War on drugs:

The unheard stories

First of a series

ABS-CBN Investigative and Research Group

ABS-CBN News Digital Media

It was about 11 p.m. Tuesday, July 5, when a team of at least eight men in motorcycles swooped down on the barong-barong of Roberto Dominguez in Poblacion, Caloocan City. He was sleeping beside his one-year-old daughter.

The heavily armed men moved swiftly into his room, woke him up, and aimed their long firearms at Dominguez. Bewildered, he told the men: "Ser, wag niyo naman ho akong barilin kasi andito anak ko."

Teresita Dominguez, 58, mother of

Roberto Dominguez

This was how Dominguez’s mother, Teresita Dominguez, recalled how her son died in the hands of the policemen. He was begging for his life until she and her neighbors heard some four gunshots from the room, she said.

On Wanted List

Teresita would learn later that the policemen gunned her son down on suspicion he was a drug peddler.

Dominguez, 40, was on a list prepared by Barangay 15 of suspected peddlers of prohibited drugs, she was told. Teresita admitted her son had been hooked in drugs and was charged with illegal possession of drugs in 2009.

Neighbor gave him away

A caller had informed the police that Dominguez was selling drugs to another man inside his home, one of the tightly-knit shanties located a few meters away from the railroad in the barangay, prompting the police operation.

In no time, the eight members of the Caloocan City Police Station Anti-Illegal Drugs unit, in full battle gear, arrived, inching through a labyrinth of dark alleys at around 11 p.m. looking for the house of Dominguez.

Jacqueline Celestine, wife of Dominguez,

and their child

Behold one’s child

Once they found the target, the men zoomed in, kicked the door twice to open it, and found a woman and a baby girl sleeping on the floor. They were Dominguez’s live-in partner and another daughter, one-month old.

They dragged her and the child outside the house without explanation. They rummaged through the room, throwing away anything they could get hold of—clothes, plates, tables, and chairs. They turned everything upside down. They found Dominguez and the first baby upstairs.

Next door, Dominguez’s mother heard her daughter-in-law and granddaughter crying and shouting. She walked closer, but policemen prevailed upon her.

“Misis wag na po kayo lumabas, madadamay kayo, isara niyo yung pinto, isara niyo,” she quoted one of them as telling her.

Behold one’s mother

Minutes later, a gunshot echoed through the neighborhood. Teresita was horrified. Was it her son? In between, she heard someone calling: “Nay! Aray ko nay! Aray ko!”

Her son has died, she was told later.

Her son died of multiple gunshot wounds. “Yung isa po dito, tagos po dito sa p’wet,” Teresita said, theorizing that the police fired upon her son while he was down on his knees. “Yung dibdib ng anak ko, hati ito. Ang laki ng sugat.”

By then, police came in and out of Dominguez’s door, and there emerged the dead man’s one-year-old daughter, wailing.

Teresita heard some more gunshots. She also heard something she couldn’t believe.

Son fought back

“Lumalaban ka pa ah! Tang ina mo ka buti hindi pumutok,” she heard another policeman talking.

Did my son fight back? How could he? He had no gun, she said.

Teresita and her daughter, Marites, had gone hysterical, drawing the ire of the police. Marites was brought inside the police car to silence her.

“Galit na galit ‘yung isang pulis kasi salita ng salita ‘yung anak ko,” Teresita said. “Sabi niya: ‘O, bakit kayo nagpapaputok dito? Maraming bata rito.’ Sabi naman nung isang pulis, ‘Putangina mo! ang ingay ingay mo! Posasan niyo nga yan.”

Dominguez was one of the 50 slain drug criminals whose cases an ABS-CBN Investigative and Research team revisited between August 1 and September 9.

The team interviewed police and barangay officials, and families, friends, neighbors of the 50 drug suspects killed in police operations in Metro Manila, Bulacan, Rizal, Laguna, and Cavite between May 10 and July 27.

Certified users, peddlers

Based on these interviews and police records, 46 of the 50 dead had been involved in illegal drugs, either as user or peddler, or both.

Thirty-one of them, including Dominguez, were included in the anti-drug watch list of the barangay and the police.

One victim’s involvement could not be determined because of conflicting statements of the family and the police.

Dying in sleep

But relatives of 43 of the 50 suspects said the dead did not fight back. Of the 43 slain victims, about 16, Dominguez among them, were heard begging for their lives before they were shot to death.

Many of these victims were even sleeping before they were killed, contrary to the police version that they were the subject of buy-bust operations.

Relatives of five other slain suspects made similar claims but could not provide supporting details.

Only 2 fought back

Only two of the 50 appeared to have clearly fought back—Brian Oliveros, 40, of Taguig City and George Oliveros, 36, of General Malvar, Cavite—if only because of the police casualties recorded, official police reports and witnesses showed. (The two Oliveroses were not related).

Collateral damage

The ABS-CBN team also located relatives of 13 other victims but they refused to grant a formal interview out of fear. Some have abandoned their homes for good for the same reason.

Families of at least three dead said their relatives were merely collateral damages in the war on drugs.

Male and poor

These were Julius Dizon, 25, of Muntinlupa City; Joel Galang, 30, of Calamba City, Laguna; and Jerome Garcia, 23, of Sta. Rosa City, Laguna. They were caught in the company of the police target at the time they were killed, their families and official records said.

Almost all of the victims were poor, lived in the slums and outskirts of the provinces. They were unemployed or last employed either as construction workers, drivers, or porters. Many were breadwinners, while some were providing a bit of support to their families. They were all male.

They had police record

Thirty of them had previous brushes with the law and been jailed, but were later released, according to their families: 17 of them were charged with drug related cases, eight with non-drug related cases, and five of them were charged with both drug and non-drug related crimes.

Duterte’s war

Thousands have been killed in President Duterte’s war on drugs since he decisively won in the May 9 elections. US President Barack Obama and UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, and local and international human rights groups have criticized the President, saying the war has violated the human rights of the drug suspects.

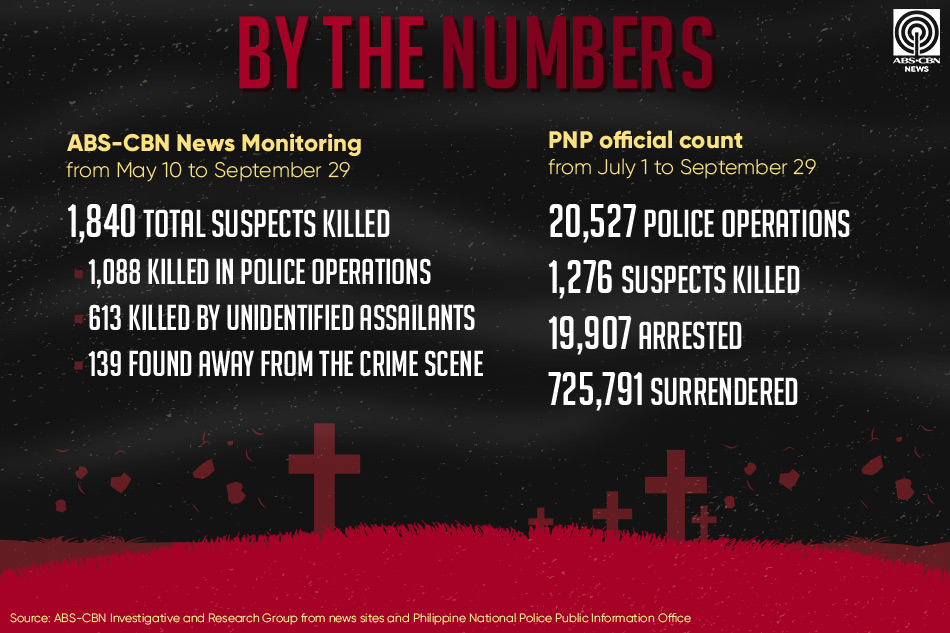

In the monitoring of the ABS-CBN Investigative and Research Group, a total of 1,756 have been killed from May 10 to September 26.

Of this number, 1,031 of these were killed in police operations, 592 were killed by unidentified assailants, and 133 bodies were found away from the crime scene.

But official figures were much higher, which means that there were many unreported and explained deaths on top of those reported in media.

2,500 die; 700,000 yield

As of September 18, the Philippine National Police has conducted 18,467 operations in the war on drugs nationwide.

About 714,803 have surrendered, clogging detention and rehabilitation centers, a phenomenon that even surprised the Duterte administration on the extent of the nationwide drug menace.

The PNP operations also resulted in the death of 1,140 drug suspects.

But outside the police operations, there were 1,571 other reported deaths as of September 14 that even the police could hardly explain; the deaths allegedly perpetrated either by so-called vigilantes or other members of drug syndicates eliminating people who might testify against them.

No warrant, no mercy

The ABS-CBN team’s investigation showed a seeming hallmark in the way the police conducted their operations, some of these bordered on the brutal and inhumane, if the families and witnesses were to be believed.

As pieced together by the ABS-CBN team, police operatives would arrive in target site, numbering anywhere between 10 and 30 men, some in plainclothes and masks, and barge inside a home without warning before shooting the victim. They showed no warrant, not even an iota of respect to the homeowner.

They were usually members of the police’s Station Anti-Illegal Drugs unit, Special Operations Task Group, and the Station Intelligence Branch.

Standard procedure

Even when the victim was with other people at the time of the operation, the authorities would forcibly pull all the people out of the house.

The police would not just contain the victim’s family, but also the whole community.

A policeman would guard each house to prevent the rest of the neighborhood from leaving their own homes.

But because the neighborhoods where the operations happened were mostly tightly-knit slums, residents would hear what was happening.

In many cases, they heard the police fired warning shots and shout at the victim as if he was resisting, before they would fire another round.

No signs of struggle

Witnesses said they did not hear any commotion or struggle and in several cases, the victims—like Roberto Dominguez—were heard surrendering or pleading for their lives right before they were killed.

“Sabi niya: ‘nay! Aray ko nay! Aray ko!’” Teresita said, wiping her tears. “Humingi pa ng saklolo yung anak ko bago namatay.”

In some cases, the police’s Scene of the Crime Operatives would arrive as fast as 15 minutes to as late as three hours—like in the case of Dominguez—to examine the crime scene and gather the pieces of evidence, ranging from packets of suspected methamphetamine hydrochloride, also known as shabu, to a .38-caliber revolver loaded with bullets, and fired cartridges.

All-too familiar tale

Dominguez had four shots: one in the hand and the belly, and two in the chest, Teresita said, showing pictures of her son’s body from the morgue.

Nearly all of the police records of 46 out of 50 victims obtained by ABS-CBN News narrated an all-too familiar scene: The drug suspect, after either sensing that he was transacting with a policeman or seeing an approaching policeman, would draw his gun and shoot, prompting the authorities to strike back, shoot him in the most vital body part, killing him instantly, reminiscent of several scenes in Erik Matti’s film On the Job showing the struggle between the police and a villain.

Death came in his sleep

A total of 29 victims were killed in buy-bust operations, where the police entrap the criminal in the act of committing an offense. There must be an initial contact between the poseur-buyer and the pusher, the offer to purchase, the promise of payment, and the consummation of the sale of the illegal drug.

A buy-bust is usually carried out without warrant of arrest because the offender is expected to be caught in the act, in flagrante delicto.

But many of the families interviewed by the ABS-CBN team said that it was impossible for the police to conduct such operation because the victims were sleeping, eating, or simply hanging out in their homes right before they were killed.

Sick fought back

Such were the cases of Eduardo Remodaro, 66, and his son, Arcy, 42, who were killed while sleeping inside their ramshackle house in Morong Dulo, Tondo, Manila on July 8.

One of Eduardo’s relatives told an ABS-CBN news team that he and Arcy were together before the operation. Eduardo felt weak nursing his asthma and rheumatism, she said.

She said no buy-bust operation took place.

“Natutulog lang po sila. Napakatahimik dito noon,” she said.

Police’s version

The police report dated July 9 showed otherwise.

Members of the Manila Police District Station 7 reported they successfully bought a sachet of suspected shabu worth P1,000 before Eduardo and Arcy drew and fired their guns at the authorities.

A similar thing allegedly happened eight days later in Barangay Malanday, San Mateo, Rizal. Henrico Lauta alias Inlek, 47, was sleeping beside his live-in partner and son at around 1 a.m.when the police crashed into his home.

Eloisa Lauta, daughter of Herminio Lauta

Lauta’s eldest daughter Eloisa, 22, said she heard the police fire from inside the room “para magmukhang nanlaban [ang tatay ko.]”

A few seconds later, after Lauta’s wife and son were forced to leave the house, they heard another shot. By then, her father lay dead.

“Pinalabas po nila kasi, buy-bust operation,” Eloisa said. “Kumatok daw sila. Hindi po iyon totoo. Nandito po sya, nakahiga. Naka-brief pa nga po siya noon e.”

Policeman’s runner

Eloisa said her father was doing errands for a drug-pusher policeman in San Mateo. He had planned to surrender to the barangay the next Monday.

But that Saturday night, the police prevented him from doing so. She and the rest of the family believed that Lauta was killed because he knew a lot about drug dealings in the town.

Lauta died of a gunshot in his head, his death certificate showed.