Close to a decade later, has Filipino food actually become “the next best thing”? | ABS-CBN

ADVERTISEMENT

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

Close to a decade later, has Filipino food actually become “the next best thing”?

Close to a decade later, has Filipino food actually become “the next best thing”?

Ige Ramos

Published Dec 15, 2019 04:02 PM PHT

|

Updated Dec 19, 2019 11:19 AM PHT

December is the last month in the tumultuous 2010s, a decade that saw the rise of new political heroes and villains, a changing of the guard in different sectors of society, the growing concern for climate change taking a more desperate turn, and an unending cacophony of opinionated people screaming into the Facebook void. In "The Last 10 Years," a series of pieces scattered over these last 30 days, we look back at what happened to try to figure out what comes next.

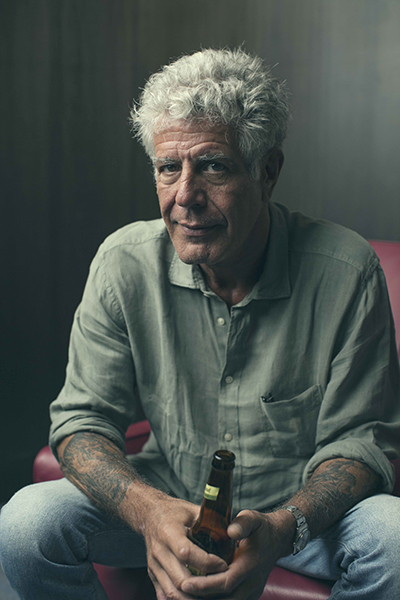

The last ten years have been an exciting time for Philippine cuisine. But have we created a dent in the culinary global stage yet? Does the 2012 prediction of Bizarre Foods’ Andrew Zimmern that Filipino food was going to be “the next best thing” hold water? When Anthony Bourdain visited the Philippines for No Reservations in 2009, was that the trigger that set off the hysteria that Filipino food is trendy by way of lechon and sisig?

The last ten years have been an exciting time for Philippine cuisine. But have we created a dent in the culinary global stage yet? Does the 2012 prediction of Bizarre Foods’ Andrew Zimmern that Filipino food was going to be “the next best thing” hold water? When Anthony Bourdain visited the Philippines for No Reservations in 2009, was that the trigger that set off the hysteria that Filipino food is trendy by way of lechon and sisig?

But do we really need this validation, or worse, do we want Filipino food to be trendy? These are the questions that always play on my mind.

But do we really need this validation, or worse, do we want Filipino food to be trendy? These are the questions that always play on my mind.

Time and time again, the international media asks why Filipino food has failed to gain the same popularity as Chinese, Japanese, or Thai cuisine. The answer is actually very simple. Living in an archipelago of more than 7,000 islands while speaking more than 80 languages, ours is not a homogenous culture. We can’t really compare our food to countries with monolithic cultures. Instead, we should celebrate our heterogeneity by acknowledging the diversity of our regional cuisine.

Time and time again, the international media asks why Filipino food has failed to gain the same popularity as Chinese, Japanese, or Thai cuisine. The answer is actually very simple. Living in an archipelago of more than 7,000 islands while speaking more than 80 languages, ours is not a homogenous culture. We can’t really compare our food to countries with monolithic cultures. Instead, we should celebrate our heterogeneity by acknowledging the diversity of our regional cuisine.

Triggering factors

Triggering factors

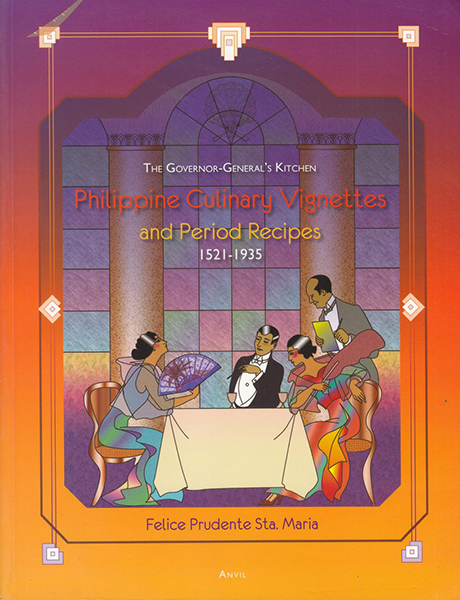

Long before Bourdain and Zimmern came onto the scene, Anvil Publishing in 2006, published The Governor-General’s Kitchen: Philippine Culinary Vignettes and Period Recipes 1521-1935 by Filipino food historian, Felice Prudente Sta. Maria. Although Doreen Gamboa Fernandez and Gilda Cordero Fernando came before her and wrote countless essays and tomes on Philippine food history, the primary aim of Sta. Maria’s book is to contextualize Philippine food history into digestible chapters so the readers may have a deeper understanding of Philippine Gastronomy.

Long before Bourdain and Zimmern came onto the scene, Anvil Publishing in 2006, published The Governor-General’s Kitchen: Philippine Culinary Vignettes and Period Recipes 1521-1935 by Filipino food historian, Felice Prudente Sta. Maria. Although Doreen Gamboa Fernandez and Gilda Cordero Fernando came before her and wrote countless essays and tomes on Philippine food history, the primary aim of Sta. Maria’s book is to contextualize Philippine food history into digestible chapters so the readers may have a deeper understanding of Philippine Gastronomy.

ADVERTISEMENT

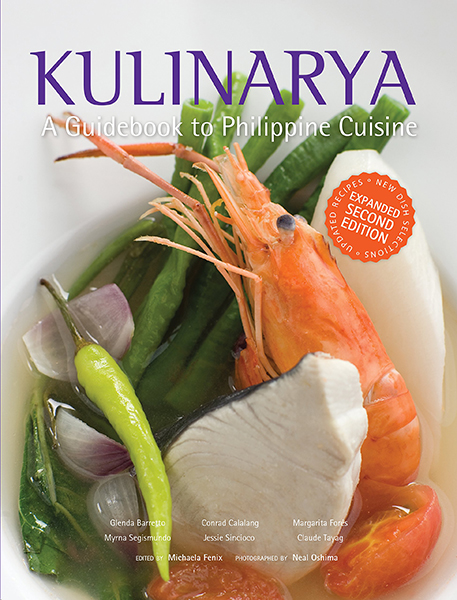

It was followed in 2008 by Kulinarya: A Guidebook to Philippine Cuisine, wherein six Filipino chefs and restaurateurs: Glenda Barretto, Conrad Calalang, Margarita Forés, Myrna Segismundo, Jessie Sincioco, and Claude Tayag, formed an alliance with Michaela Fenix as editor to carefully select recipes from regional to classic dishes that best represent the Philippine culinary canon. Seven years later in 2015, these chefs became the core group of Madrid Fusión Manila.

It was followed in 2008 by Kulinarya: A Guidebook to Philippine Cuisine, wherein six Filipino chefs and restaurateurs: Glenda Barretto, Conrad Calalang, Margarita Forés, Myrna Segismundo, Jessie Sincioco, and Claude Tayag, formed an alliance with Michaela Fenix as editor to carefully select recipes from regional to classic dishes that best represent the Philippine culinary canon. Seven years later in 2015, these chefs became the core group of Madrid Fusión Manila.

In a parallel universe, New York City in 2006, Amy Besa and Romy Dorotan fulfilled a life-long dream of writing a Filipino cookbook eleven years after their restaurant Cendrillon opened in Manhattan’s Soho. Memories of Philippine Kitchens, Stories and Recipes from Far and Near, was Besa and Dorotan’s love letter to the Filipino diaspora and Philippine cuisine’s calling card to America.

In a parallel universe, New York City in 2006, Amy Besa and Romy Dorotan fulfilled a life-long dream of writing a Filipino cookbook eleven years after their restaurant Cendrillon opened in Manhattan’s Soho. Memories of Philippine Kitchens, Stories and Recipes from Far and Near, was Besa and Dorotan’s love letter to the Filipino diaspora and Philippine cuisine’s calling card to America.

Since English is the language of Filipino food, th e transference of information during the last decade has been faster than ever.

Since English is the language of Filipino food, th e transference of information during the last decade has been faster than ever.

Second- and third-generation Filipino-American chefs and cooks yearning to understand their cultural singularity, look to Besa and Dorotan for inspiration. They see the couple as the embodiment of their aspiration because they were brave and pioneering, bewildered yet determined, in establishing a Philippine culinary outpost thousands of miles away from home. For them, this was an American dream fulfilled and this fact of history cannot be easily erased from our collective consciousness.

Second- and third-generation Filipino-American chefs and cooks yearning to understand their cultural singularity, look to Besa and Dorotan for inspiration. They see the couple as the embodiment of their aspiration because they were brave and pioneering, bewildered yet determined, in establishing a Philippine culinary outpost thousands of miles away from home. For them, this was an American dream fulfilled and this fact of history cannot be easily erased from our collective consciousness.

Cacophony of voices

Cacophony of voices

With the exception of Philippine major franchisees and a handful of mom-and-pop operated eateries, or restaurants bearing the “mixed-bag” Asian hodgepodge, catering mostly to the diaspora, there were no mainstream Filipino restaurants in the United States in the mid-1990’s.

With the exception of Philippine major franchisees and a handful of mom-and-pop operated eateries, or restaurants bearing the “mixed-bag” Asian hodgepodge, catering mostly to the diaspora, there were no mainstream Filipino restaurants in the United States in the mid-1990’s.

Cendrillon and eventually Purple Yam changed all that as they became the drumbeater for Filipino food culture. By the end of 2010, a plethora of restaurants bearing the convenient label “Asian fusion,” “Pan-Asian,” and “Asian soul food” and sneaking in Filipino menus on the side, started to mushroom all over America.

Cendrillon and eventually Purple Yam changed all that as they became the drumbeater for Filipino food culture. By the end of 2010, a plethora of restaurants bearing the convenient label “Asian fusion,” “Pan-Asian,” and “Asian soul food” and sneaking in Filipino menus on the side, started to mushroom all over America.

Social media became a game changer as the cult of the celebrity chef, TV reality show deals, and investors with deep pockets were the order of the day. It was an opportunity for the brave and the bold to shine.

Social media became a game changer as the cult of the celebrity chef, TV reality show deals, and investors with deep pockets were the order of the day. It was an opportunity for the brave and the bold to shine.

Dale Talde’s irreverent Proudly Inauthentic Filipino debut cookbook was one of the early incarnations of what the new generation of Fil-Am chefs in America is cooking. Like most Fil-Ams, he is constantly searching for an alternative identity in forming new concepts for his restaurants. He was one of the early celebrity chefs who enjoyed great popularity following his appearance on Top Chef in 2008.

Dale Talde’s irreverent Proudly Inauthentic Filipino debut cookbook was one of the early incarnations of what the new generation of Fil-Am chefs in America is cooking. Like most Fil-Ams, he is constantly searching for an alternative identity in forming new concepts for his restaurants. He was one of the early celebrity chefs who enjoyed great popularity following his appearance on Top Chef in 2008.

One of the more promising Fil-Am chefs in 2010 was Paul Qui. Based in Austin, Texas, he ran two restaurants: his eponymous Qui and East Side King. He was propelled to fame after winning Top Chef in 2011, the James Beard Award for Best Chef, Southwest in 2012, and a host of other media accolades. However, in 2016, a series of events brought his career to a temporary halt.

One of the more promising Fil-Am chefs in 2010 was Paul Qui. Based in Austin, Texas, he ran two restaurants: his eponymous Qui and East Side King. He was propelled to fame after winning Top Chef in 2011, the James Beard Award for Best Chef, Southwest in 2012, and a host of other media accolades. However, in 2016, a series of events brought his career to a temporary halt.

In 2009, Fil-Am restaurateur Nicole Ponseca, together with chef Miguel Trinidad, started a pop-up around Manhattan that gave birth to Maharlika (which just closed this week) and Jeepney Gastropub. In 2017, they embarked on a food tour of the Philippines and produced I Am a Filipino: And This Is How We Cook, which was a 2019 James Beard Award finalist.

In 2009, Fil-Am restaurateur Nicole Ponseca, together with chef Miguel Trinidad, started a pop-up around Manhattan that gave birth to Maharlika (which just closed this week) and Jeepney Gastropub. In 2017, they embarked on a food tour of the Philippines and produced I Am a Filipino: And This Is How We Cook, which was a 2019 James Beard Award finalist.

Learning from the people who came before him, fellow Fil-Am Tom Cunanan is a cautious and observant chef of Philippine cuisine. Gaining experience from restaurants across Washington DC and with his undying love for his mother, he began documenting her recipes that were to become the basis for his catering business.

Learning from the people who came before him, fellow Fil-Am Tom Cunanan is a cautious and observant chef of Philippine cuisine. Gaining experience from restaurants across Washington DC and with his undying love for his mother, he began documenting her recipes that were to become the basis for his catering business.

Meeting like-minded restaurateurs, Cunanan opened Bad Saint in the Columbia Heights neighbourhood of Washington, DC in 2015. Soon after, the praises came one after another as a testament to his hard work and distinctive food. After being a finalist in 2017 and 2018, Cunanan finally bagged the 2019 James Beard Award for Best Chef, Mid-Atlantic.

Meeting like-minded restaurateurs, Cunanan opened Bad Saint in the Columbia Heights neighbourhood of Washington, DC in 2015. Soon after, the praises came one after another as a testament to his hard work and distinctive food. After being a finalist in 2017 and 2018, Cunanan finally bagged the 2019 James Beard Award for Best Chef, Mid-Atlantic.

The enablers

The enablers

In 2009, towards the end of the term of US President George W. Bush, Filipina-American chef Cristeta Comerford was endorsed by former First Lady Laura Bush to the Obamas to be retained in the White House kitchen. She was eventually made executive chef by the then First Lady, Michele Obama. Comerford was the quiet force that may have sparked the Filipino food consciousness in the nation’s capital.

In 2009, towards the end of the term of US President George W. Bush, Filipina-American chef Cristeta Comerford was endorsed by former First Lady Laura Bush to the Obamas to be retained in the White House kitchen. She was eventually made executive chef by the then First Lady, Michele Obama. Comerford was the quiet force that may have sparked the Filipino food consciousness in the nation’s capital.

Sam Sifton, the food writer and editor of The New York Times was a natural vector in delivering Besa and Dorotan’s message via NYT Cooking, while his Fil-Am colleague Ligaya Mishan and chef and cultural maven Angela Dimayuga continue to strengthen the Filipino food discourse in America.

Sam Sifton, the food writer and editor of The New York Times was a natural vector in delivering Besa and Dorotan’s message via NYT Cooking, while his Fil-Am colleague Ligaya Mishan and chef and cultural maven Angela Dimayuga continue to strengthen the Filipino food discourse in America.

By co-presenting the Madrid Fusión Manila in 2015, 2016, and 2017 and the World Street Food Congress in 2016 and 2017, which was jointly run by the Tourism Promotions Board, the enablers of the promotion of Philippine cuisine overseas in the last decade were former Secretary of Tourism Ramon Jimenez and the then Department of Agriculture Undersecretary Berna Romulo-Puyat.

By co-presenting the Madrid Fusión Manila in 2015, 2016, and 2017 and the World Street Food Congress in 2016 and 2017, which was jointly run by the Tourism Promotions Board, the enablers of the promotion of Philippine cuisine overseas in the last decade were former Secretary of Tourism Ramon Jimenez and the then Department of Agriculture Undersecretary Berna Romulo-Puyat.

Pacita “Chit” Juan took the helm in running Slow Food Philippines by helping to establish communities all over the country with the Ark of Taste that identifies indigenous endangered ingredients. The Philippines had a strong presence in Slow Food’s Terra Madre and Salone del Gusto in Turin, Italy in 2016 and 2018, featuring Asia’s Best Female Chef for 2016, Margarita Forés.

Pacita “Chit” Juan took the helm in running Slow Food Philippines by helping to establish communities all over the country with the Ark of Taste that identifies indigenous endangered ingredients. The Philippines had a strong presence in Slow Food’s Terra Madre and Salone del Gusto in Turin, Italy in 2016 and 2018, featuring Asia’s Best Female Chef for 2016, Margarita Forés.

Jam Melchor handled the Philippine branch of Slow Food Youth Network, giving him the opportunity to show his mettle as the only Filipino chef to cook at the University of Gastronomic Sciences in Italy, while being the convener of the Philippine Culinary Heritage Movement.

Jam Melchor handled the Philippine branch of Slow Food Youth Network, giving him the opportunity to show his mettle as the only Filipino chef to cook at the University of Gastronomic Sciences in Italy, while being the convener of the Philippine Culinary Heritage Movement.

Food historian Felice Prudente Sta. Maria and Sau del Rosario participated in IV Foro Mundial de la Gastronomía Mexicana 2016, showcasing the culinary confluence between Mexico and the Philippines. Borja Sanchez, a social anthropologist from Mexico, meanwhile delivered a lecture at the Ateneo de Manila University on her dissertation on the Filipino adobo as pre-Hispanic. Chef Myke “Tatung” Sarthou wowed the audience in the 2017 edition of Madrid Fusión in Spain, and again, Sau del Rosario and JP Anglo were the featured Filipino chefs at the San Sebastian Gastronomika, also in Spain in 2019.

Food historian Felice Prudente Sta. Maria and Sau del Rosario participated in IV Foro Mundial de la Gastronomía Mexicana 2016, showcasing the culinary confluence between Mexico and the Philippines. Borja Sanchez, a social anthropologist from Mexico, meanwhile delivered a lecture at the Ateneo de Manila University on her dissertation on the Filipino adobo as pre-Hispanic. Chef Myke “Tatung” Sarthou wowed the audience in the 2017 edition of Madrid Fusión in Spain, and again, Sau del Rosario and JP Anglo were the featured Filipino chefs at the San Sebastian Gastronomika, also in Spain in 2019.

Cuisine interrupted

Cuisine interrupted

There is a problem in how we define Filipino food. While there are efforts in promoting our cuisine overseas, do we stick to the traditional cooking conventions or is there room for innovation?

There is a problem in how we define Filipino food. While there are efforts in promoting our cuisine overseas, do we stick to the traditional cooking conventions or is there room for innovation?

Doreen Fernandez’s tried and tested recipe on how to define Filipino food does not ask, “What is Filipino food?” but rather questions, “How it becomes Filipino?” Adding to that statement, the popular historian Ambeth Ocampo mentioned in one of his lectures that the Philippines is a young nation with a long, ancient history with colonial disruption, which could be a clue as to how we define our food. And with our fragmented geography and hundreds of languages, how do we define a national taste?

Doreen Fernandez’s tried and tested recipe on how to define Filipino food does not ask, “What is Filipino food?” but rather questions, “How it becomes Filipino?” Adding to that statement, the popular historian Ambeth Ocampo mentioned in one of his lectures that the Philippines is a young nation with a long, ancient history with colonial disruption, which could be a clue as to how we define our food. And with our fragmented geography and hundreds of languages, how do we define a national taste?

To paraphrase Fernandez, do we dare to ask, “How food becomes Fil-Am?” and how it is related to our culture that Fil-Am food is an integral part of the Filipino culinary canon? Fil-Am food is really part of our culture. The creations of the chefs and restaurateurs mentioned are a deliberate and purposeful effort to connect to the Motherland.

To paraphrase Fernandez, do we dare to ask, “How food becomes Fil-Am?” and how it is related to our culture that Fil-Am food is an integral part of the Filipino culinary canon? Fil-Am food is really part of our culture. The creations of the chefs and restaurateurs mentioned are a deliberate and purposeful effort to connect to the Motherland.

Food is a cultural artefact, invested with themes and inspiration that emanates from the home country. Combined with the chef's creativity, cultural bias, intent, and cooking techniques, it is undeniably, unmistakably Filipino.

Food is a cultural artefact, invested with themes and inspiration that emanates from the home country. Combined with the chef's creativity, cultural bias, intent, and cooking techniques, it is undeniably, unmistakably Filipino.

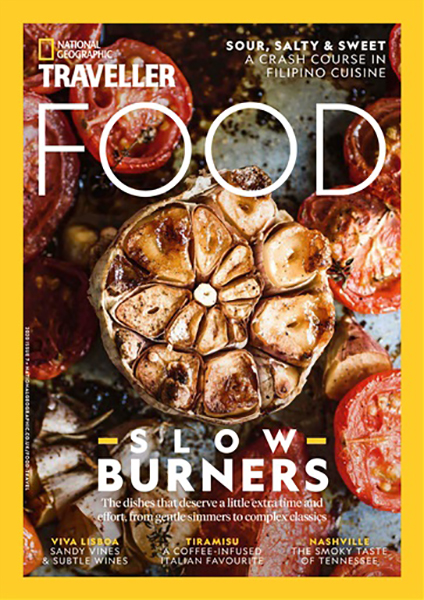

We have come full circle since the unlikely messiah of Filipino food, Andrew Zimmern, first prophesied it as the “next big thing” through the lens of “bizarre” food. But when a magazine focusing on strong narratives and authentic food experiences publishes an article on Filipino food, one really must take it seriously. Case in point is National Geographic Traveller Food with “The Rise and Rise of Filipino Food” in its May 2019 issue.

We have come full circle since the unlikely messiah of Filipino food, Andrew Zimmern, first prophesied it as the “next big thing” through the lens of “bizarre” food. But when a magazine focusing on strong narratives and authentic food experiences publishes an article on Filipino food, one really must take it seriously. Case in point is National Geographic Traveller Food with “The Rise and Rise of Filipino Food” in its May 2019 issue.

As the year comes to an end, the magazine followed up with a banner story for its January 2020 issue: “Sour, Salty and Sweet, Crash Course in Filipino Cuisine,” focusing on Manila as provenance, with insights from chefs Josh Boutwood and Jordy Navarra, the people in the forefront of contemporary Filipino food today.

As the year comes to an end, the magazine followed up with a banner story for its January 2020 issue: “Sour, Salty and Sweet, Crash Course in Filipino Cuisine,” focusing on Manila as provenance, with insights from chefs Josh Boutwood and Jordy Navarra, the people in the forefront of contemporary Filipino food today.

I’m relieved that National Geographic went beyond the balut (duck’s egg embryo), tamilok (shipworms), and kamaru (field crickets). But then again, we must thank Andrew Zimmern for even noticing in the first place.

I’m relieved that National Geographic went beyond the balut (duck’s egg embryo), tamilok (shipworms), and kamaru (field crickets). But then again, we must thank Andrew Zimmern for even noticing in the first place.

Anthony Bourdain photo by Pat Mateo for Metro Society

Tom Cunanan photos by Jar Concengco

Purple Yam photos by JC Inocian for FOOD Magazine

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT