The best of times? Data debunk Marcos’s economic ‘golden years’ | ABS-CBN

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

The best of times? Data debunk Marcos’s economic ‘golden years’

The best of times? Data debunk Marcos’s economic ‘golden years’

Edson Joseph Guido and Che de los Reyes,

ABS-CBN Investigative and Research Group

Published Sep 21, 2017 08:10 AM PHT

|

Updated Nov 12, 2024 02:43 PM PHT

MANILA - Martial law under former President Ferdinand Marcos continues to stir spirited debates, 45 years since it was declared, as his heirs reassert national influence and human rights victims seek justice.

MANILA - Martial law under former President Ferdinand Marcos continues to stir spirited debates, 45 years since it was declared, as his heirs reassert national influence and human rights victims seek justice.

During the late strongman's 100th birth anniversary last Sept. 11, his son, former Sen. Ferdinand "Bongbong" Marcos Jr. said their family's history was "still being written."

During the late strongman's 100th birth anniversary last Sept. 11, his son, former Sen. Ferdinand "Bongbong" Marcos Jr. said their family's history was "still being written."

With 6 in every 10 Filipinos born after the Marcoses were ousted by a People Power uprising in 1986, their supporters insist they brought the economy to its golden years with growth reaching record highs and the peso almost at par with the dollar.

With 6 in every 10 Filipinos born after the Marcoses were ousted by a People Power uprising in 1986, their supporters insist they brought the economy to its golden years with growth reaching record highs and the peso almost at par with the dollar.

But for those who lived through the regime, like UP School of Economics Professor Emmanuel de Dios, such a view is distorted.

But for those who lived through the regime, like UP School of Economics Professor Emmanuel de Dios, such a view is distorted.

ADVERTISEMENT

The so-called good years were but a “flash in the pan" until the economy collapsed in the early 1980s

The so-called good years were but a “flash in the pan" until the economy collapsed in the early 1980s

“That’s why you cannot judge the Marcos regime only on the good side. You have to take the entire period,” De Dios said in an interview with the ABS-CBN Investigative and Research Group.

“That’s why you cannot judge the Marcos regime only on the good side. You have to take the entire period,” De Dios said in an interview with the ABS-CBN Investigative and Research Group.

"You did experience high growth in the early years, but you also experienced the worst recession in the latter years.”

"You did experience high growth in the early years, but you also experienced the worst recession in the latter years.”

The ABS-CBN Investigative and Research Group looked at key economic indicators during the Marcos years and compared them to the terms of other Philippines presidents, as well as other economies in the region.

The ABS-CBN Investigative and Research Group looked at key economic indicators during the Marcos years and compared them to the terms of other Philippines presidents, as well as other economies in the region.

RECORD PEAKS AND LOWS

Gross domestic product (GDP) growth peaked right after Marcos’s declaration of Martial law in 1972, reaching nearly 9 percent in 1973 and 1976, partly driven by a commodity boom when the prices of major Philippine commodity exports like coconut and sugar went up.

Gross domestic product (GDP) growth peaked right after Marcos’s declaration of Martial law in 1972, reaching nearly 9 percent in 1973 and 1976, partly driven by a commodity boom when the prices of major Philippine commodity exports like coconut and sugar went up.

ADVERTISEMENT

However, it was also under Marcos when the country hit the worst recession in history: a 7.3-percent contraction for 2 successive years in 1984 and 1985, as his grip on power waned.

However, it was also under Marcos when the country hit the worst recession in history: a 7.3-percent contraction for 2 successive years in 1984 and 1985, as his grip on power waned.

Average GDP growth during the Marcos years was at 3.8 percent, compared to 2.8 percent in the 1990s, 4.5 percent during the following decade, and 6.3 percent from 2010 to the present.

Average GDP growth during the Marcos years was at 3.8 percent, compared to 2.8 percent in the 1990s, 4.5 percent during the following decade, and 6.3 percent from 2010 to the present.

“From a purely historical record,” De Dios said, “You will see that the economy underwent great changes. The worst recession that the economy experienced in the post-war period. And it was his (Marcos’s) creation.”

“From a purely historical record,” De Dios said, “You will see that the economy underwent great changes. The worst recession that the economy experienced in the post-war period. And it was his (Marcos’s) creation.”

BORROWING SPREE

When oil-producing countries radically raised the prices of crude in the early ‘70s, they accumulated huge foreign exchange reserves that they needed to lend out because their economies could not absorb them, De Dios said. The so-called ‘petro-dollars’ became abundant — easily accessible at low interest rates.

When oil-producing countries radically raised the prices of crude in the early ‘70s, they accumulated huge foreign exchange reserves that they needed to lend out because their economies could not absorb them, De Dios said. The so-called ‘petro-dollars’ became abundant — easily accessible at low interest rates.

Marcos decided to go on a borrowing spree from mid-1970s to the early 1980s because of easy credit and low interest rates.

Marcos decided to go on a borrowing spree from mid-1970s to the early 1980s because of easy credit and low interest rates.

ADVERTISEMENT

From $4.1 billion in 1975, Philippine external debt doubled to $8.2 billion over two years and later ballooned to $24.4 billion in 1982.

From $4.1 billion in 1975, Philippine external debt doubled to $8.2 billion over two years and later ballooned to $24.4 billion in 1982.

This strategy of borrowing heavily was “peculiar to the Marcos period” and carried great risk, De Dios said. It “produced historically impressive growth,” but also “created the conditions for the big collapse later,” he added.

This strategy of borrowing heavily was “peculiar to the Marcos period” and carried great risk, De Dios said. It “produced historically impressive growth,” but also “created the conditions for the big collapse later,” he added.

TURNING POINT

The turning point came when the US entered a recession in the third quarter of 1981 and increased interest rates, bloating the cost of Philippine borrowings. Debt servicing then became very difficult for Manila, as with other debt-dependent countries in Latin America.

The turning point came when the US entered a recession in the third quarter of 1981 and increased interest rates, bloating the cost of Philippine borrowings. Debt servicing then became very difficult for Manila, as with other debt-dependent countries in Latin America.

The economy began to decline in 1981, proving debt-driven growth was unsustainable. The country’s exports at the time failed to keep pace with the ballooning debt.

The economy began to decline in 1981, proving debt-driven growth was unsustainable. The country’s exports at the time failed to keep pace with the ballooning debt.

“There could have been a different development path that was more stable, which is, you promote your exports,” he said.

“There could have been a different development path that was more stable, which is, you promote your exports,” he said.

ADVERTISEMENT

DEBT EXCEEDS EXPORTS

From 1978-1991, the country’s debt stood at more than 200 percent of exports, peaking in 1985 during the last full year of Marcos.

From 1978-1991, the country’s debt stood at more than 200 percent of exports, peaking in 1985 during the last full year of Marcos.

“Imagine, of your total exports, half of it or more would be going towards paying the debt only. You cannot use it for your imports,” De Dios said.

“Imagine, of your total exports, half of it or more would be going towards paying the debt only. You cannot use it for your imports,” De Dios said.

Other countries in the region, such as Thailand and Korea, did not borrow heavily despite the easy financing opportunities available, he said.

Other countries in the region, such as Thailand and Korea, did not borrow heavily despite the easy financing opportunities available, he said.

“And arguably, they fared better in the long run,” he said.

“And arguably, they fared better in the long run,” he said.

NINOY ASSASSINATION

The rise and fall of the economy during the Marcos years is likewise reflected in the GDP per capita, or each person’s share in economic output. It rose steadily from 1960 until the tail end of the Marcos regime, when it went down sharply.

The rise and fall of the economy during the Marcos years is likewise reflected in the GDP per capita, or each person’s share in economic output. It rose steadily from 1960 until the tail end of the Marcos regime, when it went down sharply.

ADVERTISEMENT

By 1982, per capita growth rate turned negative. The weakening economy and the succession problem brought about by Marcos’s deteriorating health were said to have prompted exiled opposition leader Benigno "Ninoy" Aquino Jr. to return to the country. But he was gunned down on the tarmac upon his arrival in Manila on August 21, 1983.

By 1982, per capita growth rate turned negative. The weakening economy and the succession problem brought about by Marcos’s deteriorating health were said to have prompted exiled opposition leader Benigno "Ninoy" Aquino Jr. to return to the country. But he was gunned down on the tarmac upon his arrival in Manila on August 21, 1983.

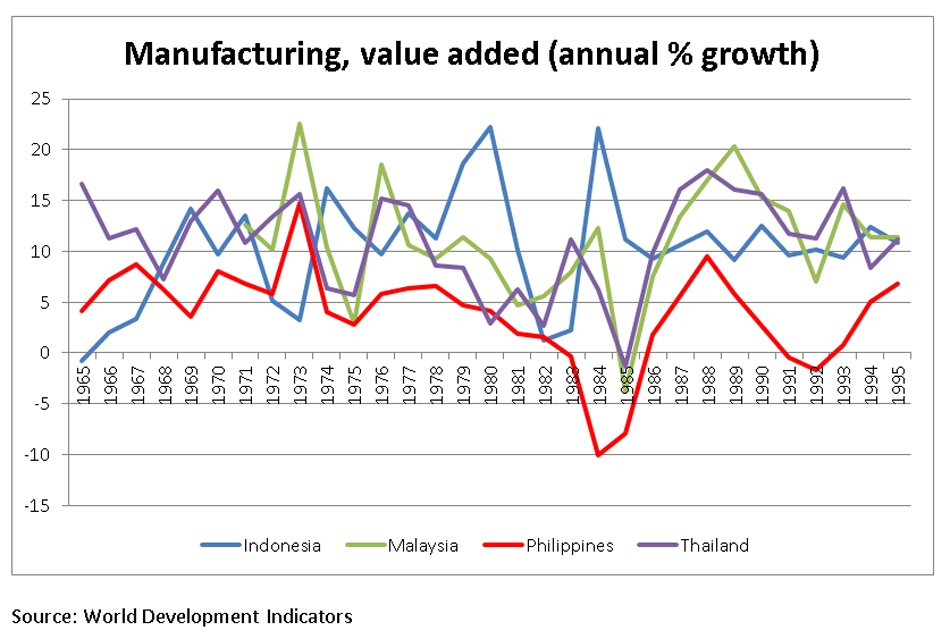

Aquino’s assassination sparked outrage and led to civil unrest, which was said to have turned off investors, particularly Japanese, Taiwanese, and Hong Kong companies that were looking to relocate their manufacturing operations in Southeast Asia in 1984.

Aquino’s assassination sparked outrage and led to civil unrest, which was said to have turned off investors, particularly Japanese, Taiwanese, and Hong Kong companies that were looking to relocate their manufacturing operations in Southeast Asia in 1984.

These companies instead turned to Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand, jumpstarting what would become vibrant manufacturing sectors in those countries.

These companies instead turned to Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand, jumpstarting what would become vibrant manufacturing sectors in those countries.

The Philippines missed this opportunity to industrialize and develop its economy because of the political uncertainty during the Marcos administration, which could not have happened at a worse time, according to De Dios and Jeffrey Williamson in their 2014 analysis “Has the Philippines forever lost its chance at industrialization?”

The Philippines missed this opportunity to industrialize and develop its economy because of the political uncertainty during the Marcos administration, which could not have happened at a worse time, according to De Dios and Jeffrey Williamson in their 2014 analysis “Has the Philippines forever lost its chance at industrialization?”

The country was left far behind by its neighbors. While the country’s GDP per capita increased nearly three times from 1960 to 2016, Thailand’s GDP per capita had a 10-fold increase, Malaysia’s increased nearly eight-fold, and Indonesia’s increased nearly six times.

The country was left far behind by its neighbors. While the country’s GDP per capita increased nearly three times from 1960 to 2016, Thailand’s GDP per capita had a 10-fold increase, Malaysia’s increased nearly eight-fold, and Indonesia’s increased nearly six times.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Philippines lost more than two decades of economic development. It was only in 2004 when the country was able to surpass its 1982 GDP per capita level and recover from the economic downturn during the Marcos administration.

The Philippines lost more than two decades of economic development. It was only in 2004 when the country was able to surpass its 1982 GDP per capita level and recover from the economic downturn during the Marcos administration.

De Dios said not all of it was Marcos’s doing.

De Dios said not all of it was Marcos’s doing.

“Other administrations also had a role,” such as the energy crisis in the 1990s, he said.

“Other administrations also had a role,” such as the energy crisis in the 1990s, he said.

Examining economic output alone, however, does not give a complete picture of how life was like for Filipinos during the Marcos years. One also has to look at the impact of Marcos’s economic policies on the prices of goods, wages, and quality of jobs.

Examining economic output alone, however, does not give a complete picture of how life was like for Filipinos during the Marcos years. One also has to look at the impact of Marcos’s economic policies on the prices of goods, wages, and quality of jobs.

WEAKER PESO

The petro-dollars, which were previously abundant, dwindled in the early ‘80s and caused financing institutions to tighten international credit, making it difficult for the Philippines to obtain long-term loans.

The petro-dollars, which were previously abundant, dwindled in the early ‘80s and caused financing institutions to tighten international credit, making it difficult for the Philippines to obtain long-term loans.

ADVERTISEMENT

The government had to find other sources of financing to service its debts and import goods and raw materials. The country had no choice but to acquire short-term loans despite the higher interest rates that such carry.

The government had to find other sources of financing to service its debts and import goods and raw materials. The country had no choice but to acquire short-term loans despite the higher interest rates that such carry.

Aquino’s assassination in 1983 and the mounting political instability, however, prompted financing institutions to shut down credit lines to the Philippines, and to demand quick repayment of the county’s short-term debts. Eventually, the government ran out of international reserves to service its debt and had to declare a moratorium on its debt payments by October that same year.

Aquino’s assassination in 1983 and the mounting political instability, however, prompted financing institutions to shut down credit lines to the Philippines, and to demand quick repayment of the county’s short-term debts. Eventually, the government ran out of international reserves to service its debt and had to declare a moratorium on its debt payments by October that same year.

The International Monetary Fund did provide additional financing to the Philippines in 1984, but this came with severe conditions. One of them was the further devaluation of the peso, which was already weakening from 1969-1970 when it plummeted from P3.92 to P6.02 against the dollar.

The International Monetary Fund did provide additional financing to the Philippines in 1984, but this came with severe conditions. One of them was the further devaluation of the peso, which was already weakening from 1969-1970 when it plummeted from P3.92 to P6.02 against the dollar.

By 1982, the peso was at P8.54 to the dollar. IMF’s conditions further pushed the peso down to P16.70 in1984. The following year, as Marcos’s rule was drawing to a close, the peso fell further down to P18.61 to the dollar.

By 1982, the peso was at P8.54 to the dollar. IMF’s conditions further pushed the peso down to P16.70 in1984. The following year, as Marcos’s rule was drawing to a close, the peso fell further down to P18.61 to the dollar.

WANTED: MORE JOBS

With the depletion of the country’s international reserves, limited funds were available to import raw materials for several industries, resulting in cuts in production and subsequently in manpower, and later in shutdown of companies.

With the depletion of the country’s international reserves, limited funds were available to import raw materials for several industries, resulting in cuts in production and subsequently in manpower, and later in shutdown of companies.

ADVERTISEMENT

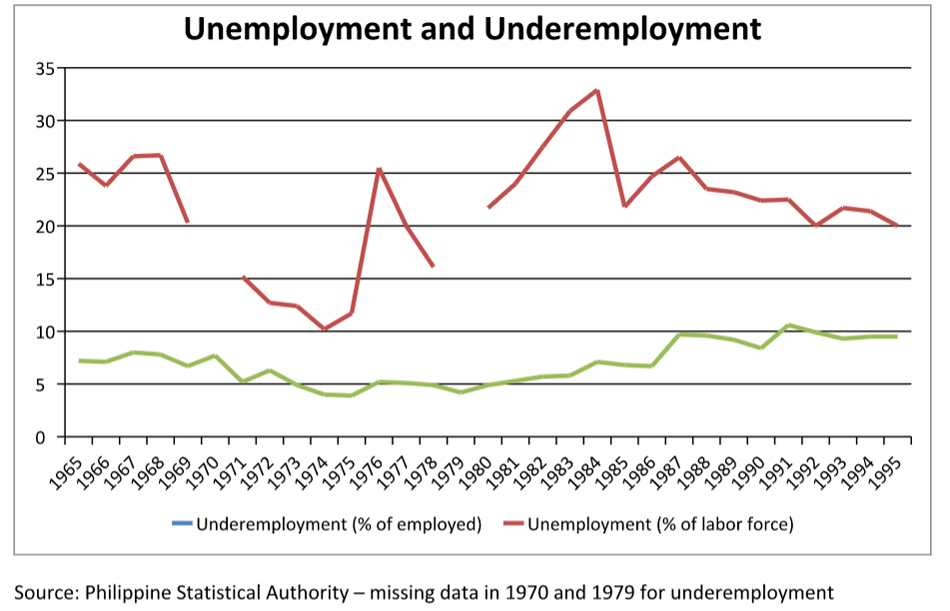

With firms closing shop or cutting back on costs, underemployment peaked at 33 percent in 1984. This meant that more than 3 out of every 10 people who had a job either wanted to work more hours or were looking for additional jobs, but could not find any.

With firms closing shop or cutting back on costs, underemployment peaked at 33 percent in 1984. This meant that more than 3 out of every 10 people who had a job either wanted to work more hours or were looking for additional jobs, but could not find any.

Even if unemployment was lower during the Marcos administration compared to that of other presidents, the jobs available were not enough to satisfy the workers’ needs.

Even if unemployment was lower during the Marcos administration compared to that of other presidents, the jobs available were not enough to satisfy the workers’ needs.

RISING PRICES, DWINDLING INCOMES

With less production, and with imports becoming more expensive due to a weaker peso, the supply of goods dwindled, driving up the prices of food, fuel, and other goods with large import content so much so that by 1984, inflation shot up to a record 50 percent.

With less production, and with imports becoming more expensive due to a weaker peso, the supply of goods dwindled, driving up the prices of food, fuel, and other goods with large import content so much so that by 1984, inflation shot up to a record 50 percent.

People then found out that they could buy less with their income than they did in previous years.

People then found out that they could buy less with their income than they did in previous years.

By 1985, the last full year of the Marcos administration, the real wage rate for unskilled workers plummeted to 23.21 from 86.02 in 1966. The real wage rate for skilled workers, meanwhile, dropped from 112.9 to 35.55 in the same period.

By 1985, the last full year of the Marcos administration, the real wage rate for unskilled workers plummeted to 23.21 from 86.02 in 1966. The real wage rate for skilled workers, meanwhile, dropped from 112.9 to 35.55 in the same period.

ADVERTISEMENT

This meant that if an unskilled worker had a wage of P100 in 1966, by 1985, that same wage would only allow him to buy the equivalent of P27 worth of goods. That was equivalent to a 73 percent decrease in real terms of the amount of goods and services.

This meant that if an unskilled worker had a wage of P100 in 1966, by 1985, that same wage would only allow him to buy the equivalent of P27 worth of goods. That was equivalent to a 73 percent decrease in real terms of the amount of goods and services.

CRONYISM AND CORRUPTION

Debt-driven growth, De Dios said, is not necessarily bad as long as the money is invested in productive sectors that will fuel growth.

Debt-driven growth, De Dios said, is not necessarily bad as long as the money is invested in productive sectors that will fuel growth.

But it wasn’t so for the Philippines as the borrowings were invested in projects that yielded little or no cash returns—no foreign exchange to sustain the economy.

But it wasn’t so for the Philippines as the borrowings were invested in projects that yielded little or no cash returns—no foreign exchange to sustain the economy.

“A lot of them were white elephants,” he said. “A lot of them were not even investment projects but luxury spending.”

“A lot of them were white elephants,” he said. “A lot of them were not even investment projects but luxury spending.”

He cited as an example Imelda Marcos’s “hotel building spree,” which was part of a “huge effort that didn’t earn foreign exchange.”

He cited as an example Imelda Marcos’s “hotel building spree,” which was part of a “huge effort that didn’t earn foreign exchange.”

ADVERTISEMENT

For De Dios, the Philippine government at the time was akin to a person who goes on a spending spree using a credit card.

For De Dios, the Philippine government at the time was akin to a person who goes on a spending spree using a credit card.

“You have a good life while you’re living on credit, but you suffer after that,” he said.

“You have a good life while you’re living on credit, but you suffer after that,” he said.

And suffer Filipinos did as a result of Marcos’s economic decisions. As the peso depreciated, companies closed down, prices went up and people could buy less with their incomes. Those who already had jobs felt the pressure to find additional work, but none were available.

And suffer Filipinos did as a result of Marcos’s economic decisions. As the peso depreciated, companies closed down, prices went up and people could buy less with their incomes. Those who already had jobs felt the pressure to find additional work, but none were available.

De Dios said cronyism and corruption got in the way.

De Dios said cronyism and corruption got in the way.

“The irony of it is that in the midst of the debt crisis, ’84-’85, namimili pa ng apartments si Imelda sa New York,” he said.

“The irony of it is that in the midst of the debt crisis, ’84-’85, namimili pa ng apartments si Imelda sa New York,” he said.

ADVERTISEMENT

Based on "purely economics," De Dios said the "last decade or so" was the best for the economy, spanning former presidents Gloria Arroyo, Benigno "Noynoy" Aquino and incumbent Rodrigo Duterte.

Based on "purely economics," De Dios said the "last decade or so" was the best for the economy, spanning former presidents Gloria Arroyo, Benigno "Noynoy" Aquino and incumbent Rodrigo Duterte.

“[Marcos] is an interesting part of history, but he’s history. ‘Yung iniluwa mo, ‘wag mo nang kainin," De Dios said.

“[Marcos] is an interesting part of history, but he’s history. ‘Yung iniluwa mo, ‘wag mo nang kainin," De Dios said.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT