25 years after: Amy Besa & Romy Dorotan on the pains and glory of being New York restaurateurs | ABS-CBN

ADVERTISEMENT

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

25 years after: Amy Besa & Romy Dorotan on the pains and glory of being New York restaurateurs

25 years after: Amy Besa & Romy Dorotan on the pains and glory of being New York restaurateurs

NANA OZAETA

Published Aug 23, 2020 09:45 AM PHT

|

Updated Aug 28, 2020 02:16 PM PHT

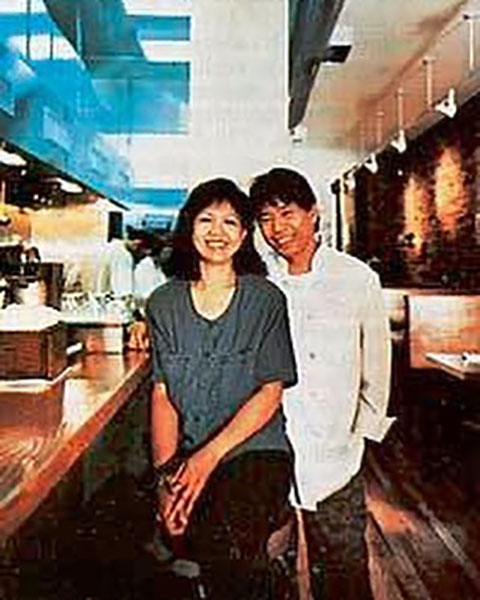

When talking about the emergence of Philippine cuisine in the United States, two names stand out: Amy Besa and Romy Dorotan. Both Philippine-born and bred, they separately immigrated to the United States in the 1970s, met and married, and in 1995, opened their first restaurant called Cendrillon (“Cinderella” in French, named after a ballet) in Soho, New York City.

When talking about the emergence of Philippine cuisine in the United States, two names stand out: Amy Besa and Romy Dorotan. Both Philippine-born and bred, they separately immigrated to the United States in the 1970s, met and married, and in 1995, opened their first restaurant called Cendrillon (“Cinderella” in French, named after a ballet) in Soho, New York City.

I remember dining there early on and marveling at its beautiful setting, its familiar menu of adobo, lumpia, ukoy, and the hospitality of its owners. As the chef, Dorotan held court in the kitchen, while Besa took care of guests with her warm presence and infectious laugh. Restaurant critics and food writers heaped praise on Cendrillon, with many New Yorkers “discovering” Filipino food for the first time.

I remember dining there early on and marveling at its beautiful setting, its familiar menu of adobo, lumpia, ukoy, and the hospitality of its owners. As the chef, Dorotan held court in the kitchen, while Besa took care of guests with her warm presence and infectious laugh. Restaurant critics and food writers heaped praise on Cendrillon, with many New Yorkers “discovering” Filipino food for the first time.

The couple went on to publish the award-winning Memories of Philippine Kitchens in 2006. They then closed down Cendrillon and subsequently moved to Brooklyn in 2009 to open Purple Yam (the English name for ube, of course).

The couple went on to publish the award-winning Memories of Philippine Kitchens in 2006. They then closed down Cendrillon and subsequently moved to Brooklyn in 2009 to open Purple Yam (the English name for ube, of course).

While they’ve established themselves in the United States, Besa and Dorotan have kept in touch with their Philippine roots, shuttling back and forth regularly since the early 2000s. They concretized that connection by opening Purple Yam Malate in Besa’s old family home in 2014. They hadn’t been back to the Philippines since 2018 though—and then the pandemic happened.

While they’ve established themselves in the United States, Besa and Dorotan have kept in touch with their Philippine roots, shuttling back and forth regularly since the early 2000s. They concretized that connection by opening Purple Yam Malate in Besa’s old family home in 2014. They hadn’t been back to the Philippines since 2018 though—and then the pandemic happened.

ADVERTISEMENT

Just last August 16, Besa and Dorotan marked the 25th anniversary of Cendrillon by posting about it in their Purple Yam Brooklyn Facebook account. It has been that long since they embarked on this journey. And it was as good an opportunity as any for me to touch base via online chat with this couple who are ever passionate about Filipino food, and about serving and engaging with their community.

Just last August 16, Besa and Dorotan marked the 25th anniversary of Cendrillon by posting about it in their Purple Yam Brooklyn Facebook account. It has been that long since they embarked on this journey. And it was as good an opportunity as any for me to touch base via online chat with this couple who are ever passionate about Filipino food, and about serving and engaging with their community.

ANCX: What was the reaction when you posted about Cendrillon’s 25 years?

ANCX: What was the reaction when you posted about Cendrillon’s 25 years?

Besa: You should see all the outpourings of people reminiscing. We have a Purple Yam Brooklyn page on Facebook, my personal page, and my Instagram page. Iba iba ang nagsasalita. Nakakaiyak talaga. I didn’t know that these people appreciated us… People were telling me, ‘You remember that time when you let us in but you were closed.’ Sorry, I don’t remember but I’m glad we did. And then somebody else said, ‘You came by and took care of my baby, so I could eat my buko pie.’

Besa: You should see all the outpourings of people reminiscing. We have a Purple Yam Brooklyn page on Facebook, my personal page, and my Instagram page. Iba iba ang nagsasalita. Nakakaiyak talaga. I didn’t know that these people appreciated us… People were telling me, ‘You remember that time when you let us in but you were closed.’ Sorry, I don’t remember but I’m glad we did. And then somebody else said, ‘You came by and took care of my baby, so I could eat my buko pie.’

ANCX: You mention in your post you had some of the happiest times there. What made Cendrillon so special?

ANCX: You mention in your post you had some of the happiest times there. What made Cendrillon so special?

Besa: I think a lot of it has to do with what Cendrillon physically was. It was this huge space. It was about 1,750 square feet in area, including the kitchen, and there were three distinct areas, the front with the banquettes, then that row of booths, and then that big room at the back with a skylight. You could hang out there for a long time and be very comfortable. It was really our home and we made a lot of friends. So to me, that was the happiest part of our 13 1/2 years there, our friends that we made. Most of them are still with us at Purple Yam. And they’re not just customers, they’re friends.

Besa: I think a lot of it has to do with what Cendrillon physically was. It was this huge space. It was about 1,750 square feet in area, including the kitchen, and there were three distinct areas, the front with the banquettes, then that row of booths, and then that big room at the back with a skylight. You could hang out there for a long time and be very comfortable. It was really our home and we made a lot of friends. So to me, that was the happiest part of our 13 1/2 years there, our friends that we made. Most of them are still with us at Purple Yam. And they’re not just customers, they’re friends.

ANCX: Romy, you didn’t really cook Filipino food before, at least not professionally?

ANCX: Romy, you didn’t really cook Filipino food before, at least not professionally?

Dorotan: When we started Cendrillon, I didn’t really know much about Filipino food. When we started the menus, we really based it on Amy’s home cooking and my recollection of other Filipino food.

Dorotan: When we started Cendrillon, I didn’t really know much about Filipino food. When we started the menus, we really based it on Amy’s home cooking and my recollection of other Filipino food.

ANCX: But you got criticized for your take on Filipino food?

ANCX: But you got criticized for your take on Filipino food?

Dorotan: I was always fascinated by what people say, that we are not authentic. It’s the basic classic way of doing [Filipino]. There are other dishes that we tweak, like the fresh lumpia, we put ube wrapper, but basically it’s the same. We didn’t really change it. People say we were fusion, but the origins of it is what I would call authentic traditional Filipino food… We use good ingredients and that’s the basis of our recollection of what we eat at home. This is what adobo is, hindi matamis. It’s suka from the sourness and all that. So yeah, I think I had a really hard time explaining that we are authentic in that sense. To my mind, authenticity means that you use the essence of good ingredients.

Dorotan: I was always fascinated by what people say, that we are not authentic. It’s the basic classic way of doing [Filipino]. There are other dishes that we tweak, like the fresh lumpia, we put ube wrapper, but basically it’s the same. We didn’t really change it. People say we were fusion, but the origins of it is what I would call authentic traditional Filipino food… We use good ingredients and that’s the basis of our recollection of what we eat at home. This is what adobo is, hindi matamis. It’s suka from the sourness and all that. So yeah, I think I had a really hard time explaining that we are authentic in that sense. To my mind, authenticity means that you use the essence of good ingredients.

ADVERTISEMENT

Besa: For example, we notice that a lot of people who use this acetic acid from the factory, they put sugar in their adobo. I guess to replace the sweetness of fruits and palms. We don’t put sugar in our adobo. What sweetens our adobo is coconut milk which is very sweet in itself. Then a lot of people [say], ‘Oh you know that’s not authentic.’ We had people screaming and yelling at us a long time ago. ‘Do not put coconut milk in your adobo,’ screaming at us on the phone! I asked these people, have you been to Bicol? No! Have you been to the Visayas? No! Like they put coconut milk there, in everything!

Besa: For example, we notice that a lot of people who use this acetic acid from the factory, they put sugar in their adobo. I guess to replace the sweetness of fruits and palms. We don’t put sugar in our adobo. What sweetens our adobo is coconut milk which is very sweet in itself. Then a lot of people [say], ‘Oh you know that’s not authentic.’ We had people screaming and yelling at us a long time ago. ‘Do not put coconut milk in your adobo,’ screaming at us on the phone! I asked these people, have you been to Bicol? No! Have you been to the Visayas? No! Like they put coconut milk there, in everything!

Dorotan: Remember, we started doing all these ube products. I used to make ube lumpia wrapper.

Dorotan: Remember, we started doing all these ube products. I used to make ube lumpia wrapper.

ANCX: That’s right, before ube became super popular.

ANCX: That’s right, before ube became super popular.

Besa: Before, nobody paid attention to ube. I remember Ruth Reichl was the first New York Times critic to give us a review, and then she made this comment that the problem with our ube ice cream was it was too light. It was like lavender but it should really be bright purple. We got criticized because we did not put food coloring!

Besa: Before, nobody paid attention to ube. I remember Ruth Reichl was the first New York Times critic to give us a review, and then she made this comment that the problem with our ube ice cream was it was too light. It was like lavender but it should really be bright purple. We got criticized because we did not put food coloring!

ANCX: Unfortunately, a lot of people don’t know how to tell!

ANCX: Unfortunately, a lot of people don’t know how to tell!

Besa: The unfortunate thing about it now is that it seems with the popularity of ube, there are a lot of farms in California claiming their purple sweet potato is ube… I guess when you get popularity like that, you’ll have to take the bad with the good. I don’t care if you use fake stuff as long as you acknowledge it.

Besa: The unfortunate thing about it now is that it seems with the popularity of ube, there are a lot of farms in California claiming their purple sweet potato is ube… I guess when you get popularity like that, you’ll have to take the bad with the good. I don’t care if you use fake stuff as long as you acknowledge it.

ANCX: You were happy at Cendrillon, so why close down?

ANCX: You were happy at Cendrillon, so why close down?

Besa: Our landlords were pressuring us for years. Even before our lease was up, they would hammer it in, ‘Your rent is so low.’ It’s not low, but compared to what was happening to the area... They had rent envy because we got the lease before the area exploded. So by the last few years of our stay there, it was hell… Since our lease was up, they wanted to triple it. We were paying $10,000 at the time, so they wanted like $35,000 a month, and then everything was failing around us because there was a recession; 2008 was the biggest financial meltdown we’ve had. And so many spaces were empty in Soho.

Besa: Our landlords were pressuring us for years. Even before our lease was up, they would hammer it in, ‘Your rent is so low.’ It’s not low, but compared to what was happening to the area... They had rent envy because we got the lease before the area exploded. So by the last few years of our stay there, it was hell… Since our lease was up, they wanted to triple it. We were paying $10,000 at the time, so they wanted like $35,000 a month, and then everything was failing around us because there was a recession; 2008 was the biggest financial meltdown we’ve had. And so many spaces were empty in Soho.

ADVERTISEMENT

ANCX: How did Romy take the decision to not renew the lease?

ANCX: How did Romy take the decision to not renew the lease?

Besa: (laughs) I had to drag Romy out of there kicking and screaming!

Besa: (laughs) I had to drag Romy out of there kicking and screaming!

ANCX: What was your last day like?

ANCX: What was your last day like?

Besa: It was so poignant the last night that we were there. It was just Romy and me there, everything empty. We were sitting in this empty booth, and two of our closest friends who live in the neighborhood came in and dropped by. We spent the last hours together, sitting in the booth, with no table, pretending that it was a regular service. It was so sad but it was also very nice. It was very sweet that we spent those last few hours there with friends who are still very, very close friends today. But then, to tell you the truth, when we left, I was just so happy to go.

Besa: It was so poignant the last night that we were there. It was just Romy and me there, everything empty. We were sitting in this empty booth, and two of our closest friends who live in the neighborhood came in and dropped by. We spent the last hours together, sitting in the booth, with no table, pretending that it was a regular service. It was so sad but it was also very nice. It was very sweet that we spent those last few hours there with friends who are still very, very close friends today. But then, to tell you the truth, when we left, I was just so happy to go.

ANCX: In retrospect, how do you see Cendrillon in terms of its contribution to the Filipino food movement in the United States?

ANCX: In retrospect, how do you see Cendrillon in terms of its contribution to the Filipino food movement in the United States?

Besa: I really do not like when people make pronouncements, when so and so started modern Filipino cuisine, or they were the first to do that. I really disagree when people say things like that because that means they do not understand the historicity of cooking and eating our traditional foods. Because it’s a line, a continuous line, nobody started it.

Besa: I really do not like when people make pronouncements, when so and so started modern Filipino cuisine, or they were the first to do that. I really disagree when people say things like that because that means they do not understand the historicity of cooking and eating our traditional foods. Because it’s a line, a continuous line, nobody started it.

For me, the Filipino food movement started the moment Filipinos set foot in this country and started cooking for themselves. We are just part of that line. And there’s no such thing as we started this or someone started it. What we did was we put in our own interpretation.

For me, the Filipino food movement started the moment Filipinos set foot in this country and started cooking for themselves. We are just part of that line. And there’s no such thing as we started this or someone started it. What we did was we put in our own interpretation.

I remember when we did our cookbook, Memories of Philippine Kitchens, and we already had Cendrillon at that time. We did that book tour and we went to California and other places in the US… When we would have launch meetings with the [Filipino] community, there was that palpable sense of anger with some people against the turo turos, those greasy diners that Filipinos started with. And there were some people who would actually almost want me to disown and condemn these turo turos and greasy diners as a stain on Filipino cooking.

I remember when we did our cookbook, Memories of Philippine Kitchens, and we already had Cendrillon at that time. We did that book tour and we went to California and other places in the US… When we would have launch meetings with the [Filipino] community, there was that palpable sense of anger with some people against the turo turos, those greasy diners that Filipinos started with. And there were some people who would actually almost want me to disown and condemn these turo turos and greasy diners as a stain on Filipino cooking.

ADVERTISEMENT

They’re part of our history… They fed the community, they provided a service, otherwise people would die if they didn’t, because of loneliness or homesickness. Filipinos were facing a lot of racism and prejudice in this country. Filipinos were not allowed to enter some restaurants. We were not allowed to get married to white people. Food was a source of comfort and something to hang on to, so whatever they did, they fed the enclave, they fed the community.

They’re part of our history… They fed the community, they provided a service, otherwise people would die if they didn’t, because of loneliness or homesickness. Filipinos were facing a lot of racism and prejudice in this country. Filipinos were not allowed to enter some restaurants. We were not allowed to get married to white people. Food was a source of comfort and something to hang on to, so whatever they did, they fed the enclave, they fed the community.

We came out of the turo turo heritage and we’re just part of that line. And the future generations will do something else, but they will have built on what we did just like what we did. We built on what Elvie’s turo turo did and all those restaurants paved the way for us.

We came out of the turo turo heritage and we’re just part of that line. And the future generations will do something else, but they will have built on what we did just like what we did. We built on what Elvie’s turo turo did and all those restaurants paved the way for us.

When we came in, it was the time that we wanted to bring [Filipino food] out of the enclave and bring it now out into the open, into the mainstream, which had its own challenges. It wasn’t easy, a lot of people would walk in and ask if we were Japanese, if we were Thai, because those were the accepted [cuisines]. And a lot of people would walk out if we said no, this is Filipino. But then, you just have to make friends. The moment people get to know you personally, then they’ll accept everything, then they’ll look at the food, they’ll look at it from your point of view and they will love it because it’s good. That’s part of the process.

When we came in, it was the time that we wanted to bring [Filipino food] out of the enclave and bring it now out into the open, into the mainstream, which had its own challenges. It wasn’t easy, a lot of people would walk in and ask if we were Japanese, if we were Thai, because those were the accepted [cuisines]. And a lot of people would walk out if we said no, this is Filipino. But then, you just have to make friends. The moment people get to know you personally, then they’ll accept everything, then they’ll look at the food, they’ll look at it from your point of view and they will love it because it’s good. That’s part of the process.

Dorotan: I think we had a big impact in terms of Filipino food.

Dorotan: I think we had a big impact in terms of Filipino food.

Besa: Yeah. You don’t think of it. It just comes back at you because now, as I said, all those messages, just like one of them [on my Instagram] from Dominic Ainza, a Filipino chef based in San Francisco, he said ‘You are the reason I do what I do.’ Iyak na naman ako! And I liked what he said: ‘Because not only the passion for food, but for love of community you have.’

Besa: Yeah. You don’t think of it. It just comes back at you because now, as I said, all those messages, just like one of them [on my Instagram] from Dominic Ainza, a Filipino chef based in San Francisco, he said ‘You are the reason I do what I do.’ Iyak na naman ako! And I liked what he said: ‘Because not only the passion for food, but for love of community you have.’

ADVERTISEMENT

ANCX: And you seem to have continued that with Purple Yam. How have you been doing so far with the pandemic?

ANCX: And you seem to have continued that with Purple Yam. How have you been doing so far with the pandemic?

Besa: I really, really thought that we would never reopen when we closed on March 18. The city said, starting March 16, no more dine in, just take out. So on March 16 and 17, we tried takeout, and you know, we did like $200 one day, and then the next day was wow, 100% increase. We made $400! And I said it’s not worth it. For $400 a day, you’re paying thousands a day for utilities, rent, and all that. Tapos baka ma COVID ka pa, so we just said, you know what, let’s close.

Besa: I really, really thought that we would never reopen when we closed on March 18. The city said, starting March 16, no more dine in, just take out. So on March 16 and 17, we tried takeout, and you know, we did like $200 one day, and then the next day was wow, 100% increase. We made $400! And I said it’s not worth it. For $400 a day, you’re paying thousands a day for utilities, rent, and all that. Tapos baka ma COVID ka pa, so we just said, you know what, let’s close.

ANCX: And you were ready to throw in the towel and just close for good?

ANCX: And you were ready to throw in the towel and just close for good?

Besa: Romy had prostate cancer. He had radiation treatment last year. So he has an underlying condition even though it’s okay now and prostate cancer is very treatable. But we’re 70 [years old] so I mean, we’ve already lived our lives. We’re not like 30 years old!

Besa: Romy had prostate cancer. He had radiation treatment last year. So he has an underlying condition even though it’s okay now and prostate cancer is very treatable. But we’re 70 [years old] so I mean, we’ve already lived our lives. We’re not like 30 years old!

ANCX: But you ended up still opening in July.

ANCX: But you ended up still opening in July.

Besa: It was Romy who decided that.

Besa: It was Romy who decided that.

Dorotan: Amy doesn’t go out so I’ve been out a couple of days. I saw our street Cortelyou Road was really alive during that time, all this sidewalk and backyard seating. People were really having fun, lalo na yung mga bars. Buhay na buhay yung calle, parang may street fair or market.

Dorotan: Amy doesn’t go out so I’ve been out a couple of days. I saw our street Cortelyou Road was really alive during that time, all this sidewalk and backyard seating. People were really having fun, lalo na yung mga bars. Buhay na buhay yung calle, parang may street fair or market.

ANCX: Romy, how were you able to convince Amy to just go ahead and open?

ANCX: Romy, how were you able to convince Amy to just go ahead and open?

Dorotan: I just ignored her. For the first time! (followed by raucous laughter from Besa)

Dorotan: I just ignored her. For the first time! (followed by raucous laughter from Besa)

ADVERTISEMENT

Besa: We reopened July 18. It was so shocking because, absence pala really makes the heart grow fonder. Ang dami daming dumadating. What was good was we could now do backyard and sidewalk seating—as long as you’re not indoors. So that really made it a lot better. So there are days now we almost do like what we used to do before.

Besa: We reopened July 18. It was so shocking because, absence pala really makes the heart grow fonder. Ang dami daming dumadating. What was good was we could now do backyard and sidewalk seating—as long as you’re not indoors. So that really made it a lot better. So there are days now we almost do like what we used to do before.

Dorotan: Before we opened, we thought we would just limit our choices. Tapos tinitingnan ko yung menu, ano kaya ang iaalis ko dito? Wala naman akong masyadong maalis. Because most of the restaurants I’ve seen, talagang limited ang mga menu nila.

Dorotan: Before we opened, we thought we would just limit our choices. Tapos tinitingnan ko yung menu, ano kaya ang iaalis ko dito? Wala naman akong masyadong maalis. Because most of the restaurants I’ve seen, talagang limited ang mga menu nila.

Besa: We took out maybe some salads, which just goes to show you, right? (laughs) Even the Korean dishes get ordered: Jap Chae, Pa Jun, and the dumplings, yun talagang gustong gustong gusto ng mga tao iyon. But then the Ukoy, the Lechon Kawali, the Adobo are always there. Adobo, you will never kill adobo!

Besa: We took out maybe some salads, which just goes to show you, right? (laughs) Even the Korean dishes get ordered: Jap Chae, Pa Jun, and the dumplings, yun talagang gustong gustong gusto ng mga tao iyon. But then the Ukoy, the Lechon Kawali, the Adobo are always there. Adobo, you will never kill adobo!

ANCX: You’re hopeful New York can contain the virus?

ANCX: You’re hopeful New York can contain the virus?

Besa: So far it’s been contained. We’ve had protests for Black Lives Matter and people are eating out. I’m really glad that they’ve maintained it… Now I don’t know what will happen during winter. Because we can no longer seat people outside. So unless we are allowed to have indoor dining, patay na naman iyan… The only way I can see it is if we will probably have to put some plexiglass dividers, so that they can prevent the virus from spreading around the room.

Besa: So far it’s been contained. We’ve had protests for Black Lives Matter and people are eating out. I’m really glad that they’ve maintained it… Now I don’t know what will happen during winter. Because we can no longer seat people outside. So unless we are allowed to have indoor dining, patay na naman iyan… The only way I can see it is if we will probably have to put some plexiglass dividers, so that they can prevent the virus from spreading around the room.

ANCX: But for the time being, things are good in your part of town?

ANCX: But for the time being, things are good in your part of town?

Besa: Before in normal times, a neighborhood restaurant was disadvantaged, as opposed to those restaurants situated in downtown Manhattan where you have the subway, where you have a ton of people coming in and out for office. Now, that’s totally deserted… Now, the advantage of being in a neighborhood is very obvious because people work at home. And they’re willing to come and pick up their food because nandiyan lang sila. After 11 years, my judgment of opening up in this neighborhood proved good. After 11 years! (laughs)

Besa: Before in normal times, a neighborhood restaurant was disadvantaged, as opposed to those restaurants situated in downtown Manhattan where you have the subway, where you have a ton of people coming in and out for office. Now, that’s totally deserted… Now, the advantage of being in a neighborhood is very obvious because people work at home. And they’re willing to come and pick up their food because nandiyan lang sila. After 11 years, my judgment of opening up in this neighborhood proved good. After 11 years! (laughs)

ADVERTISEMENT

ANCX: Your customers must be so happy to have you back open.

ANCX: Your customers must be so happy to have you back open.

Besa: There’s one particular post on Instagram that said, ‘I went back to Purple Yam a few weeks ago and it was the first time I felt normal. I was crying after eating your food with my friends. I was in tears.’ So I started crying also! [It said] ‘Oh, thank you for being an oasis.’ Parang they feel like home. That’s the theme that I get. They’re like at home.

Besa: There’s one particular post on Instagram that said, ‘I went back to Purple Yam a few weeks ago and it was the first time I felt normal. I was crying after eating your food with my friends. I was in tears.’ So I started crying also! [It said] ‘Oh, thank you for being an oasis.’ Parang they feel like home. That’s the theme that I get. They’re like at home.

Photos courtesy of Amy Besa, Romy Doroton, and Purple Yam Brooklyn on Facebook

Pancit luglug and Purple Yam sidewalk photos by Catherine Colton

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT