How punk rock and photography saved a Filipino club in LA | ABS-CBN

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

How punk rock and photography saved a Filipino club in LA

How punk rock and photography saved a Filipino club in LA

Paolo Vergara,

ANC-X

Published May 29, 2018 07:03 PM PHT

|

Updated May 29, 2018 07:13 PM PHT

The year was 1976 and the Mabuhay Gardens had seen better days. The Bay Area joint was a restaurant and club that hosted big-timers like Amapola Cabase, Whoopi Goldberg, and Robin Williams. Arriving in San Francisco to look for opportunities, music promoter Dirk Dirksen was introduced to Mabuhay’s proprietor, the late Ness Aquino.

The year was 1976 and the Mabuhay Gardens had seen better days. The Bay Area joint was a restaurant and club that hosted big-timers like Amapola Cabase, Whoopi Goldberg, and Robin Williams. Arriving in San Francisco to look for opportunities, music promoter Dirk Dirksen was introduced to Mabuhay’s proprietor, the late Ness Aquino.

A known conservative, it’s a wonder that Aquino allowed the punk scene into his halls. Not much is said about him in punk zines today, save that the movement owes much to him for his patronage and for providing a space for obscure bands (back in the day, the list included the Dead Kennedys, The Nuns, and The Avengers).

A known conservative, it’s a wonder that Aquino allowed the punk scene into his halls. Not much is said about him in punk zines today, save that the movement owes much to him for his patronage and for providing a space for obscure bands (back in the day, the list included the Dead Kennedys, The Nuns, and The Avengers).

Another habitué and hallowed guest of Mabuhay Gardens was American artist Bruce Conner. Conner was one of the few artists who kept things edgy and uncomfortable—he was the consummate artist’s artist. John Lennon, devoted to Conner’s work, famously sent him fan letters.

Another habitué and hallowed guest of Mabuhay Gardens was American artist Bruce Conner. Conner was one of the few artists who kept things edgy and uncomfortable—he was the consummate artist’s artist. John Lennon, devoted to Conner’s work, famously sent him fan letters.

“Disturbing, indelible,” is one description of Connor’s body of work. He insisted that it’s “a social role for somebody to be called an artist.” Descriptions and reviews of his corpus have encompassed the whole spectrum of praise and blame. This is especially evident in "It’s All True," a 2016 retrospective of Conner’s work at the New York Museum of Modern Art.

“Disturbing, indelible,” is one description of Connor’s body of work. He insisted that it’s “a social role for somebody to be called an artist.” Descriptions and reviews of his corpus have encompassed the whole spectrum of praise and blame. This is especially evident in "It’s All True," a 2016 retrospective of Conner’s work at the New York Museum of Modern Art.

ADVERTISEMENT

From under the rug

While many attribute avant-garde and iconoclastic themes and imagery to Conner, his earliest works as a fresh Fine Arts graduate from the University of Nebraska had more mainstream leanings and were awarded by religious and corporate institutions in San Francisco in the late '50s.

While many attribute avant-garde and iconoclastic themes and imagery to Conner, his earliest works as a fresh Fine Arts graduate from the University of Nebraska had more mainstream leanings and were awarded by religious and corporate institutions in San Francisco in the late '50s.

It was at this point that he distanced himself from the popular art world. His first out-of-body experience, lying on the rug as an 11-year old in his birthplace of Kansas, floating out and around, before falling back into his body, would eventually inform the rest of his career and his approach to life as an artist and life as a whole. It was a mystical moment where he saw himself connected to the universe.

It was at this point that he distanced himself from the popular art world. His first out-of-body experience, lying on the rug as an 11-year old in his birthplace of Kansas, floating out and around, before falling back into his body, would eventually inform the rest of his career and his approach to life as an artist and life as a whole. It was a mystical moment where he saw himself connected to the universe.

When he left mainstream visual art, he pioneered such forms as found footage, as well as unique approaches to assemblage art. When he felt he had spent enough time with one medium, he would leave for good and jump to another. He was a true trailblazer—whatever he did, the art world was sure to follow.

When he left mainstream visual art, he pioneered such forms as found footage, as well as unique approaches to assemblage art. When he felt he had spent enough time with one medium, he would leave for good and jump to another. He was a true trailblazer—whatever he did, the art world was sure to follow.

This parallels the metamorphosis of the Mabuhay Gardens—more popularly known as the Fab Mab or simply the Mab, as it eventually transformed into a West Coast punk scene mecca. Musician and burlesque queen Mary Monday, whose regular act drew crowds to the Mab, recalls having to slowly convince Ness Aquino to let her shows continue. She eventually convinced him – not just by the good business being brought in, but by the showmanship as well.

This parallels the metamorphosis of the Mabuhay Gardens—more popularly known as the Fab Mab or simply the Mab, as it eventually transformed into a West Coast punk scene mecca. Musician and burlesque queen Mary Monday, whose regular act drew crowds to the Mab, recalls having to slowly convince Ness Aquino to let her shows continue. She eventually convinced him – not just by the good business being brought in, but by the showmanship as well.

Rock and camera roll

Hosting the Mab’s near-daily shows, the promoter Dirksen cut through the bull of formalities, and regularly insulted both artists and audience; this was part and parcel of his emceeing act. Arm-in-arm with a reticent Aquino, Dirksen’s bombastic style would bring even more acts to the joint, drawing British bands like The Clash and The Police, to make appearances. Eventually, he launched a regular TV broadcast.

Hosting the Mab’s near-daily shows, the promoter Dirksen cut through the bull of formalities, and regularly insulted both artists and audience; this was part and parcel of his emceeing act. Arm-in-arm with a reticent Aquino, Dirksen’s bombastic style would bring even more acts to the joint, drawing British bands like The Clash and The Police, to make appearances. Eventually, he launched a regular TV broadcast.

ADVERTISEMENT

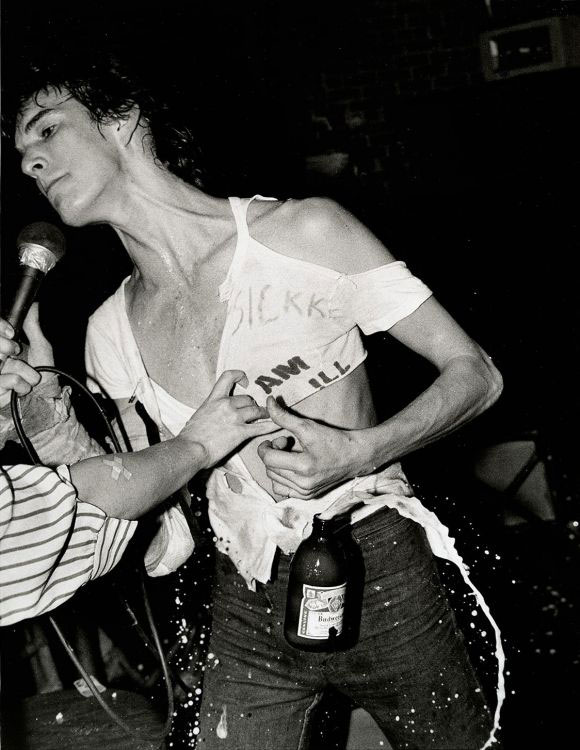

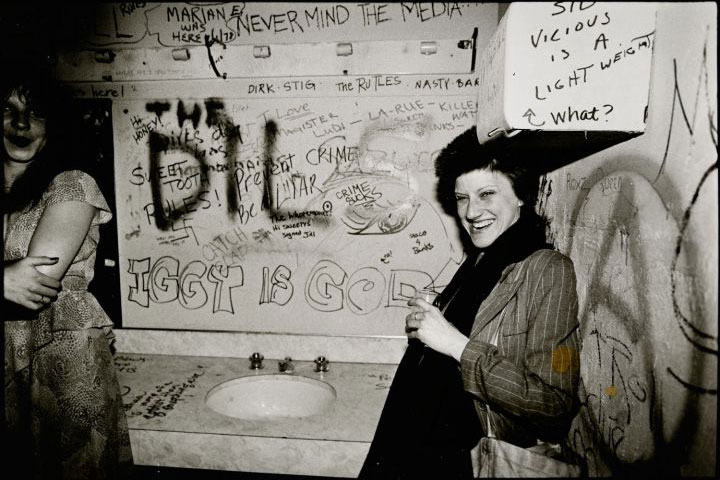

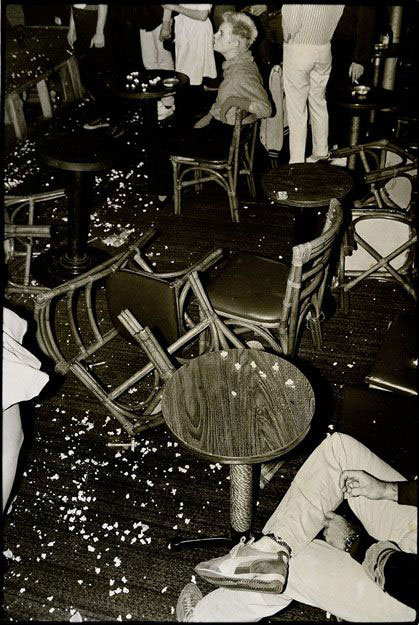

As the Mab drew more crowds, Conner, then 45, would become one of the regulars, dancing and moshing with the crowds and bands. He was now into photography—one of his more iconic works from that period is a series capturing the glorious grit of the San Francisco punk scene: spilled beer, torn shirts and toppled furniture. A chance encounter with magazine owner V. Vale, (in)famous for publishing the controversial Allen Ginsberg poem “Howl,” brought two creative forces together.

As the Mab drew more crowds, Conner, then 45, would become one of the regulars, dancing and moshing with the crowds and bands. He was now into photography—one of his more iconic works from that period is a series capturing the glorious grit of the San Francisco punk scene: spilled beer, torn shirts and toppled furniture. A chance encounter with magazine owner V. Vale, (in)famous for publishing the controversial Allen Ginsberg poem “Howl,” brought two creative forces together.

Conner’s now-famous photographs of the Mab’s nightly gigs were first published in Vale’s magazine Search & Destroy, which reported on the punk scene of the day. Rather than fossilize the energy of the scene, his photographs, often taken at the cost of grazed knees—better him than his camera – transmitted this energy to viewers.

He likened the experience of shooting the Mab’s regulars to sports and combat photography, reveling in the energy of his subjects. He described them as “floating in the air, part of this suspended sphere.” He further commented on “these beatific looks on their faces,” especially in the throes of anguish.

Conner’s now-famous photographs of the Mab’s nightly gigs were first published in Vale’s magazine Search & Destroy, which reported on the punk scene of the day. Rather than fossilize the energy of the scene, his photographs, often taken at the cost of grazed knees—better him than his camera – transmitted this energy to viewers.

He likened the experience of shooting the Mab’s regulars to sports and combat photography, reveling in the energy of his subjects. He described them as “floating in the air, part of this suspended sphere.” He further commented on “these beatific looks on their faces,” especially in the throes of anguish.

It was the ecstatic anguish of adrenaline: bodies and vocal chords strained by intense sets, sweat mingling with smoke and alcohol, lyrics and wailing guitars almost audible from the frozen portraits.

It was the ecstatic anguish of adrenaline: bodies and vocal chords strained by intense sets, sweat mingling with smoke and alcohol, lyrics and wailing guitars almost audible from the frozen portraits.

So hardcore

Interviews with him reveal a man who took care to distance art from the cult of personality usually associated with artists, often attributing his work to alter-egos such as Anonymous, Anonymouse, and Emily Feather. A rare photo of Conner in action shows him bending to capture a band’s performance, oblivious to anything but the act.

Interviews with him reveal a man who took care to distance art from the cult of personality usually associated with artists, often attributing his work to alter-egos such as Anonymous, Anonymouse, and Emily Feather. A rare photo of Conner in action shows him bending to capture a band’s performance, oblivious to anything but the act.

In one interview, Conner disclosed his stance on the art world’s “absurd requirement that only one personality can be present in an artist.” This was embodied by his movement across mediums—when the rest of the scene caught up with one genre, Conner was already packing up. Such was the spirit of punk, alive only in an atmosphere of spontaneity, grassroots organizing, and deviance from the norm.

In one interview, Conner disclosed his stance on the art world’s “absurd requirement that only one personality can be present in an artist.” This was embodied by his movement across mediums—when the rest of the scene caught up with one genre, Conner was already packing up. Such was the spirit of punk, alive only in an atmosphere of spontaneity, grassroots organizing, and deviance from the norm.

ADVERTISEMENT

This creative nomadism, from genre to persona changes, were not mere whimsies. Conner, like many punk artists, was cognizant of society’s tendency to commodify art. In the Mab, the middle-aged Conner wasn’t a man past his prime awkwardly reliving glory days; rather, this man who came into vogue at the Beat scene of the '50s had once again found kindred spirits more than 20 years later.

This creative nomadism, from genre to persona changes, were not mere whimsies. Conner, like many punk artists, was cognizant of society’s tendency to commodify art. In the Mab, the middle-aged Conner wasn’t a man past his prime awkwardly reliving glory days; rather, this man who came into vogue at the Beat scene of the '50s had once again found kindred spirits more than 20 years later.

The anger and disillusionment towards mass culture embodied itself in the generation’s countercultures. Punk was but one arm in a colony of scholars, musicians, filmmakers, poets, and critics all mingling in the underground scene. It’s a wonder all this was able to thrive right under Ness Aquino’s nose, and better judgment. Some might dismissively say it was all business for Aquino. Either way, it was happening, it was alive, and it was kicking.

The anger and disillusionment towards mass culture embodied itself in the generation’s countercultures. Punk was but one arm in a colony of scholars, musicians, filmmakers, poets, and critics all mingling in the underground scene. It’s a wonder all this was able to thrive right under Ness Aquino’s nose, and better judgment. Some might dismissively say it was all business for Aquino. Either way, it was happening, it was alive, and it was kicking.

Punk saved the Mabuhay Gardens, but the Mabuhay Gardens also helped save punk.

Punk saved the Mabuhay Gardens, but the Mabuhay Gardens also helped save punk.

A rebel’s legacy

It’s the inescapable fate of the contemporary to become history. The Mabuhay Gardens closed in 1986, a decade after the first punk show. Many of its regulars moved on to the mainstream music industry as the genre gained more recognition. In the words of some stalwarts, punk sold out. Vale eventually left the scene and Conner moved on to collage art.

It’s the inescapable fate of the contemporary to become history. The Mabuhay Gardens closed in 1986, a decade after the first punk show. Many of its regulars moved on to the mainstream music industry as the genre gained more recognition. In the words of some stalwarts, punk sold out. Vale eventually left the scene and Conner moved on to collage art.

The Mab’s DIY spirit however, inspired similar joints in the LA underground. Bruce Conner died in 2008 and yet his body of work continues to haunt and inspire contemporary artists and audiences.

The Mab’s DIY spirit however, inspired similar joints in the LA underground. Bruce Conner died in 2008 and yet his body of work continues to haunt and inspire contemporary artists and audiences.

ADVERTISEMENT

Punk, like most rock and roll, is a subculture forever on the verge of dying, but never quite needs total saving. Bruce Conner’s photographs—enabled by Ness Aquino’s openness to the beautiful and disturbing spirit of punk—captures that tragic and heroic spirit. It was never about him, it was always about the human stories that bled through all the black and white.

Punk, like most rock and roll, is a subculture forever on the verge of dying, but never quite needs total saving. Bruce Conner’s photographs—enabled by Ness Aquino’s openness to the beautiful and disturbing spirit of punk—captures that tragic and heroic spirit. It was never about him, it was always about the human stories that bled through all the black and white.

Bruce Conner’s legacy continues in his first retrospective exhibit in Southeast Asia, “Bruce Conner: Out Of Body,” ongoing up to June 3 at the Bellas Artes Outpost, Karrivin Plaza, Pasong Tamo Extension, Makati City. For inquires, visit http://bellasartesprojects.org.

Bruce Conner’s legacy continues in his first retrospective exhibit in Southeast Asia, “Bruce Conner: Out Of Body,” ongoing up to June 3 at the Bellas Artes Outpost, Karrivin Plaza, Pasong Tamo Extension, Makati City. For inquires, visit http://bellasartesprojects.org.

Special thanks to Bellas Artes Outpost for helping us acquire permission for the use of Connor’s photographs.

Special thanks to Bellas Artes Outpost for helping us acquire permission for the use of Connor’s photographs.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT