoy.

However, the total cost of 3 meals for 4 individuals for a typical day in today’s prices—amounts to P643 per day in 2018 prices. Put simply, the recommended minimum meal by our own government, when calculated using the price data that they also publish, requires an increase of around 26 percent to 35 percent in the NCR minimum wage levels in order for the ordinary worker to be able to afford this.

However, the total cost of 3 meals for 4 individuals for a typical day in today’s prices—amounts to P643 per day in 2018 prices. Put simply, the recommended minimum meal by our own government, when calculated using the price data that they also publish, requires an increase of around 26 percent to 35 percent in the NCR minimum wage levels in order for the ordinary worker to be able to afford this.

CASH TRANSFERS TO THE POOR ARE SHRINKFLATING, TOO

Unsurprisingly, a brief review of the evidence here suggests the poorest of the poor are even less capable of dodging the impact. Like the minimum wage that lost real value over time due to inflation, the conditional cash transfers provided by the DSWD to more than 4 million beneficiary households through the 4Ps program has eroded in real value as well.

Unsurprisingly, a brief review of the evidence here suggests the poorest of the poor are even less capable of dodging the impact. Like the minimum wage that lost real value over time due to inflation, the conditional cash transfers provided by the DSWD to more than 4 million beneficiary households through the 4Ps program has eroded in real value as well.

The estimated erosion has been calculated by the Ateneo Policy Center at around 28 percent in 2013, 5 years after implementation. Furthermore, with the first quarter inflation rate in 2018, real cash transfers would have further eroded by around 39 percent compared to PNoy-era cash grants, but the erosion has been slightly mitigated to around 21 percent thanks in part to an additional P600 rice subsidy in 2017 introduced by the Duterte administration. This assumes, of course, that the rice subsidy is flawlessly delivered.

The estimated erosion has been calculated by the Ateneo Policy Center at around 28 percent in 2013, 5 years after implementation. Furthermore, with the first quarter inflation rate in 2018, real cash transfers would have further eroded by around 39 percent compared to PNoy-era cash grants, but the erosion has been slightly mitigated to around 21 percent thanks in part to an additional P600 rice subsidy in 2017 introduced by the Duterte administration. This assumes, of course, that the rice subsidy is flawlessly delivered.

STOPPING SHRINKFLATION

The looming impacts of food price increases to the average Filipino’s purchasing power call for a second and harder look at policy priorities in the country.

The looming impacts of food price increases to the average Filipino’s purchasing power call for a second and harder look at policy priorities in the country.

To be able to push forward with the wider industrial programs of the government, it is necessary to relax prices, to allow the development of production and improve material supply.

To be able to push forward with the wider industrial programs of the government, it is necessary to relax prices, to allow the development of production and improve material supply.

The Duterte administration has a window of opportunity here --- through the shift in rice policy reform from quantitative restrictions to imposing moderate tariffs on rice imports.

The Duterte administration has a window of opportunity here --- through the shift in rice policy reform from quantitative restrictions to imposing moderate tariffs on rice imports.

This will not only benefit the poor from a projected P8 (or 20 percent) per kilo decrease in milled rice prices -- it will also benefit the farmers in the long run through the tariff revenues that can help finance a rice development fund that can be co-managed by farmers’ groups and targeted to cushion the impact of competition on some farmers, while also increasing investments towards farm productivity for the vast majority of our 3 million rice farmers.

This will not only benefit the poor from a projected P8 (or 20 percent) per kilo decrease in milled rice prices -- it will also benefit the farmers in the long run through the tariff revenues that can help finance a rice development fund that can be co-managed by farmers’ groups and targeted to cushion the impact of competition on some farmers, while also increasing investments towards farm productivity for the vast majority of our 3 million rice farmers.

Additional beneficiaries from more affordable food prices, include poor families and the vast majority of workers who are suffering from shrinkflation right now. And if this measure also convinces workers that their wages can be increased in real terms, instead of simply nominally, then this could also help preserve the wage competitiveness of our industries and help prolong our industrial push.

Additional beneficiaries from more affordable food prices, include poor families and the vast majority of workers who are suffering from shrinkflation right now. And if this measure also convinces workers that their wages can be increased in real terms, instead of simply nominally, then this could also help preserve the wage competitiveness of our industries and help prolong our industrial push.

It is critical that our policymakers focus on addressing the root causes of inflation on the supply side; and rice plays a key part in the inflation story.

It is critical that our policymakers focus on addressing the root causes of inflation on the supply side; and rice plays a key part in the inflation story.

We can fix our food security while mitigating pressure to increase wages through a well-implemented rice tariffication and rice sector investments. This solution has been staring us in the face for the last 20 years now.

We can fix our food security while mitigating pressure to increase wages through a well-implemented rice tariffication and rice sector investments. This solution has been staring us in the face for the last 20 years now.

(Ronald Mendoza is Dean and Associate Professor of Economics at the Ateneo School of Government (ASOG) and Ayn Torres is an economist at ASOG. The authors thank Jerik Cruz of the Ateneo Policy Center for the research assistance. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Ateneo de Manila University.)

(Ronald Mendoza is Dean and Associate Professor of Economics at the Ateneo School of Government (ASOG) and Ayn Torres is an economist at ASOG. The authors thank Jerik Cruz of the Ateneo Policy Center for the research assistance. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Ateneo de Manila University.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT