Judge Manuel Real: Unsung American human rights hero | ABS-CBN

ADVERTISEMENT

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

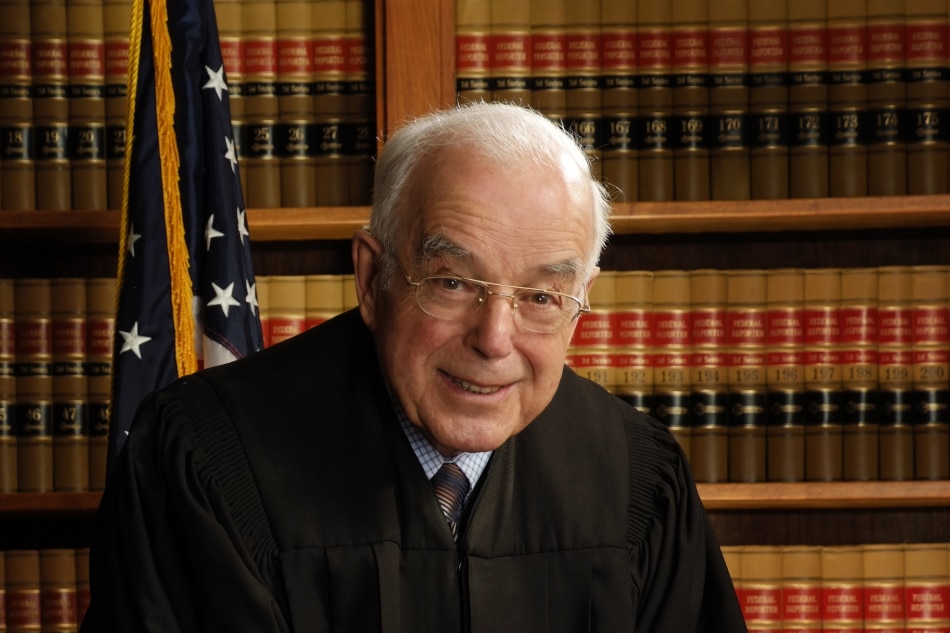

Judge Manuel Real: Unsung American human rights hero

Judge Manuel Real: Unsung American human rights hero

Gerry Lirio,

ABS-CBN News

Published Jun 02, 2020 02:21 AM PHT

“One's political belief is no ground for the State to torture him or to kill him.”

Judge Manuel Real, chief judge of the Los Angeles Federal Court, had this in mind like a mantra, but until after one morning in July 1989, when his superiors asked him to travel 2,000 miles away from California to Hawaii, he probably had no personal knowledge of human rights cases during martial law in the Philippines under President Ferdinand Marcos.

In an interview with ABS-CBN News, American lawyer Robert Swift remembered the Californian judge, the first to acknowledge judicially outside the Philippines through a court ruling the atrocities of the Marcos dictatorship by ordering the Marcos family to pay the martial law victims nearly US$2 billion in damages in January 1995.

Real died quietly in June last year while Swift was in Mindanao, south of the Philippine capital, distributing checks to indemnify some of the martial law victims, the fourth in a series of indemnification made possible because of Real’s rulings.

Swift remembered Real’s high regard for human lives, but until then, neither Real nor the Filipino victims had any idea that their lives would one day intertwine.

Fall of Marcos

“One's political belief is no ground for the State to torture him or to kill him.”

Judge Manuel Real, chief judge of the Los Angeles Federal Court, had this in mind like a mantra, but until after one morning in July 1989, when his superiors asked him to travel 2,000 miles away from California to Hawaii, he probably had no personal knowledge of human rights cases during martial law in the Philippines under President Ferdinand Marcos.

In an interview with ABS-CBN News, American lawyer Robert Swift remembered the Californian judge, the first to acknowledge judicially outside the Philippines through a court ruling the atrocities of the Marcos dictatorship by ordering the Marcos family to pay the martial law victims nearly US$2 billion in damages in January 1995.

Real died quietly in June last year while Swift was in Mindanao, south of the Philippine capital, distributing checks to indemnify some of the martial law victims, the fourth in a series of indemnification made possible because of Real’s rulings.

Swift remembered Real’s high regard for human lives, but until then, neither Real nor the Filipino victims had any idea that their lives would one day intertwine.

Fall of Marcos

Marcos, his wife, children and grandchildren and some 80 staff and supporters had landed in Hawaii after they were picked up from Malacanang by a US Air Force plane at the height of the military-backed, people power revolt in February 1986. They were frisked, fingerprinted, and interrogated, their suitcases full of voluminous cash and bank certificates, pieces of rare, high-end jewelry, weapons and many others all seized from a back-up plane, in what was probably the most humiliating experience for Marcos since he was tried and convicted of the September 1935 murder of Julio Nalundasan, his father’s political rival in their hometown in Ilocos Norte, north of Manila.

Marcos was served the complaints, each one a long and detailed accounts of disappearances, tortures, and executions of his critics and the looting of government coffers, two months into his exile in the paradise island.

Swift recalled the making of the complaints and how Judge Real became its central figure.

“A month into the post-EDSA euphoria, Manila was a city in transition from 20 years of virtual dictatorship,” Swift told ABS-CBN News, recalling the day he set foot on Philippines soil to meet his Filipino counterparts.

“Suddenly, there was freedom of the press. People no longer feared arrest and torture by the intelligence services. (The new president) Cory Aquino seemed to walk on water.”

Swift flew to Manila and met with Filipino lawyers Jose Mari Velez, Romeo Capulong, Rene Saguisag, and later Rod Domingo, among others. They agreed to gather the martial law victims across the country, through Selda, an organization of ex-political detainees led by activist Marie Hilao, up until they numbered 9,539, and filed the lawsuit. Hilao’s older sister, Liliosa, a student activist in 1973 was widely believed as the first murder case under martial law. Hilao gathered the victims for their affidavits.

First judge, a defeat

Marcos, his wife, children and grandchildren and some 80 staff and supporters had landed in Hawaii after they were picked up from Malacanang by a US Air Force plane at the height of the military-backed, people power revolt in February 1986. They were frisked, fingerprinted, and interrogated, their suitcases full of voluminous cash and bank certificates, pieces of rare, high-end jewelry, weapons and many others all seized from a back-up plane, in what was probably the most humiliating experience for Marcos since he was tried and convicted of the September 1935 murder of Julio Nalundasan, his father’s political rival in their hometown in Ilocos Norte, north of Manila.

Marcos was served the complaints, each one a long and detailed accounts of disappearances, tortures, and executions of his critics and the looting of government coffers, two months into his exile in the paradise island.

Swift recalled the making of the complaints and how Judge Real became its central figure.

“A month into the post-EDSA euphoria, Manila was a city in transition from 20 years of virtual dictatorship,” Swift told ABS-CBN News, recalling the day he set foot on Philippines soil to meet his Filipino counterparts.

“Suddenly, there was freedom of the press. People no longer feared arrest and torture by the intelligence services. (The new president) Cory Aquino seemed to walk on water.”

Swift flew to Manila and met with Filipino lawyers Jose Mari Velez, Romeo Capulong, Rene Saguisag, and later Rod Domingo, among others. They agreed to gather the martial law victims across the country, through Selda, an organization of ex-political detainees led by activist Marie Hilao, up until they numbered 9,539, and filed the lawsuit. Hilao’s older sister, Liliosa, a student activist in 1973 was widely believed as the first murder case under martial law. Hilao gathered the victims for their affidavits.

First judge, a defeat

Real was to take the case from a colleague, Chief Judge Harold Fong of Honolulu, who had dismissed the complaints at Marcos’ plea based on State doctrine restricting an American court to rule on matters involving a foreign country, saying the “Act of State” doctrine rendered the case non-justiciable.

“During oral argument,” Swift recounted, “it was clear that Judge Fong was antagonistic to the case and dismissed it.”

But Swift, the Filipino lawyers, and the thousands of human rights victims and their families refused to lose the case, despite legal technicalities and budget constraints.

“(We) filed the case in Hawaii federal court in April 1986,” Swift said, “alleging that Marcos had orchestrated and directed torture, summary execution and disappearance against thousands of Filipinos.

A higher court reversed Fong’s dismissal on appeal, paving for Real’s entry in July 1989.

Then 61-years old, Judge Real went to Hawaii to preside over the complaints against Marcos for the crimes his family supposedly committed during his 20-year rule, mostly during the 14 years when he placed the entire Philippines under martial law.

He was seven years younger than Marcos, the most celebrated bar topnotcher in the Philippines and a close ally of the Reagan administration.

A law called Alien Tort

Real was to take the case from a colleague, Chief Judge Harold Fong of Honolulu, who had dismissed the complaints at Marcos’ plea based on State doctrine restricting an American court to rule on matters involving a foreign country, saying the “Act of State” doctrine rendered the case non-justiciable.

“During oral argument,” Swift recounted, “it was clear that Judge Fong was antagonistic to the case and dismissed it.”

But Swift, the Filipino lawyers, and the thousands of human rights victims and their families refused to lose the case, despite legal technicalities and budget constraints.

“(We) filed the case in Hawaii federal court in April 1986,” Swift said, “alleging that Marcos had orchestrated and directed torture, summary execution and disappearance against thousands of Filipinos.

A higher court reversed Fong’s dismissal on appeal, paving for Real’s entry in July 1989.

Then 61-years old, Judge Real went to Hawaii to preside over the complaints against Marcos for the crimes his family supposedly committed during his 20-year rule, mostly during the 14 years when he placed the entire Philippines under martial law.

He was seven years younger than Marcos, the most celebrated bar topnotcher in the Philippines and a close ally of the Reagan administration.

A law called Alien Tort

The Filipinos liked the idea of suing Marcos in the US, Swift said, but they had mixed feelings about getting a favorable verdict.

Swift had never met Judge Real until late in 1990 when Swift showed up in the judge’s sala to represent the victims. He remembered his first impression of his more senior fellow American lawyer.

“One of Judge Real’s strengths as a judge was his encyclopedic knowledge of the Rules of Evidence,” he said. “He listened carefully to each question posed by an attorney. Often, he struck a question even before opposing counsel could voice an objection.”

Swift would later unearth an esoteric American law, the Alien Tort Statute, also called the Alien Tort Claims Act, which reads: "The district courts shall have original jurisdiction of any civil action by an alien for a tort only, committed in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States."

According to a legal dictionary, tort refers to a wrongful act for which relief may be obtained in the form of damages.

First enacted in 1790, the Tort law gave US federal courts jurisdiction over cases brought by foreigners alleging violations of international law. Since 1980, courts have interpreted this statute to allow foreign citizens to seek remedies in American courts for human rights violations even outside the United States.

Not a reason to kill

The Filipinos liked the idea of suing Marcos in the US, Swift said, but they had mixed feelings about getting a favorable verdict.

Swift had never met Judge Real until late in 1990 when Swift showed up in the judge’s sala to represent the victims. He remembered his first impression of his more senior fellow American lawyer.

“One of Judge Real’s strengths as a judge was his encyclopedic knowledge of the Rules of Evidence,” he said. “He listened carefully to each question posed by an attorney. Often, he struck a question even before opposing counsel could voice an objection.”

Swift would later unearth an esoteric American law, the Alien Tort Statute, also called the Alien Tort Claims Act, which reads: "The district courts shall have original jurisdiction of any civil action by an alien for a tort only, committed in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States."

According to a legal dictionary, tort refers to a wrongful act for which relief may be obtained in the form of damages.

First enacted in 1790, the Tort law gave US federal courts jurisdiction over cases brought by foreigners alleging violations of international law. Since 1980, courts have interpreted this statute to allow foreign citizens to seek remedies in American courts for human rights violations even outside the United States.

Not a reason to kill

ADVERTISEMENT

Before the trial began, Swift said, Judge Real made it known that the Marcoses would not be allowed to introduce evidence that would assert that the complainants were either communists or communist sympathizers.

“The logic was simple: political beliefs and practices are not a defense to torture, summary execution or disappearance,” he said, quoting the judge.

“During the trial, the Marcos attorneys tried to question witnesses about communism. Each time, the judge struck the question and advised the jury to disregard it.”

It surprised even the prosecutors. With Judge Real at the helm, the victims saw some hope. By then, Real had been on the bench 25 years and had carved a reputation as a no-nonsense judge.

Real’s credentials

Before the trial began, Swift said, Judge Real made it known that the Marcoses would not be allowed to introduce evidence that would assert that the complainants were either communists or communist sympathizers.

“The logic was simple: political beliefs and practices are not a defense to torture, summary execution or disappearance,” he said, quoting the judge.

“During the trial, the Marcos attorneys tried to question witnesses about communism. Each time, the judge struck the question and advised the jury to disregard it.”

It surprised even the prosecutors. With Judge Real at the helm, the victims saw some hope. By then, Real had been on the bench 25 years and had carved a reputation as a no-nonsense judge.

Real’s credentials

Born in 1924 in San Pedro, California, near Long Beach, Judge Real got his Bachelor of Science in 1944 from the University of Southern California and his Bachelor of Laws (LLB) from Loyola Law School in 1951, according to the website of the United States District Court for the Central District of California. He was one of the first district judges appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson to the Central District of California in 1966.

Judge Real was also the Central District’s longest serving chief judge, holding court from 1982 to 1993, according to the website. One of the nation’s first Hispanic federal judges, he was active for many years in international rule-of-law programs, lecturing in Spanish in Argentina, Chile and Uruguay on comparative legal systems.

Inside the courtroom, Swift remembered Real telling lawyers to strictly follow the court rules. He would sanction lawyers who failed to do so. He read motions carefully and was lively during oral argument, he said.

“If he disagreed with your position, he was quick to tell you that,” he said. “But when the judge held a conference of attorneys in his chamber, he shook everyone’s hand, had a big, engaging smile, hearty laugh and was very affable.”

Marcoses get new lawyers

Born in 1924 in San Pedro, California, near Long Beach, Judge Real got his Bachelor of Science in 1944 from the University of Southern California and his Bachelor of Laws (LLB) from Loyola Law School in 1951, according to the website of the United States District Court for the Central District of California. He was one of the first district judges appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson to the Central District of California in 1966.

Judge Real was also the Central District’s longest serving chief judge, holding court from 1982 to 1993, according to the website. One of the nation’s first Hispanic federal judges, he was active for many years in international rule-of-law programs, lecturing in Spanish in Argentina, Chile and Uruguay on comparative legal systems.

Inside the courtroom, Swift remembered Real telling lawyers to strictly follow the court rules. He would sanction lawyers who failed to do so. He read motions carefully and was lively during oral argument, he said.

“If he disagreed with your position, he was quick to tell you that,” he said. “But when the judge held a conference of attorneys in his chamber, he shook everyone’s hand, had a big, engaging smile, hearty laugh and was very affable.”

Marcoses get new lawyers

With Real’s takeover, the Marcoses hired different lawyers: James Linn to represent former First Lady Imelda and the estate; and John Bartko to represent son Ferdinand Jr. and the estate.

Linn was a legendary Oklahoma lawyer who defended and got an acquittal for rock star David Bowie on sexual charges. He died in October 2006 at age 83. Bartko is one of the top-rated business litigation lawyers in San Francisco, California.

“They were Imelda’s counsel in the criminal case in New York, which ended in her acquittal,” Swift said. “They were paid about $10 million,” he added.

Marcos died in September 1989, leaving his wife Imelda and son as substituted defendants.

And the first thing Linn and Bartko did was to file a new motion asking Real to dismiss the case.

Before showing up at the hearing, Real read the motion and the counter arguments, and had tough questions for both sides, he added. In the end, Judge Real dismissed the motion.

First Class Suit ever

With Real’s takeover, the Marcoses hired different lawyers: James Linn to represent former First Lady Imelda and the estate; and John Bartko to represent son Ferdinand Jr. and the estate.

Linn was a legendary Oklahoma lawyer who defended and got an acquittal for rock star David Bowie on sexual charges. He died in October 2006 at age 83. Bartko is one of the top-rated business litigation lawyers in San Francisco, California.

“They were Imelda’s counsel in the criminal case in New York, which ended in her acquittal,” Swift said. “They were paid about $10 million,” he added.

Marcos died in September 1989, leaving his wife Imelda and son as substituted defendants.

And the first thing Linn and Bartko did was to file a new motion asking Real to dismiss the case.

Before showing up at the hearing, Real read the motion and the counter arguments, and had tough questions for both sides, he added. In the end, Judge Real dismissed the motion.

First Class Suit ever

“Judge Real was not prone to writing opinions,” Swift said. “And he did not write an opinion. By denying the motion, the stage was set for two things: class certification and discovery.”

In 1991, Real declared the case a Class Suit, as Swift envisioned, and the trial of the case against the Marcoses, docketed as MDL 840 (Multi District Litigation), was set in the Federal District Court of Hawaii. It was a consolidation of all human rights cases filed against Marcos.

It was the first human rights class action filed in the United States, or anywhere in the world. The filing was as historic as it was unprecedented trying a case for serious human rights abuses against a former head of state, except possibly the Nurenburg War Crimes Trial of 1946 where 11 nations tried Nazis for crimes of international law committed during World War II.

Thus, there was no direct precedent for Judge Real either in granting or denying class certification.

Class of abused Filipinos

“Judge Real was not prone to writing opinions,” Swift said. “And he did not write an opinion. By denying the motion, the stage was set for two things: class certification and discovery.”

In 1991, Real declared the case a Class Suit, as Swift envisioned, and the trial of the case against the Marcoses, docketed as MDL 840 (Multi District Litigation), was set in the Federal District Court of Hawaii. It was a consolidation of all human rights cases filed against Marcos.

It was the first human rights class action filed in the United States, or anywhere in the world. The filing was as historic as it was unprecedented trying a case for serious human rights abuses against a former head of state, except possibly the Nurenburg War Crimes Trial of 1946 where 11 nations tried Nazis for crimes of international law committed during World War II.

Thus, there was no direct precedent for Judge Real either in granting or denying class certification.

Class of abused Filipinos

Real certified the case as a class action, defining class as all civilian citizens of the Philippines who were tortured, summarily executed by Philippine military or paramilitary groups between 1972 and 1986, including the survivors of the deceased complainants and the desaparecidos, referring to those the government agents had secretly arrested and murdered.

“A class can be certified on several grounds,” said Swift, “most often where there are common issues as to damages.”

The court was dealt the case in three parts: addressing liability, exemplary damages, and compensatory damages. In this case, the damages were different for each class member, each having different level of abuse.

“So I contended that it could be certified as a limited fund case since: One, Imelda had stated in an interrogatory answer that the Marcos estate had just $300 million in assets, including their Swiss bank accounts, and Two: total damages for the class would exceed $300 million,” Swift said.

“The problem which confronted me was how to prove, at this stage of the case, that damages for the class would exceed $300 million. I decided to combine the class certification hearing with a hearing on damages in a related case,” he said.

Real’s resolve

Real certified the case as a class action, defining class as all civilian citizens of the Philippines who were tortured, summarily executed by Philippine military or paramilitary groups between 1972 and 1986, including the survivors of the deceased complainants and the desaparecidos, referring to those the government agents had secretly arrested and murdered.

“A class can be certified on several grounds,” said Swift, “most often where there are common issues as to damages.”

The court was dealt the case in three parts: addressing liability, exemplary damages, and compensatory damages. In this case, the damages were different for each class member, each having different level of abuse.

“So I contended that it could be certified as a limited fund case since: One, Imelda had stated in an interrogatory answer that the Marcos estate had just $300 million in assets, including their Swiss bank accounts, and Two: total damages for the class would exceed $300 million,” Swift said.

“The problem which confronted me was how to prove, at this stage of the case, that damages for the class would exceed $300 million. I decided to combine the class certification hearing with a hearing on damages in a related case,” he said.

Real’s resolve

ADVERTISEMENT

That related case was the lawsuit of Trajano vs. Imee Marcos, a case of torture and murder of college student Archimedes Trajano who questioned Marcos’ daughter Imee about the family wealth after she delivered a speech at a university in the Philippines in August 1977.

Real took cognizance of the Trajano case. To develop evidence for damages, Real allowed the remains of Trajano dug up and sent to Hawaii where they were examined by a forensic pathologist. The pathologist brought the remains during the hearing and displayed them, including Trajano’s cracked skull.

Looking directly at Judge Real, the pathologist explained how violent blows shattered Trajano’s skull.

“As the blackened skull was lifted by the pathologist from a Tupperware container,” Swift recalled, “there was an audible wailing from Trajano’s mother and relatives in the courtroom.”

Shocked, Real subsequently ordered a recess. When he returned, the judge ordered Imee to pay the Trajanos more than $4 million in compensatory and punitive damages. But Imee managed to fly to Morocco and evade the hearing on damages. She never paid any part of the judgment, and Mrs. Trajano, the mother of the victim, died in poverty a few years later.

That related case was the lawsuit of Trajano vs. Imee Marcos, a case of torture and murder of college student Archimedes Trajano who questioned Marcos’ daughter Imee about the family wealth after she delivered a speech at a university in the Philippines in August 1977.

Real took cognizance of the Trajano case. To develop evidence for damages, Real allowed the remains of Trajano dug up and sent to Hawaii where they were examined by a forensic pathologist. The pathologist brought the remains during the hearing and displayed them, including Trajano’s cracked skull.

Looking directly at Judge Real, the pathologist explained how violent blows shattered Trajano’s skull.

“As the blackened skull was lifted by the pathologist from a Tupperware container,” Swift recalled, “there was an audible wailing from Trajano’s mother and relatives in the courtroom.”

Shocked, Real subsequently ordered a recess. When he returned, the judge ordered Imee to pay the Trajanos more than $4 million in compensatory and punitive damages. But Imee managed to fly to Morocco and evade the hearing on damages. She never paid any part of the judgment, and Mrs. Trajano, the mother of the victim, died in poverty a few years later.

But that preceded the class certification hearing of the Class Suit.

9-year litigation begins

But that preceded the class certification hearing of the Class Suit.

9-year litigation begins

Judge Real thus ordered the case against the Marcoses a certified Class Suit, finding that it was a “limited fund” case based on what Imelda stated were the assets of the Marcos estate. He said that Swift had proven that damages for the class would likely exceed $300 million based on the damages awarded in the Trajano case and the likely size of the class. He asked Swift to send notices to all class members.

That began an expensive and exhausting, long-distance, roller-coaster trial of the Marcoses, and an uphill litigation for the martial law victims, some of whom had to relive their nightmare, like being tortured all over again to prove every element of the heinous abuses committed against them. The men had to recall how their balls were electrocuted. The women had to recount how some of them were raped, and how some of their sons and daughters, brothers and friends were murdered, or disappeared without a trace, if only to qualify as a rightful claimant to the Marcos estate.

Holding a trial in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, according to Swift, was a logistical challenge since every witness had to be flown to Hawaii and provided with a hotel room. The litigation lasted for nine years.

Rules of Real

Judge Real thus ordered the case against the Marcoses a certified Class Suit, finding that it was a “limited fund” case based on what Imelda stated were the assets of the Marcos estate. He said that Swift had proven that damages for the class would likely exceed $300 million based on the damages awarded in the Trajano case and the likely size of the class. He asked Swift to send notices to all class members.

That began an expensive and exhausting, long-distance, roller-coaster trial of the Marcoses, and an uphill litigation for the martial law victims, some of whom had to relive their nightmare, like being tortured all over again to prove every element of the heinous abuses committed against them. The men had to recall how their balls were electrocuted. The women had to recount how some of them were raped, and how some of their sons and daughters, brothers and friends were murdered, or disappeared without a trace, if only to qualify as a rightful claimant to the Marcos estate.

Holding a trial in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, according to Swift, was a logistical challenge since every witness had to be flown to Hawaii and provided with a hotel room. The litigation lasted for nine years.

Rules of Real

Judge Real imposed other rules. Because Marcos was known in Hawaii, having been in the paradise for official visits all met with welcome cheers and speeches, Real sent out summons to 500 Hawaiians from five islands who had to respond to five questions as to their pre-existing knowledge or prejudices of the Marcoses and the Philippines.

From 500, he chose 65 potential jurors, otherwise called the Grand Venire, assembled in the courtroom for selection.

Judge Real required that opening arguments be made to the grand venire of 65 before jury selection began. His thinking was that potential jurors needed more information about the case before he could say whether they were biased or prejudiced.

In the end, from the pool of 65, Real settled with eight jurors.

Judge Real also required that the direct testimony of all expert witnesses had to be in writing and submitted several weeks before trial started.

“This meant that direct testimony would be read to the jury by the expert witness followed by vigorous cross examination,” Swift said.

“There would be no opportunity for an expert witness to supplement his direct testimony from the witness stand,” he added.

Real first scheduled a jury trial in September 1992. Swift presented eight expert witnesses, among them, Fr. Joaquin Bernas who testified about how Marcos subverted the 1973 Philippine Constitution; and Sister Mariani Dimaranan, who testified about the documentation of human rights abuses by Task Force Detainees, a human rights group she led in the Philippines.

Courtroom hours

Judge Real imposed other rules. Because Marcos was known in Hawaii, having been in the paradise for official visits all met with welcome cheers and speeches, Real sent out summons to 500 Hawaiians from five islands who had to respond to five questions as to their pre-existing knowledge or prejudices of the Marcoses and the Philippines.

From 500, he chose 65 potential jurors, otherwise called the Grand Venire, assembled in the courtroom for selection.

Judge Real required that opening arguments be made to the grand venire of 65 before jury selection began. His thinking was that potential jurors needed more information about the case before he could say whether they were biased or prejudiced.

In the end, from the pool of 65, Real settled with eight jurors.

Judge Real also required that the direct testimony of all expert witnesses had to be in writing and submitted several weeks before trial started.

“This meant that direct testimony would be read to the jury by the expert witness followed by vigorous cross examination,” Swift said.

“There would be no opportunity for an expert witness to supplement his direct testimony from the witness stand,” he added.

Real first scheduled a jury trial in September 1992. Swift presented eight expert witnesses, among them, Fr. Joaquin Bernas who testified about how Marcos subverted the 1973 Philippine Constitution; and Sister Mariani Dimaranan, who testified about the documentation of human rights abuses by Task Force Detainees, a human rights group she led in the Philippines.

Courtroom hours

Real had imposed one more condition.

Real had imposed one more condition.

ADVERTISEMENT

“He limited the number of courtroom hours that each side could present its evidence. Each side had 30 hours. At the end of each day of the trial, the judge’s law clerk told us how many hours and minutes each side had left,” Swift said.

“Beyond this, the judge limited closing argument to 30 minutes for each side. To summarize the evidence in a four-week trial in 30 minutes seemed like an impossibility,” he added.

Before case was sent to the jury, Judge Real had “to charge”--a legal term meant to instruct--the jury as to the law that would apply during the trial. The lawyers of both sides submitted proposed jury charges to the judge, and he then decided the wording of jury charges.

Reading all the jury charges took 30 minutes or more. The correctness of jury charges was usually a central issue on appeal.

In the history of the US courts, Swift said, there had never been a trial alleging violations of international law involving torture, summary execution and disappearance, so Judge Real was in uncharted territory.

A key charge given by Judge Real to the jury was: “To determine if the estate of the late President Marcos is liable to any plaintiff for wrong alleged by the plaintiffs, you must determine whether the injury alleged by a plaintiff has been shown by a preponderance of the evidence to have been caused by reason of a person being taken into custody by an order of Ferdinand Marcos or under his authority.”

In fact, the Marcoses appealed this jury charge to a higher court alleging that it was inadequate to establish liability.

The 9th Circuit affirmed the jury charge, stating that “the challenged instruction came directly after the district court's main instruction on liability, which required the jury to find either that Marcos had directed, ordered, conspired with, or aided in torture, summary execution, and disappearance, or that he had knowledge of that conduct and failed to use his power to prevent it,” Swift said.

“Thus, it is clear that the jury was required to find not merely that the (complainants) were taken into custody under Marcos' authority but that once in custody (they) were tortured, executed, or disappeared on Marcos' orders or with his knowledge,” he added.

Finally, the verdict

“He limited the number of courtroom hours that each side could present its evidence. Each side had 30 hours. At the end of each day of the trial, the judge’s law clerk told us how many hours and minutes each side had left,” Swift said.

“Beyond this, the judge limited closing argument to 30 minutes for each side. To summarize the evidence in a four-week trial in 30 minutes seemed like an impossibility,” he added.

Before case was sent to the jury, Judge Real had “to charge”--a legal term meant to instruct--the jury as to the law that would apply during the trial. The lawyers of both sides submitted proposed jury charges to the judge, and he then decided the wording of jury charges.

Reading all the jury charges took 30 minutes or more. The correctness of jury charges was usually a central issue on appeal.

In the history of the US courts, Swift said, there had never been a trial alleging violations of international law involving torture, summary execution and disappearance, so Judge Real was in uncharted territory.

A key charge given by Judge Real to the jury was: “To determine if the estate of the late President Marcos is liable to any plaintiff for wrong alleged by the plaintiffs, you must determine whether the injury alleged by a plaintiff has been shown by a preponderance of the evidence to have been caused by reason of a person being taken into custody by an order of Ferdinand Marcos or under his authority.”

In fact, the Marcoses appealed this jury charge to a higher court alleging that it was inadequate to establish liability.

The 9th Circuit affirmed the jury charge, stating that “the challenged instruction came directly after the district court's main instruction on liability, which required the jury to find either that Marcos had directed, ordered, conspired with, or aided in torture, summary execution, and disappearance, or that he had knowledge of that conduct and failed to use his power to prevent it,” Swift said.

“Thus, it is clear that the jury was required to find not merely that the (complainants) were taken into custody under Marcos' authority but that once in custody (they) were tortured, executed, or disappeared on Marcos' orders or with his knowledge,” he added.

Finally, the verdict

The jury deliberated for several days. When it handed the verdict, the courtroom was full and the tension was palpable.

Judge Real showed no emotion and instructed the reading of the verdict aloud. The jury found that the estate of Ferdinand Marcos was liable to the complainants. He thanked the jury for its service and said that it would be notified when the trial for damages would start. He quietly left the bench.

In November 1995, Judge Real came out with the jury verdict awarding $1.964 billion to 9,539 human rights victims. The judgment was affirmed on appeal.

Although the Marcoses have never voluntarily paid any money to the class, the victims nonetheless indirectly recovered about $37 million from Marcos assets, including from recovered Imelda’s collection of high-end paintings.

18 years later in Manila

The jury deliberated for several days. When it handed the verdict, the courtroom was full and the tension was palpable.

Judge Real showed no emotion and instructed the reading of the verdict aloud. The jury found that the estate of Ferdinand Marcos was liable to the complainants. He thanked the jury for its service and said that it would be notified when the trial for damages would start. He quietly left the bench.

In November 1995, Judge Real came out with the jury verdict awarding $1.964 billion to 9,539 human rights victims. The judgment was affirmed on appeal.

Although the Marcoses have never voluntarily paid any money to the class, the victims nonetheless indirectly recovered about $37 million from Marcos assets, including from recovered Imelda’s collection of high-end paintings.

18 years later in Manila

In February 2013, President Benigno Simeon Aquino III signed into law creating a P10-billion indemnification package for the martial law victims.

In February 2013, President Benigno Simeon Aquino III signed into law creating a P10-billion indemnification package for the martial law victims.

As against Real’s original $2-billion judgment, Swift said the P10-billion compensation package is inadequate to give justice to the victims, except that the Philippine law made a public and symbolic acknowledgment of the atrocities during the Marcos regime, though the acknowledgment came 18 years late.

Swift said he was thankful that it was Judge Real who handled the Hawaii case. “As a jurist, (Real) was a consummate professional and allowed each side an equal opportunity to present its case to the jury,” he said.

Although most of his work was complete after judgment was entered in 1995, Real maintained jurisdiction over proceedings to collect damages in the next 25 years. He authorized Swift to run after Imelda’s paintings, sell them, and distribute the proceeds to the complainants.

“I was able to collect money from the Marcoses and distribute it to the class members,” Swift said. “Judge Real was very pleased.” The last distribution was between May and July last year, and it was the fourth time.

As against Real’s original $2-billion judgment, Swift said the P10-billion compensation package is inadequate to give justice to the victims, except that the Philippine law made a public and symbolic acknowledgment of the atrocities during the Marcos regime, though the acknowledgment came 18 years late.

Swift said he was thankful that it was Judge Real who handled the Hawaii case. “As a jurist, (Real) was a consummate professional and allowed each side an equal opportunity to present its case to the jury,” he said.

Although most of his work was complete after judgment was entered in 1995, Real maintained jurisdiction over proceedings to collect damages in the next 25 years. He authorized Swift to run after Imelda’s paintings, sell them, and distribute the proceeds to the complainants.

“I was able to collect money from the Marcoses and distribute it to the class members,” Swift said. “Judge Real was very pleased.” The last distribution was between May and July last year, and it was the fourth time.

Judge Real had outlived about 100 martial law victims, some of whom died of various ailments, including violent persecution in the post-Marcos era. Some victims who are still alive are now in the twilight of their years, suffering geriatric issues, ranging from diabetes to hypertension, and are still nursing the wounds inflicted by the years of living dangerously.

Judge Real had outlived about 100 martial law victims, some of whom died of various ailments, including violent persecution in the post-Marcos era. Some victims who are still alive are now in the twilight of their years, suffering geriatric issues, ranging from diabetes to hypertension, and are still nursing the wounds inflicted by the years of living dangerously.

ADVERTISEMENT

Real outlived other people who helped the Marcos victims in the long trial, among them Velez who died in 1991, Capulong in 2012, and Dimaranan in 2005.

Real outlived other people who helped the Marcos victims in the long trial, among them Velez who died in 1991, Capulong in 2012, and Dimaranan in 2005.

Swift last saw Judge Real on March 28, 2019 following a hearing on a motion to approve a settlement and distribution of the proceeds in the sale of three Imelda paintings --“L’Eglise a La Seine a Vetheuil” by French impressionist Claude Monet; “Langland Bay” by British landscape artist Alfred Sisley; and “Le Cypres de Djenan Sidi Said”, also known as “Algerian View” by French painter Albert Marquet.

Swift last saw Judge Real on March 28, 2019 following a hearing on a motion to approve a settlement and distribution of the proceeds in the sale of three Imelda paintings --“L’Eglise a La Seine a Vetheuil” by French impressionist Claude Monet; “Langland Bay” by British landscape artist Alfred Sisley; and “Le Cypres de Djenan Sidi Said”, also known as “Algerian View” by French painter Albert Marquet.

That hearing paved the way for the fourth distribution that began in May last year.

That hearing paved the way for the fourth distribution that began in May last year.

Real: Regards to HR fighters

“Judge Real is old, slightly hard of hearing, personable and nattily dressed. We reminisced about some aspects of the case,” Swift told this newsman last year.

“Judge Real is old, slightly hard of hearing, personable and nattily dressed. We reminisced about some aspects of the case,” Swift told this newsman last year.

“I have no doubt that Judge Real regarded the Class Suit as one of the high points in his more than 50 years on the federal bench.”

Real died almost unnoticed in the Philippines on June 26, 2019, five months after he celebrated his 95th birthday. His death reminded us of what the late actor Kirk Douglas said when he stood by American screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, whose life story was turned into a movie in memory of “Hollywood 10,” a blacklisted group of suspected communists and communist sympathizers, at the height of communist witch-hunt in the US:

“I have no doubt that Judge Real regarded the Class Suit as one of the high points in his more than 50 years on the federal bench.”

Real died almost unnoticed in the Philippines on June 26, 2019, five months after he celebrated his 95th birthday. His death reminded us of what the late actor Kirk Douglas said when he stood by American screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, whose life story was turned into a movie in memory of “Hollywood 10,” a blacklisted group of suspected communists and communist sympathizers, at the height of communist witch-hunt in the US:

ADVERTISEMENT

“There are times when one has to stand up for his principle. I am so proud of my fellow actors who use their public influence to speak out against injustice. At 98 years old, I have learned one lesson from history: It very often repeats itself. I hope that Trumbo, a fine film, will remind all of us that the Blacklist was a terrible time in our country, but that we must learn from it so that it will never happen again.”

“There are times when one has to stand up for his principle. I am so proud of my fellow actors who use their public influence to speak out against injustice. At 98 years old, I have learned one lesson from history: It very often repeats itself. I hope that Trumbo, a fine film, will remind all of us that the Blacklist was a terrible time in our country, but that we must learn from it so that it will never happen again.”

Read More:

California judges

Tort law

Alien Tort Claims Act

human rights

Ferdinand Marcos

Judge Manuel Real

Hispanic lawyers

Marcos dictatorship

desaparecidos

Robert Swift

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT