The Conrad Calalang touch: how this food-loving Bulakeño shaped Manila’s dining scene

ADVERTISEMENT

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

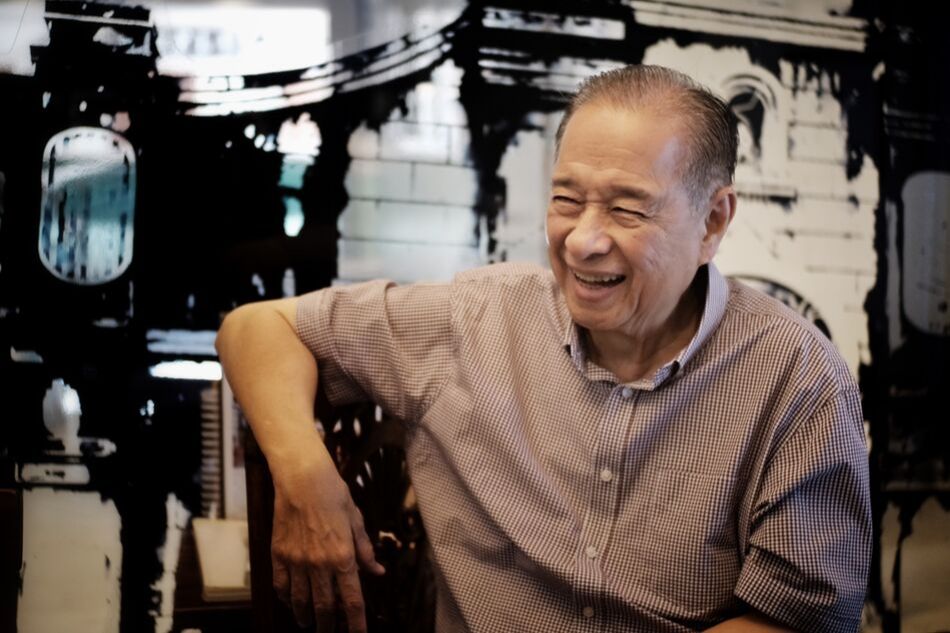

The Conrad Calalang touch: how this food-loving Bulakeño shaped Manila’s dining scene

Michaela Fenix

Published Sep 13, 2019 05:52 PM PHT

Pimbrera. How many young people today know the word?

Pimbrera. How many young people today know the word?

For people of a certain age, it conjures the lunchbox of their childhood, stacked food containers held together by a handle, sometimes made of ordinary aluminum, or high-end stainless steel, maybe enamel in artsy sunshine colors.

For people of a certain age, it conjures the lunchbox of their childhood, stacked food containers held together by a handle, sometimes made of ordinary aluminum, or high-end stainless steel, maybe enamel in artsy sunshine colors.

In other parts of the world, the pimbrera is called a tiffin, although each country that has them—Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, India, Pakistan, even Germany—calls them by their own local names.

In other parts of the world, the pimbrera is called a tiffin, although each country that has them—Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, India, Pakistan, even Germany—calls them by their own local names.

You may also like:

You may also like:

Conrad Calalang decided to call his mostly take-out food place “Pimbrera ng Barasoain” just in case you didn’t know that he is from Bulacan where the famous Barasoain Church is located. But the frozen food he sells are now contained in plastic containers, not pimbreras, neatly arranged in freezers, ready to be brought home.

Conrad Calalang decided to call his mostly take-out food place “Pimbrera ng Barasoain” just in case you didn’t know that he is from Bulacan where the famous Barasoain Church is located. But the frozen food he sells are now contained in plastic containers, not pimbreras, neatly arranged in freezers, ready to be brought home.

ADVERTISEMENT

Calalang says he isn’t the first one to expect that homes today will no longer have cooks in their line-up of household help. Big houses near his business (located in exclusive villages like Forbes, Dasmariñas, and the greater Makati) are now empty nests and their senior residents don’t need a lot of food. Their children who used to reside in those big houses opt to stay in condominiums with no room for help like a cook.

Calalang says he isn’t the first one to expect that homes today will no longer have cooks in their line-up of household help. Big houses near his business (located in exclusive villages like Forbes, Dasmariñas, and the greater Makati) are now empty nests and their senior residents don’t need a lot of food. Their children who used to reside in those big houses opt to stay in condominiums with no room for help like a cook.

It is Calalang’s astute culinary business sense that made him open Pimbrera in 2012, as well as the other restaurants that came before. These restaurants, although they are no more, were considered among Manila’s most popular restaurants during their heyday. He began with the then still new concept, Mongolian Grill, in 1986 at the Mile Long Center in Makati where, because it was always full, he opened a second one at the same venue a few months after. His interest in Italian cooking moved him to open Intermezzo at the still new Greenbelt in 1992. A year after, it was his Filipino restaurant Barasoain also at the Mile Long Center, as well as another Italian, Seasons, at Greenbelt. At the time, one could describe his restaurants as trendy, even Barasoain, because it introduced a different way to present Filipino cooking.

It is Calalang’s astute culinary business sense that made him open Pimbrera in 2012, as well as the other restaurants that came before. These restaurants, although they are no more, were considered among Manila’s most popular restaurants during their heyday. He began with the then still new concept, Mongolian Grill, in 1986 at the Mile Long Center in Makati where, because it was always full, he opened a second one at the same venue a few months after. His interest in Italian cooking moved him to open Intermezzo at the still new Greenbelt in 1992. A year after, it was his Filipino restaurant Barasoain also at the Mile Long Center, as well as another Italian, Seasons, at Greenbelt. At the time, one could describe his restaurants as trendy, even Barasoain, because it introduced a different way to present Filipino cooking.

Take the Pinalutong na Pla Pla or fried big tilapia. Calalang said he copied how it was done in Bali, the fish sliced in such a way as to look like it has wings. And then Larry J. Cruz asked him if he could copy the dish for his own restaurant at the time, Larry’s at Greenbelt 1, which has proven to be a hit as Binukadkad na Plapla at many of the present-day restaurants of the LJC Group.

Take the Pinalutong na Pla Pla or fried big tilapia. Calalang said he copied how it was done in Bali, the fish sliced in such a way as to look like it has wings. And then Larry J. Cruz asked him if he could copy the dish for his own restaurant at the time, Larry’s at Greenbelt 1, which has proven to be a hit as Binukadkad na Plapla at many of the present-day restaurants of the LJC Group.

The restaurant scene then was not as expanded as it is now and everyone in the business knew each other. At the Mile Long Cener, Calalang would take lunch at Add Lim’s early Thai restaurant, Flavors and Spices. Even cooks would move from one restaurant to the other and he remembers how the Filipino “number 2 cook of Nora Daza at Au Bon Vivant” also worked at Seasons. On a trip to Milan where his hosts brought him to a noted French restaurant, he was surprised to see that same cook introduced as the chef.

The restaurant scene then was not as expanded as it is now and everyone in the business knew each other. At the Mile Long Cener, Calalang would take lunch at Add Lim’s early Thai restaurant, Flavors and Spices. Even cooks would move from one restaurant to the other and he remembers how the Filipino “number 2 cook of Nora Daza at Au Bon Vivant” also worked at Seasons. On a trip to Milan where his hosts brought him to a noted French restaurant, he was surprised to see that same cook introduced as the chef.

But the better story is not Calalang’s business sense but how he preserves traditional Filipino cooking. According to the published menu, Pimbrera shares, “our Lola’s… secret and subtle touches that make simple home-cooked meals so memorable and mouth-watering.”

But the better story is not Calalang’s business sense but how he preserves traditional Filipino cooking. According to the published menu, Pimbrera shares, “our Lola’s… secret and subtle touches that make simple home-cooked meals so memorable and mouth-watering.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Those words describe exactly what Pimbrera food remind you of—flavors that you no longer get to taste. It’s not because some of what is offered may no longer be cooked at one’s house or be had in today’s restaurants. These dishes are the result of slow cooking and using the best ingredients that end up, for lack of a better word, malinamnam, which has a deeper meaning than mere “tasty.” One Filipino chef described this as “nagaagaw sa lasa,” different flavors clamoring for attention, each one distinct and yet melding together.

Those words describe exactly what Pimbrera food remind you of—flavors that you no longer get to taste. It’s not because some of what is offered may no longer be cooked at one’s house or be had in today’s restaurants. These dishes are the result of slow cooking and using the best ingredients that end up, for lack of a better word, malinamnam, which has a deeper meaning than mere “tasty.” One Filipino chef described this as “nagaagaw sa lasa,” different flavors clamoring for attention, each one distinct and yet melding together.

This is how the Pakam tasted at first bite. Pakam is a Bulacan dish, a stew originally of talunan or the losing fighting cock. For years, I had begged Calalang to cook the dish after he described it during one of our conversations. What a great thing that Pimbrera now offers it. It is simple cooking of sautéing the chicken first with ginger, garlic, onion, and tomatoes; seasoning with fish sauce and vinegar, laurel, salt and pepper; then adding chicken liver with water to complete the cooking. It was subtly tasty, no overpowering flavor like the too salty, too hot, too sweet food today. But one can imagine in the old days that the fighting cock must have been tenderized first by boiling.

This is how the Pakam tasted at first bite. Pakam is a Bulacan dish, a stew originally of talunan or the losing fighting cock. For years, I had begged Calalang to cook the dish after he described it during one of our conversations. What a great thing that Pimbrera now offers it. It is simple cooking of sautéing the chicken first with ginger, garlic, onion, and tomatoes; seasoning with fish sauce and vinegar, laurel, salt and pepper; then adding chicken liver with water to complete the cooking. It was subtly tasty, no overpowering flavor like the too salty, too hot, too sweet food today. But one can imagine in the old days that the fighting cock must have been tenderized first by boiling.

It was the same with the Pinatisang Manok, another Bulacan chicken dish that Nora Daza included in her books Let’s Cook with Nora and A Culinary Life. She obtained the recipe from Calalang’s father, Don Alfonso, who was considered a gourmet. But it is also known by family and friends that it was the cooking of Calalang’s mother that trained his taste buds.

It was the same with the Pinatisang Manok, another Bulacan chicken dish that Nora Daza included in her books Let’s Cook with Nora and A Culinary Life. She obtained the recipe from Calalang’s father, Don Alfonso, who was considered a gourmet. But it is also known by family and friends that it was the cooking of Calalang’s mother that trained his taste buds.

Calalang chose for us to try other traditional dishes from his long menu. We tasted the Bangus en Tocho (milkfish cooked with tomatoes, tahure or fermented bean cake, and salted black beans), the Bopis (pork lungs and heart), and the Quail Adobo. I expected that my generation would illicit such favorable reviews on these “old” dishes. But the next generation on tasting these unfamiliar dishes looked surprised at how good and different the flavors were and wondered how they could taste so good.

Calalang chose for us to try other traditional dishes from his long menu. We tasted the Bangus en Tocho (milkfish cooked with tomatoes, tahure or fermented bean cake, and salted black beans), the Bopis (pork lungs and heart), and the Quail Adobo. I expected that my generation would illicit such favorable reviews on these “old” dishes. But the next generation on tasting these unfamiliar dishes looked surprised at how good and different the flavors were and wondered how they could taste so good.

What is cooked today, laments Calalang, isn’t as good as what was cooked before. Because today one can’t have the prime ingredients available then—the Paombong vinegar, the best patis, even the bangus direct from the best fishponds. And especially for the Pakam, one can no longer get the chicken blood formed into blocks with rice grains. One wonders that if everything was back to what it was, what flavors then are we missing?

What is cooked today, laments Calalang, isn’t as good as what was cooked before. Because today one can’t have the prime ingredients available then—the Paombong vinegar, the best patis, even the bangus direct from the best fishponds. And especially for the Pakam, one can no longer get the chicken blood formed into blocks with rice grains. One wonders that if everything was back to what it was, what flavors then are we missing?

ADVERTISEMENT

Conrad Calalang was one of the chefs asked to be part of the book Kulinarya: A Guidebook to Philippine Cuisine. It was precisely because of his knowledge of traditional cooking that one of the authors, Via Mare’s Glenda Barretto, invited him to contribute recipes and help in making the book. While none of the chefs put their names to particular recipes, a reader who knows Calalang is sure that the Pochero with the two sauces—tomato and berenjena or eggplant—is from him. It is there on the Pimbrera menu, requiring advance order, just like the cochinillo, deceptively small, crunchy, so tasty, and eliciting guilty feelings with every bite.

Conrad Calalang was one of the chefs asked to be part of the book Kulinarya: A Guidebook to Philippine Cuisine. It was precisely because of his knowledge of traditional cooking that one of the authors, Via Mare’s Glenda Barretto, invited him to contribute recipes and help in making the book. While none of the chefs put their names to particular recipes, a reader who knows Calalang is sure that the Pochero with the two sauces—tomato and berenjena or eggplant—is from him. It is there on the Pimbrera menu, requiring advance order, just like the cochinillo, deceptively small, crunchy, so tasty, and eliciting guilty feelings with every bite.

Over crunchy cochinillo, we talked about where to get the best roasted suckling pig in Spain. Most Filipinos know El Botin in Madrid because the main asadors or roasters are Filipinos from Pampanga. He was told by these asadors that the cochinillo is half-cooked, then when ordered, is cooked through. But he was advised to order a cochinillo that is cooked through from the beginning. He also likes the cochinillo of Meson de Candido in Segovia. But the best for him is at the Asador Las Cubas in Avila.

Over crunchy cochinillo, we talked about where to get the best roasted suckling pig in Spain. Most Filipinos know El Botin in Madrid because the main asadors or roasters are Filipinos from Pampanga. He was told by these asadors that the cochinillo is half-cooked, then when ordered, is cooked through. But he was advised to order a cochinillo that is cooked through from the beginning. He also likes the cochinillo of Meson de Candido in Segovia. But the best for him is at the Asador Las Cubas in Avila.

Because he has been able to try so many restaurants around the world, friends ask him for recommendations before they travel. He said with a chuckle that you can be sure that only the best are included.

Because he has been able to try so many restaurants around the world, friends ask him for recommendations before they travel. He said with a chuckle that you can be sure that only the best are included.

It is Calalang’s constant interest in food—how to cook it and where to get the best—that keeps him traveling and studying. Before the interview, he had just arrived from Valencia in Spain where he studied how to make the paella. The secret, he said, is in the brodo, using the Italian word for broth, instead of caldo.

It is Calalang’s constant interest in food—how to cook it and where to get the best—that keeps him traveling and studying. Before the interview, he had just arrived from Valencia in Spain where he studied how to make the paella. The secret, he said, is in the brodo, using the Italian word for broth, instead of caldo.

Italian food, after all, is his first love. He studied at the Scuola di Medici in Florence before he opened Intermezzo and Seasons. Many of those Italian dishes have found their way to The Last Chukker, the members-only restaurant run by his daughter Vanna inside the Manila Polo Club. It is where diners can still enjoy the original Decadent Chocolate Cake, with Calalang credited as first introducing this now classic dessert to the country. He has also branched out into Japanese with the members-only Nanten, also at the Manila Polo Club, which is the result of his studies in that cuisine and his regular visits to the country.

Italian food, after all, is his first love. He studied at the Scuola di Medici in Florence before he opened Intermezzo and Seasons. Many of those Italian dishes have found their way to The Last Chukker, the members-only restaurant run by his daughter Vanna inside the Manila Polo Club. It is where diners can still enjoy the original Decadent Chocolate Cake, with Calalang credited as first introducing this now classic dessert to the country. He has also branched out into Japanese with the members-only Nanten, also at the Manila Polo Club, which is the result of his studies in that cuisine and his regular visits to the country.

ADVERTISEMENT

So casually I asked where he is going next, not really expecting an answer right away. Nova Scotia, he said, because it has great seafood. But the place he really wants to visit again is Greece and Crete. And his smile stops you from asking why because there will be more time required for him to enumerate, and we were taking up too much of his time already.

So casually I asked where he is going next, not really expecting an answer right away. Nova Scotia, he said, because it has great seafood. But the place he really wants to visit again is Greece and Crete. And his smile stops you from asking why because there will be more time required for him to enumerate, and we were taking up too much of his time already.

Pimbrera ng Barasoain, San Antonio Plaza, McKinley Road, Makati City, (02) 775-4128

Photos by Chris Clemente

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT