Ressa, Santos on conviction: Judge 'failed to appreciate the role of the media' | ABS-CBN

ADVERTISEMENT

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

Ressa, Santos on conviction: Judge 'failed to appreciate the role of the media'

Ressa, Santos on conviction: Judge 'failed to appreciate the role of the media'

Mike Navallo,

ABS-CBN News

Published Jun 29, 2020 07:43 PM PHT

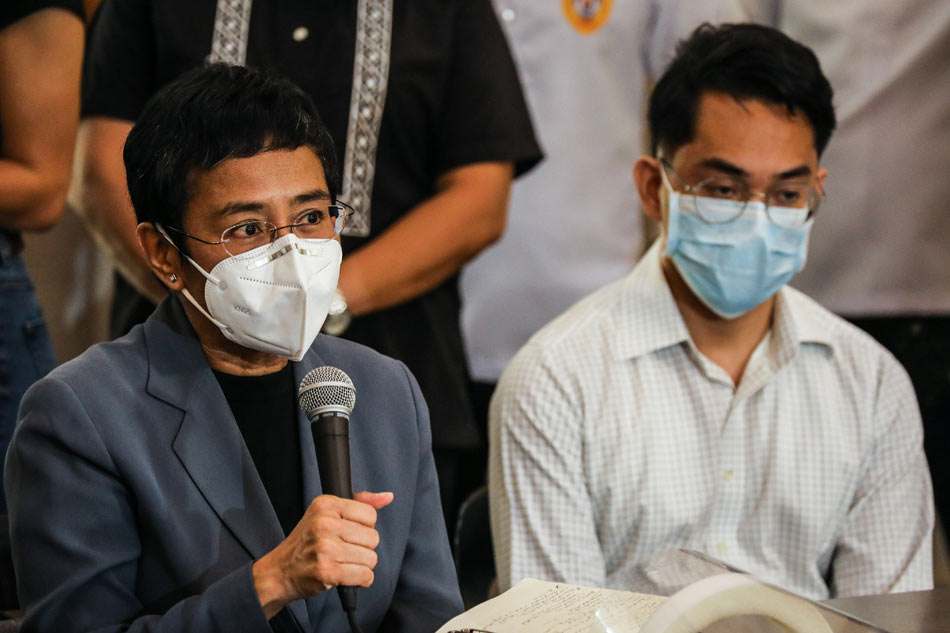

MANILA - Rappler CEO Maria Ressa and former Rappler writer-researcher Reynaldo Santos, Jr. on Monday asked a Manila court to reconsider its verdict convicting them of cyber libel over an article involving businessman Wilfredo Keng.

MANILA - Rappler CEO Maria Ressa and former Rappler writer-researcher Reynaldo Santos, Jr. on Monday asked a Manila court to reconsider its verdict convicting them of cyber libel over an article involving businessman Wilfredo Keng.

In a 132-page motion for reconsideration, Ressa and Santos urged Manila Regional Trial Court Branch 46 Judge Rainelda Estacio-Montesa to reframe her view of the case by recognizing "freedom of the press as a constitutional priority" and "not simply a narrow and parochial focus on a supposedly purely private interest."

In a 132-page motion for reconsideration, Ressa and Santos urged Manila Regional Trial Court Branch 46 Judge Rainelda Estacio-Montesa to reframe her view of the case by recognizing "freedom of the press as a constitutional priority" and "not simply a narrow and parochial focus on a supposedly purely private interest."

They accused her of failing to "appreciate the role of the media."

They accused her of failing to "appreciate the role of the media."

Montesa had sentenced Ressa and Santos to jail time ranging from 6 months and 1 day to 6 years, as well as to pay Keng P200,000 in moral damages and P200,000 in exemplary damages over a 2012 article that accused Keng of having a shady past and supposedly having links to some illegal activities.

Montesa had sentenced Ressa and Santos to jail time ranging from 6 months and 1 day to 6 years, as well as to pay Keng P200,000 in moral damages and P200,000 in exemplary damages over a 2012 article that accused Keng of having a shady past and supposedly having links to some illegal activities.

ADVERTISEMENT

RESSA, SANTOS: KENG IS A PUBLIC FIGURE

In finding Ressa and Santos guilty, Montesa ruled that because Keng is supposedly a private person, all defamatory statements against him are presumed to be malicious and the defense was not able to justify the publication of the defamatory statements.

In finding Ressa and Santos guilty, Montesa ruled that because Keng is supposedly a private person, all defamatory statements against him are presumed to be malicious and the defense was not able to justify the publication of the defamatory statements.

But for Ressa and Santos, Keng was not just a "private person."

But for Ressa and Santos, Keng was not just a "private person."

"It ought to have become clear to the court that the private complainant was not simply a 'private person' as not every 'private person' is assisted in the prosecution of his case by two prosecutors from the National Prosecution Service (NPS) and not by the regular trial prosecutor of the court," Ressa and Santos' lawyer, former Supreme Court spokesperson Theodore Te, argued.

"It ought to have become clear to the court that the private complainant was not simply a 'private person' as not every 'private person' is assisted in the prosecution of his case by two prosecutors from the National Prosecution Service (NPS) and not by the regular trial prosecutor of the court," Ressa and Santos' lawyer, former Supreme Court spokesperson Theodore Te, argued.

"It also ought to have become clear to the court that the subject of the allegedly offending article was not the private complainant but a then-sitting public official and certainly a public figure—the former Chief Justice," Te added.

"It also ought to have become clear to the court that the subject of the allegedly offending article was not the private complainant but a then-sitting public official and certainly a public figure—the former Chief Justice," Te added.

The Rappler article said that then Chief Justice Renato Corona, who was facing impeachment at the time, had been using luxury vehicles belonging to several personalities, including Keng.

The Rappler article said that then Chief Justice Renato Corona, who was facing impeachment at the time, had been using luxury vehicles belonging to several personalities, including Keng.

ADVERTISEMENT

The motion for reconsideration said Keng had in fact become a "public figure" because of his involvement in a public issue -- Corona's alleged penchant for using luxury vehicles of different personalities.

The motion for reconsideration said Keng had in fact become a "public figure" because of his involvement in a public issue -- Corona's alleged penchant for using luxury vehicles of different personalities.

It cited a 2005 case, Guingguing v. CA, where the Supreme Court ruled that "even non-government officials are considered public figures" and that to justify a conviction for criminal libel against a public figure, it must be shown that "the libelous statements were made or published with actual malice, meaning knowledge that the statement was false or with reckless disregard as to whether or not it was true."

It cited a 2005 case, Guingguing v. CA, where the Supreme Court ruled that "even non-government officials are considered public figures" and that to justify a conviction for criminal libel against a public figure, it must be shown that "the libelous statements were made or published with actual malice, meaning knowledge that the statement was false or with reckless disregard as to whether or not it was true."

The motion argued that Santos, in writing the article, did not act with malice as he collaborated with the late investigative reporter Aries Rufo and relied on an intelligence report and a news item published in a newspaper without adding commentary.

The motion argued that Santos, in writing the article, did not act with malice as he collaborated with the late investigative reporter Aries Rufo and relied on an intelligence report and a news item published in a newspaper without adding commentary.

The article, it said, is privileged and required proof of actual malice as it was "a fair and true report, made in good faith, without any comments or remarks, of any judicial, legislative, or other official proceedings which are not of confidential nature... or of any other act performed by public officers in the exercise of their functions."

The article, it said, is privileged and required proof of actual malice as it was "a fair and true report, made in good faith, without any comments or remarks, of any judicial, legislative, or other official proceedings which are not of confidential nature... or of any other act performed by public officers in the exercise of their functions."

PRESS FREEDOM

The motion added that because the matter was of public interest and because the cyber libel provision under the Cybercrime Prevention Act (RA 10175) clearly regulated content, the court should have applied the "strict scrutiny" test, which means that the prosecution needs to prove there was a "clear and present danger" to justify curtailment of speech.

The motion added that because the matter was of public interest and because the cyber libel provision under the Cybercrime Prevention Act (RA 10175) clearly regulated content, the court should have applied the "strict scrutiny" test, which means that the prosecution needs to prove there was a "clear and present danger" to justify curtailment of speech.

ADVERTISEMENT

"The court did not bother to scrutinize the law itself, contrary to the Supreme Court’s consistent command. Conclusively presumed to be aware of the 'preferred' status that freedom of the press enjoys in the constitutional hierarchy of rights, the court, with due respect, ought to have been more circumspect in applying what, on the face of the law, is clearly an offense that is content-based...," it said, noting the judge's "self-distancing" from the issue of press freedom.

"The court did not bother to scrutinize the law itself, contrary to the Supreme Court’s consistent command. Conclusively presumed to be aware of the 'preferred' status that freedom of the press enjoys in the constitutional hierarchy of rights, the court, with due respect, ought to have been more circumspect in applying what, on the face of the law, is clearly an offense that is content-based...," it said, noting the judge's "self-distancing" from the issue of press freedom.

Ressa took exception to Montesa's characterization of her "executive editor" title as supposedly a "clever ruse to avoid liability," calling it "unwarranted and absolutely unbecoming."

Ressa took exception to Montesa's characterization of her "executive editor" title as supposedly a "clever ruse to avoid liability," calling it "unwarranted and absolutely unbecoming."

"The court's role in the trial is to determine malice, not make malicious statements. Ascribing an underhanded and even unlawful motive--without assertion or proof--is malicious. It is utterly contemptuous and unbecoming of a judge," the motion said.

"The court's role in the trial is to determine malice, not make malicious statements. Ascribing an underhanded and even unlawful motive--without assertion or proof--is malicious. It is utterly contemptuous and unbecoming of a judge," the motion said.

It pointed out that Ressa's title had always been executive editor since Rappler launched in 2012, and it is a title used by The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Philippine Daily Inquirer.

It pointed out that Ressa's title had always been executive editor since Rappler launched in 2012, and it is a title used by The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Philippine Daily Inquirer.

"The court’s characterization of accused-movant’s title is not trivial. At best, it shows bias against accused-movant—how explain the interjection of a prejudicial characterization without the same having been asserted, let alone proved by the prosecution—at worst, it shows hostility and animosity. Whichever it is, that characterization is incompatible with due process and voids the judgment as it clearly shows that accused-movants were not accorded their due process rights," it said.

"The court’s characterization of accused-movant’s title is not trivial. At best, it shows bias against accused-movant—how explain the interjection of a prejudicial characterization without the same having been asserted, let alone proved by the prosecution—at worst, it shows hostility and animosity. Whichever it is, that characterization is incompatible with due process and voids the judgment as it clearly shows that accused-movants were not accorded their due process rights," it said.

ADVERTISEMENT

"In the process of arriving at its Decision, the court has resorted to language that borders on the sarcastic and, at times, crosses over to the partial."

"In the process of arriving at its Decision, the court has resorted to language that borders on the sarcastic and, at times, crosses over to the partial."

"It has also, with due respect, failed to appreciate the role of media, the importance of the guarantee of freedom of the press in the constitutional architecture, and the dire consequences of the Decision it has handed down going forward for those who would claim the protection of a free press and the right to freely hold and express an opinion as the only viable weapons in a war on truth and against truth tellers," it added.

"It has also, with due respect, failed to appreciate the role of media, the importance of the guarantee of freedom of the press in the constitutional architecture, and the dire consequences of the Decision it has handed down going forward for those who would claim the protection of a free press and the right to freely hold and express an opinion as the only viable weapons in a war on truth and against truth tellers," it added.

RESSA, SANTOS: CASE PRESCRIBED, ARTICLE NOT REPUBLISHED

Montesa, in her June 15 verdict, ruled that cyber libel prescribes in 12 years and that the February 2014 update of the article was a republication, making the Cybercrime Prevention Act applicable even if it was only enacted in September 2012, four months after the publication of the Keng article.

Montesa, in her June 15 verdict, ruled that cyber libel prescribes in 12 years and that the February 2014 update of the article was a republication, making the Cybercrime Prevention Act applicable even if it was only enacted in September 2012, four months after the publication of the Keng article.

Ressa and Santos insisted the court was wrong in applying the 12-year prescriptive period based on Act No. 3326, a 1926 law which gives an offended party 12 years within which to file a complaint if the penalty is punishable by jail time beyond 6 years.

Ressa and Santos insisted the court was wrong in applying the 12-year prescriptive period based on Act No. 3326, a 1926 law which gives an offended party 12 years within which to file a complaint if the penalty is punishable by jail time beyond 6 years.

They argued Act 3326 was not applicable to cyber libel because there is a specific prescriptive period of 1 year for libel under Art. 90 of the Revised Penal Code as amended by a 1966 law.

They argued Act 3326 was not applicable to cyber libel because there is a specific prescriptive period of 1 year for libel under Art. 90 of the Revised Penal Code as amended by a 1966 law.

ADVERTISEMENT

"Cyberlibel is not a new offense but simply a different means to commit an existing offense... As such, there was no need for the court to consider Act No. 3326," the motion said, citing a 2014 Supreme Court ruling in Disini vs. Secretary of Justice, the only case so far to deal with cyber libel.

"Cyberlibel is not a new offense but simply a different means to commit an existing offense... As such, there was no need for the court to consider Act No. 3326," the motion said, citing a 2014 Supreme Court ruling in Disini vs. Secretary of Justice, the only case so far to deal with cyber libel.

The motion also rejected Montesa's ruling that there was a republication.

The motion also rejected Montesa's ruling that there was a republication.

"With due respect, the court did not even bother to cite any shred of support for its unilateral statement that '(t)he (c)ourt considers the update a republication of the article,'" it said. "Of the 170 footnotes in the 36-page Decision, not a single reference is made to support this assertion."

"With due respect, the court did not even bother to cite any shred of support for its unilateral statement that '(t)he (c)ourt considers the update a republication of the article,'" it said. "Of the 170 footnotes in the 36-page Decision, not a single reference is made to support this assertion."

It added that the prosecution failed during the trial that an "update" is a "republication," as Montesa ruled, accusing her of "legislating several elements into the law."

It added that the prosecution failed during the trial that an "update" is a "republication," as Montesa ruled, accusing her of "legislating several elements into the law."

Ressa and Santos reiterated their position in their memorandum that there can only be "republication" if there was "substantial modification," not just a change in the spelling from "evaTion" to "evaSion."

Ressa and Santos reiterated their position in their memorandum that there can only be "republication" if there was "substantial modification," not just a change in the spelling from "evaTion" to "evaSion."

ADVERTISEMENT

The motion also said Santos had no role in the supposed republication while Ressa, for her part, was not involved in either the writing, publication and updating of the article.

In addition, both argued the Cybercrime Prevention Act did not take effect until April 22, 2014, when the TRO was lifted, after the supposed republication on February 19, 2014. The Constitution prohibits ex post facto or retroactive application of the law.

The motion also said Santos had no role in the supposed republication while Ressa, for her part, was not involved in either the writing, publication and updating of the article.

In addition, both argued the Cybercrime Prevention Act did not take effect until April 22, 2014, when the TRO was lifted, after the supposed republication on February 19, 2014. The Constitution prohibits ex post facto or retroactive application of the law.

OTHER MATTERS

Ressa and Santos also contested Montesa's ruling dismissing as "not binding, inadmissible, and hearsay" the testimonies of their witnesses -- National Bureau of Investigation Deputy Director Leo Edwin Leuterio and Rappler investigative head Chay Hofileña.

Ressa and Santos also contested Montesa's ruling dismissing as "not binding, inadmissible, and hearsay" the testimonies of their witnesses -- National Bureau of Investigation Deputy Director Leo Edwin Leuterio and Rappler investigative head Chay Hofileña.

Leuterio testified that the NBI Legal Service's recommendation was to dismiss the cyber libel case, while Hofileña said only a typographical error was changed in the 2012 article.

Leuterio testified that the NBI Legal Service's recommendation was to dismiss the cyber libel case, while Hofileña said only a typographical error was changed in the 2012 article.

The motion also objected to the judge faulting Ressa and Santos for not taking the witness stand. An accused should be convicted on the strength of the evidence presented by the prosecution and not on the weakness of his defense, it said.

The motion also objected to the judge faulting Ressa and Santos for not taking the witness stand. An accused should be convicted on the strength of the evidence presented by the prosecution and not on the weakness of his defense, it said.

The motion noted how, in contrast, Keng's testimony was the sole basis to prove damage to his reputation, while another witness presented by Keng was "not impartial.".

The motion noted how, in contrast, Keng's testimony was the sole basis to prove damage to his reputation, while another witness presented by Keng was "not impartial.".

ADVERTISEMENT

Keng's camp is expected to file their comment to the motion.

Keng's camp is expected to file their comment to the motion.

Montesa's ruling on the motion for reconsideration may be appealed to higher courts.

Montesa's ruling on the motion for reconsideration may be appealed to higher courts.

Read More:

Maria Ressa

Reynaldo Santos

Jr.

Judge Rainelda Estacio-Montesa

Manila RTC Br. 46

cyber libel

Wilfredo Keng

prescription

republication

Rappler

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT