Japan's way of tea is a lesson in rituals and emptying oneself | ABS-CBN

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

Japan's way of tea is a lesson in rituals and emptying oneself

Japan's way of tea is a lesson in rituals and emptying oneself

David Celdran

Published Nov 13, 2018 07:18 AM PHT

Ritual tea drinking, known as chanoyu or the “way of tea,” was introduced in Japan from China, but came into its own as a spiritual practice when it was adopted by Zen Buddhism in the 15th century. Influenced by Zen, the ceremonial preparation of powdered green tea or matcha symbolized the purity of the spiritual world.

Ritual tea drinking, known as chanoyu or the “way of tea,” was introduced in Japan from China, but came into its own as a spiritual practice when it was adopted by Zen Buddhism in the 15th century. Influenced by Zen, the ceremonial preparation of powdered green tea or matcha symbolized the purity of the spiritual world.

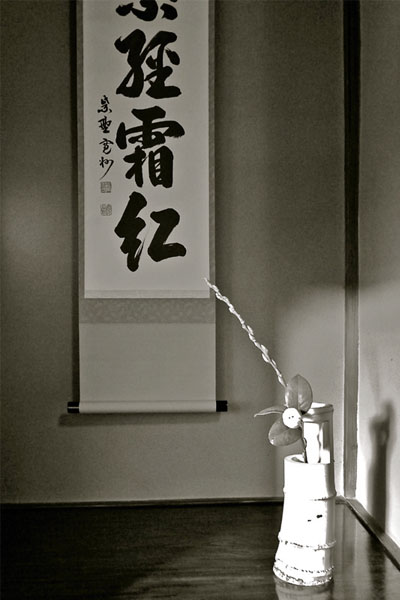

It was Sen no Rikyu in particular, a 17th-century Zen monk and the greatest tea master of Japan, who transformed the ceremony and perfected it as a vehicle for expressing wabi. He replaced the highly decorative Chinese utensils, popular in the tea-drinking sessions of the elite, and substituted these for simple and natural objects. Rikyu’s application of wabi also influenced the art and architecture associated with the tea ceremony: calligraphy, flower arrangement, and most notably, the design of the tea house and tea garden.

It was Sen no Rikyu in particular, a 17th-century Zen monk and the greatest tea master of Japan, who transformed the ceremony and perfected it as a vehicle for expressing wabi. He replaced the highly decorative Chinese utensils, popular in the tea-drinking sessions of the elite, and substituted these for simple and natural objects. Rikyu’s application of wabi also influenced the art and architecture associated with the tea ceremony: calligraphy, flower arrangement, and most notably, the design of the tea house and tea garden.

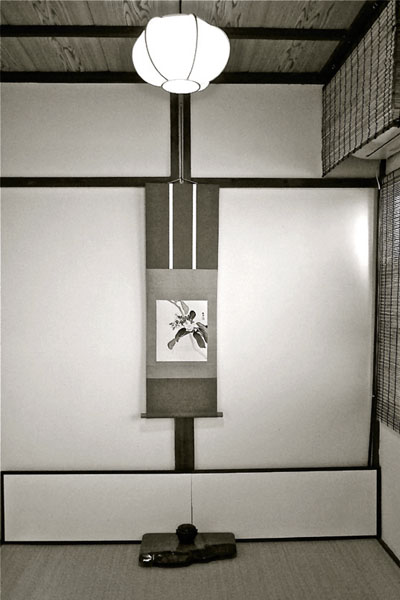

The tea room reflects both the austerity of wabi and the Buddhist philosophy of emptying oneself. An authentic tea room is without any furniture or decorations, except for a hanging scroll and flower arrangement in the alcove. Conversation inside the room is kept to a minimum, and the only sound one hears is that of boiling water in the kettle and the whisking of tea.

The tea room reflects both the austerity of wabi and the Buddhist philosophy of emptying oneself. An authentic tea room is without any furniture or decorations, except for a hanging scroll and flower arrangement in the alcove. Conversation inside the room is kept to a minimum, and the only sound one hears is that of boiling water in the kettle and the whisking of tea.

Tea ceremonies in Kyoto today are interpreted liberally, but the traditional “way of tea” can only be practiced in a proper tea house under the supervision of a trained tea master. The ritual of preparing and serving the tea is just as important as drinking the tea itself, and a formal session can take up to four hours to complete. The ceremony also requires a strict code of ethics that is often incomprehensible to foreigners and younger Japanese.

Tea ceremonies in Kyoto today are interpreted liberally, but the traditional “way of tea” can only be practiced in a proper tea house under the supervision of a trained tea master. The ritual of preparing and serving the tea is just as important as drinking the tea itself, and a formal session can take up to four hours to complete. The ceremony also requires a strict code of ethics that is often incomprehensible to foreigners and younger Japanese.

ADVERTISEMENT

The tea ceremony begins long before the guests arrive. The tea master waters the garden, decorates the alcove, and starts the fire for the kettle. Tea kaiseki—a lighter version of the elaborate multi-course meal common in Kyoto—and traditional sweets to accompany the tea are likewise prepared in advance.

The tea ceremony begins long before the guests arrive. The tea master waters the garden, decorates the alcove, and starts the fire for the kettle. Tea kaiseki—a lighter version of the elaborate multi-course meal common in Kyoto—and traditional sweets to accompany the tea are likewise prepared in advance.

Guests approach the teahouse from the garden but are first required to purify themselves by washing their hands and rinsing their mouths at the stone washbasin along the path. Once “purified” and inside the tearoom, participants of the ceremony are required to kneel seiza style—with legs and feet tucked under the thighs. Guests are encouraged to admire the austere beauty of the tea room and the hand-painted scroll in the alcove, while the tea master begins the graceful ritual of purifying the utensils. Once cleansed, the tea master scoops powdered green tea into the ceramic bowl and whisks it into a thick and foamy brew. (In more formal ceremonies, the tea preparation takes place only after a tea kaiseki meal is served.)

Guests approach the teahouse from the garden but are first required to purify themselves by washing their hands and rinsing their mouths at the stone washbasin along the path. Once “purified” and inside the tearoom, participants of the ceremony are required to kneel seiza style—with legs and feet tucked under the thighs. Guests are encouraged to admire the austere beauty of the tea room and the hand-painted scroll in the alcove, while the tea master begins the graceful ritual of purifying the utensils. Once cleansed, the tea master scoops powdered green tea into the ceramic bowl and whisks it into a thick and foamy brew. (In more formal ceremonies, the tea preparation takes place only after a tea kaiseki meal is served.)

The climax of the ceremony is the offering of tea to guests. Etiquette requires receiving the bowl with the right hand and placing it on the palm with the left, before rotating it thrice in a clockwise direction. Experienced guests take a bit of time to admire the beauty of the bowl before taking a sip, making sure to wipe the rim of the bowl with the hand, and rotating the bowl back to its original position before passing it on to the next person in the room.

The climax of the ceremony is the offering of tea to guests. Etiquette requires receiving the bowl with the right hand and placing it on the palm with the left, before rotating it thrice in a clockwise direction. Experienced guests take a bit of time to admire the beauty of the bowl before taking a sip, making sure to wipe the rim of the bowl with the hand, and rotating the bowl back to its original position before passing it on to the next person in the room.

Every step of the ceremony is rich in symbolism, and it takes multiple visits to a tea house to perfect the rituals. A wise tea master will make it a point to emphasize the essence of the ceremony rather than its formal procedures. Indeed, at the heart of the “way of tea,” is ichi-go ichi-e, a reminder that each experience must be treasured, as it can never be replicated. No matter how clumsily one goes through a tea ceremony, Kyoto’s beloved tradition is guaranteed to be a once in a lifetime experience.

Every step of the ceremony is rich in symbolism, and it takes multiple visits to a tea house to perfect the rituals. A wise tea master will make it a point to emphasize the essence of the ceremony rather than its formal procedures. Indeed, at the heart of the “way of tea,” is ichi-go ichi-e, a reminder that each experience must be treasured, as it can never be replicated. No matter how clumsily one goes through a tea ceremony, Kyoto’s beloved tradition is guaranteed to be a once in a lifetime experience.

Photographs by David Celdran

This story first appeared in Vault Magazine Vol 5 2012.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT