The culinary icon Doreen Fernandez once lived in this charming Silay bed and breakfast

ADVERTISEMENT

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

The culinary icon Doreen Fernandez once lived in this charming Silay bed and breakfast

JEROME GOMEZ

Published Dec 08, 2022 02:24 PM PHT

|

Updated Dec 17, 2022 04:52 PM PHT

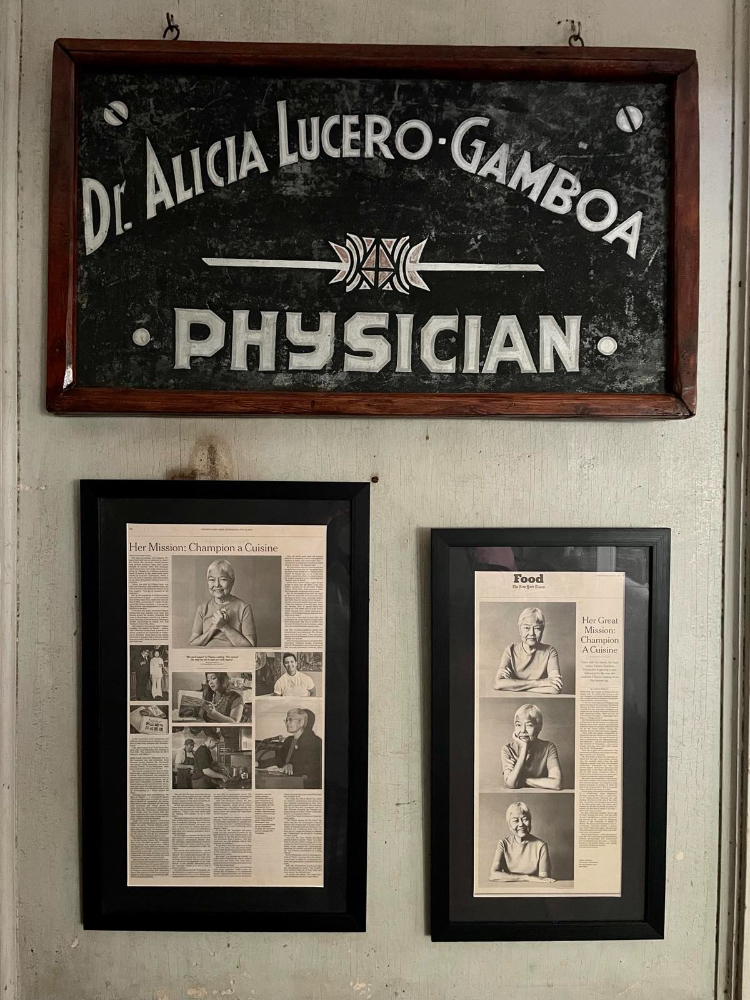

It’s easily one of the more inviting ancestral homes in idyllic Silay City, this two-level American Colonial-style structure in 5 Rizal Street. Built by the Negrense haciendero Aguinaldo Gamboa and his doctor wife Alicia Lucero before the war, it is now run by their talented and affable granddaughter Reena as a bed and breakfast. Called Casa A. Gamboa, it’s a six-bedroom affair with a big front garden where there’s always a spread of delicious dishes the family grew up with.

It’s easily one of the more inviting ancestral homes in idyllic Silay City, this two-level American Colonial-style structure in 5 Rizal Street. Built by the Negrense haciendero Aguinaldo Gamboa and his doctor wife Alicia Lucero before the war, it is now run by their talented and affable granddaughter Reena as a bed and breakfast. Called Casa A. Gamboa, it’s a six-bedroom affair with a big front garden where there’s always a spread of delicious dishes the family grew up with.

There’s history in this home. It was once occupied by a Japanese colonel before it became the headquarters of the 5th Division commanded by a Major General Rupp Brush. A photograph of General Douglas MacArthur coming down the house’s front steps is displayed proudly on the porch, asserting the address’ importance in Negros’ storied past.

There’s history in this home. It was once occupied by a Japanese colonel before it became the headquarters of the 5th Division commanded by a Major General Rupp Brush. A photograph of General Douglas MacArthur coming down the house’s front steps is displayed proudly on the porch, asserting the address’ importance in Negros’ storied past.

According to the memoirs of Reena’s father Danilo Lucero Gamboa, MacArthur once drove into the property with his men, their vehicles trampling on the Gamboa matriarch’s lovingly tended gumamelas that lined the driveway. The young Danilo was told the general was quite angry that day and called for a conference in one of the rooms. After the huddle—where the homeowners were not invited—MacArthur, as planned, received his fifth or sixth Silver Star medal on the front lawn and left soon after. There’s no mention of apologies for the blooms trampled upon.

According to the memoirs of Reena’s father Danilo Lucero Gamboa, MacArthur once drove into the property with his men, their vehicles trampling on the Gamboa matriarch’s lovingly tended gumamelas that lined the driveway. The young Danilo was told the general was quite angry that day and called for a conference in one of the rooms. After the huddle—where the homeowners were not invited—MacArthur, as planned, received his fifth or sixth Silver Star medal on the front lawn and left soon after. There’s no mention of apologies for the blooms trampled upon.

It doesn’t sound like the best story to represent a house that is the picture of warmth and gentility. And between two iconic figures that once walked these grounds, it’s the other icon, really, the lady who wrote beautifully and earnestly about Filipino food, who is the more fitting personality to associate with the B and B: Doreen Gamboa Fernandez, the late food critic, author of the beloved book “Tikim,” and “groundbreaking culinary ethnographer who transformed the way Filipinos saw their food,” as the New York Times once described her.

It doesn’t sound like the best story to represent a house that is the picture of warmth and gentility. And between two iconic figures that once walked these grounds, it’s the other icon, really, the lady who wrote beautifully and earnestly about Filipino food, who is the more fitting personality to associate with the B and B: Doreen Gamboa Fernandez, the late food critic, author of the beloved book “Tikim,” and “groundbreaking culinary ethnographer who transformed the way Filipinos saw their food,” as the New York Times once described her.

ADVERTISEMENT

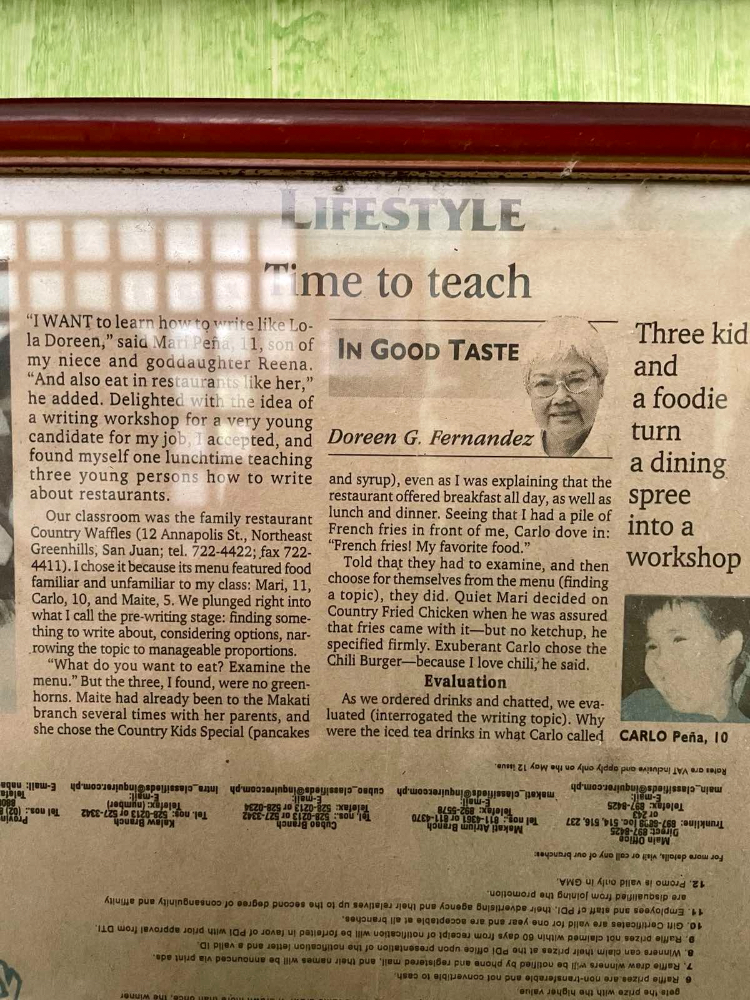

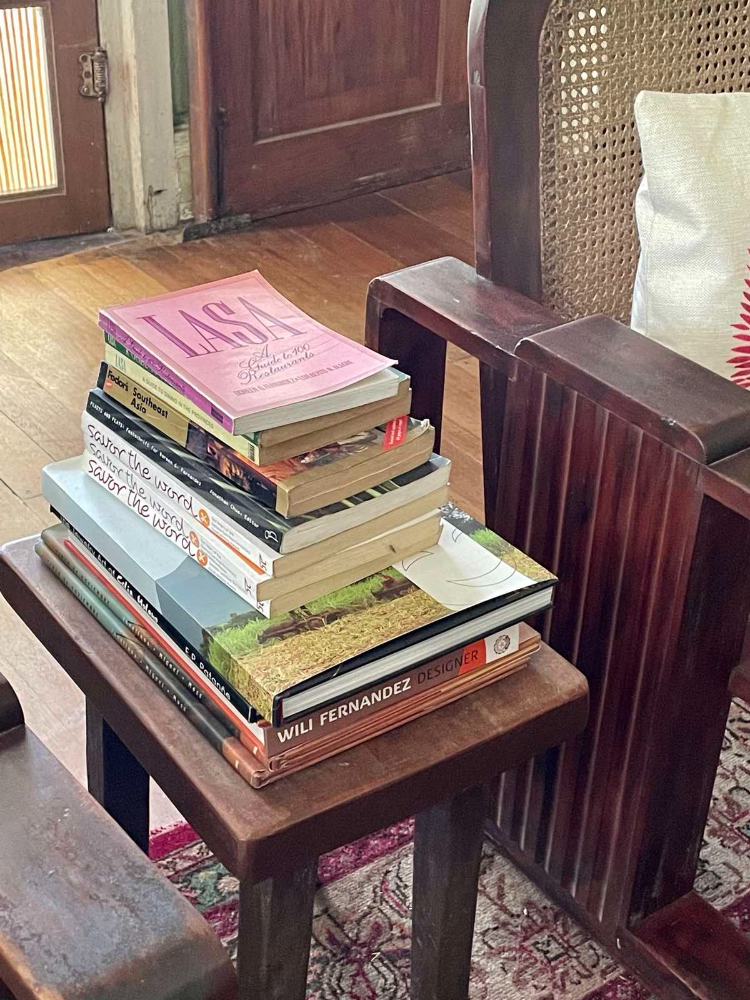

Good thing her presence is undeniable in the living room, dotted as it is with Doreen mementos: the New York Times feature on her by Ligaya Mishan elegantly framed and hanging on a wall under a vintage wooden signage announcing her mother’s medical services (“Dr. Alicia Lucero Gamboa, Physician”); a couple of her In Good Taste columns in the Inquirer, framed in glass as well, one of them about a day spent at Country Waffles teaching Reena’s kids how to write a food review (“We plunged right into what I call the pre-writing stage: finding something to write about, considering options, narrowing the topic to manageable proportions”); a copy of “Lasa: A Guide to 100 Restaurants” on top of a pile of books on a side table; and a portrait of Doreen on one of the shelves, beside a portrait of Reena done in the similar style. Reena is Doreen’s niece and inaanak.

Good thing her presence is undeniable in the living room, dotted as it is with Doreen mementos: the New York Times feature on her by Ligaya Mishan elegantly framed and hanging on a wall under a vintage wooden signage announcing her mother’s medical services (“Dr. Alicia Lucero Gamboa, Physician”); a couple of her In Good Taste columns in the Inquirer, framed in glass as well, one of them about a day spent at Country Waffles teaching Reena’s kids how to write a food review (“We plunged right into what I call the pre-writing stage: finding something to write about, considering options, narrowing the topic to manageable proportions”); a copy of “Lasa: A Guide to 100 Restaurants” on top of a pile of books on a side table; and a portrait of Doreen on one of the shelves, beside a portrait of Reena done in the similar style. Reena is Doreen’s niece and inaanak.

The eldest daughter of Aguinaldo and Alicia Gamboa, Doreen lived in this very abode, albeit briefly when she was a child, before the Second World War forced the Gamboas out of it and forced them to move to the family farm by the river, close to an air-raid shelter. Many decades later, she would spend time in the property as a guest, sometimes visiting with friends like the writer Gilda Cordero Fernando and the esteemed publisher Eggie Apostol and their husbands; other times working on some of her books, among them the groundbreaking “Kinilaw: A Philippine Cuisine of Freshness” which she co-authored with Edilberto Alegre and published in 1991.

The eldest daughter of Aguinaldo and Alicia Gamboa, Doreen lived in this very abode, albeit briefly when she was a child, before the Second World War forced the Gamboas out of it and forced them to move to the family farm by the river, close to an air-raid shelter. Many decades later, she would spend time in the property as a guest, sometimes visiting with friends like the writer Gilda Cordero Fernando and the esteemed publisher Eggie Apostol and their husbands; other times working on some of her books, among them the groundbreaking “Kinilaw: A Philippine Cuisine of Freshness” which she co-authored with Edilberto Alegre and published in 1991.

“When she started writing books, for most of her original research, she would come here all the time [to do them],” recalls Reena. “Me naman [I was] going around with her.”

“When she started writing books, for most of her original research, she would come here all the time [to do them],” recalls Reena. “Me naman [I was] going around with her.”

Doreen spent time here while doing research for “Kinilaw.” Although she would mostly stay at the house of Reena’s parents, the residence next to Casa A. Gamboa located within the same property. It was a house designed by her husband, the architect Wili Fernandez.

Doreen spent time here while doing research for “Kinilaw.” Although she would mostly stay at the house of Reena’s parents, the residence next to Casa A. Gamboa located within the same property. It was a house designed by her husband, the architect Wili Fernandez.

Reena recalls Doreen always had a notebook and tape recorder with her. “Her best friend, Sophie Marañon Cueva, who is from a powerful political family in Sagay, would bring all of us to their island. That’s when Tita Doreen met Enting.” Enting is Enting Lobaton, a local legend. The famous kinilaw master who would become a star of Doreen’s and Ed’s book.

Reena recalls Doreen always had a notebook and tape recorder with her. “Her best friend, Sophie Marañon Cueva, who is from a powerful political family in Sagay, would bring all of us to their island. That’s when Tita Doreen met Enting.” Enting is Enting Lobaton, a local legend. The famous kinilaw master who would become a star of Doreen’s and Ed’s book.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Tita Doreen was always a jolly person, always sharing what she knew, always the teacher,” recalls Reena of the food writer. “I would just listen to her talk animatedly about how fascinated she was with Enting.”

“Tita Doreen was always a jolly person, always sharing what she knew, always the teacher,” recalls Reena of the food writer. “I would just listen to her talk animatedly about how fascinated she was with Enting.”

Doreen was very much fond of Reena that she wanted to adopt her (the Fernandezes were childless). “But my dad didn’t want so she treated all of us [nephews and nieces] like her own.” Doreen would bring each child out to lunch and engage with each one. “She likes to know how you are, what you’re thinking, what your life is like. She’s really nice.”

Doreen was very much fond of Reena that she wanted to adopt her (the Fernandezes were childless). “But my dad didn’t want so she treated all of us [nephews and nieces] like her own.” Doreen would bring each child out to lunch and engage with each one. “She likes to know how you are, what you’re thinking, what your life is like. She’s really nice.”

The bed and breakfast proprietress recalls her aunt’s food-related activities with the women in her family. “She and my mom would go to the Silay market sometimes because she enjoyed discovering whatever is sold in the market,” offers Reena. “I remember basta she is home, we have to buy the head of the alimusan na paksiw from Sir, a famous carinderia here in Silay. It has batwan in it. She and my grandmother would always put on their eyeglasses just to be able to eat the head properly and enjoy all its flavors.” Alimusan is an eel-tailed catfish usually found in Bago City.

The bed and breakfast proprietress recalls her aunt’s food-related activities with the women in her family. “She and my mom would go to the Silay market sometimes because she enjoyed discovering whatever is sold in the market,” offers Reena. “I remember basta she is home, we have to buy the head of the alimusan na paksiw from Sir, a famous carinderia here in Silay. It has batwan in it. She and my grandmother would always put on their eyeglasses just to be able to eat the head properly and enjoy all its flavors.” Alimusan is an eel-tailed catfish usually found in Bago City.

These days when Reena mentions her Tita’s name to visitors, she is saddened some of them no longer remember who Doreen was. A funny thing because elsewhere in the world, Filipino-Americans exploring their culinary roots and making waves in the international food scene continue to seek out whatever’s available of her writings.

These days when Reena mentions her Tita’s name to visitors, she is saddened some of them no longer remember who Doreen was. A funny thing because elsewhere in the world, Filipino-Americans exploring their culinary roots and making waves in the international food scene continue to seek out whatever’s available of her writings.

But there’s no question Doreen’s spirit burns bright in Silay’s 5 Rizal Street. Not just because her books and clippings and likeness are on Casa A. Gamboa’s tables and walls and shelves, but because Reena and her mother, whether they acknowledge it or not, has somehow kept Doreen’s love and respect for Filipino food alive, too, just by honoring their homegrown cuisine.

But there’s no question Doreen’s spirit burns bright in Silay’s 5 Rizal Street. Not just because her books and clippings and likeness are on Casa A. Gamboa’s tables and walls and shelves, but because Reena and her mother, whether they acknowledge it or not, has somehow kept Doreen’s love and respect for Filipino food alive, too, just by honoring their homegrown cuisine.

ADVERTISEMENT

Lyn Gamboa is a bit of a culinary figure in Negros having founded its annual Adobo Festival. And Reena is an active member of the province’s Slow Food community, advocating for the use of the province’s “ark of taste ingredients”—endangered heritage food that are sustainably produced, unique in their flavors and distinct to the area.

Lyn Gamboa is a bit of a culinary figure in Negros having founded its annual Adobo Festival. And Reena is an active member of the province’s Slow Food community, advocating for the use of the province’s “ark of taste ingredients”—endangered heritage food that are sustainably produced, unique in their flavors and distinct to the area.

And of course there’s the food she and her battery of kitchen hands prepare for guests at the Casa. On our visit, she served comfort food familiar to many Panay natives, with ingredients that are sourced from the island and pulled from her farm.

And of course there’s the food she and her battery of kitchen hands prepare for guests at the Casa. On our visit, she served comfort food familiar to many Panay natives, with ingredients that are sourced from the island and pulled from her farm.

There’s inubaran manok, or free range chicken with ubad or pith of banana. There’s ensaladang langka with gata and an adobo-flavored sotanghon. And then the most comforting dish of all: grilled liempo—made special by a side dish of delicious pickled kamias in olive oil which could be an ulam in itself, a recipe she learned from her ex-mother in law. They’re not heirloom recipes, Reena is quick to say—just dishes that have been part of big and small Gamboa gatherings over the decades.

There’s inubaran manok, or free range chicken with ubad or pith of banana. There’s ensaladang langka with gata and an adobo-flavored sotanghon. And then the most comforting dish of all: grilled liempo—made special by a side dish of delicious pickled kamias in olive oil which could be an ulam in itself, a recipe she learned from her ex-mother in law. They’re not heirloom recipes, Reena is quick to say—just dishes that have been part of big and small Gamboa gatherings over the decades.

Reena is not a cook but it must be amazing the spreads she gets to regularly curate and whip up—if the spread she prepared for us is any indication. From the aforementioned dishes to the whimsical tablescape she put together: the laminated paper chargers she makes herself (she has a workshop/gift shop on the basement), the clear glass tableware with gold trim, foliage and flowers likely from the very garden that surrounded us, all set against a table cloth of an exuberant, tropical, painterly print. It’s hard to have a bad meal in Negros, but our dinner at Casa A. Gamboa was definitely a special and memorable one.

Reena is not a cook but it must be amazing the spreads she gets to regularly curate and whip up—if the spread she prepared for us is any indication. From the aforementioned dishes to the whimsical tablescape she put together: the laminated paper chargers she makes herself (she has a workshop/gift shop on the basement), the clear glass tableware with gold trim, foliage and flowers likely from the very garden that surrounded us, all set against a table cloth of an exuberant, tropical, painterly print. It’s hard to have a bad meal in Negros, but our dinner at Casa A. Gamboa was definitely a special and memorable one.

At breakfast, we imagined ourselves the writer Doreen in the sunlight-dappled Gamboa dining room, surrounded by her niece’s collection of joyful artworks, enjoying dried fish and fried rice—the writer’s favorites, we were told. Except our meal also involved scrambled eggs with kamatis and sibuyas, and garlicky, savory Chorizo de Bacolod from the island’s Ereñata-Manalotos. It was our last day in Negros and it was a meal that reminded us we needed to take our time. And so we did, with a leisurely conversation with Reena, a special order of hot chocolate, and a plate of the Casa’s boquerones the lady of the house wanted us to taste. “Perhaps one does have to get away from the city and the workaday,” Doreen wrote in “Tikim,” “to have breakfasts that sing the morning awake.”

At breakfast, we imagined ourselves the writer Doreen in the sunlight-dappled Gamboa dining room, surrounded by her niece’s collection of joyful artworks, enjoying dried fish and fried rice—the writer’s favorites, we were told. Except our meal also involved scrambled eggs with kamatis and sibuyas, and garlicky, savory Chorizo de Bacolod from the island’s Ereñata-Manalotos. It was our last day in Negros and it was a meal that reminded us we needed to take our time. And so we did, with a leisurely conversation with Reena, a special order of hot chocolate, and a plate of the Casa’s boquerones the lady of the house wanted us to taste. “Perhaps one does have to get away from the city and the workaday,” Doreen wrote in “Tikim,” “to have breakfasts that sing the morning awake.”

ADVERTISEMENT

By honoring her hometown dishes with nothing less but love and creativity, it wouldn’t be wrong to say Reena is keeping alive the legacy of her Tita Doreen, a lady who also doesn’t cook but has made us regard Filipino food the way we’ve never done before.

By honoring her hometown dishes with nothing less but love and creativity, it wouldn’t be wrong to say Reena is keeping alive the legacy of her Tita Doreen, a lady who also doesn’t cook but has made us regard Filipino food the way we’ve never done before.

Visit Casa A. Gamboa on Facebook and Instagram.

Visit Casa A. Gamboa on Facebook and Instagram.

Read More:

anc

ancx

ancx.ph

abs-cbn

abs-cbn news

food and drink

feature

casa a. gamboa

reena gamboa

ancx featured

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT