How we kill: Notes on the death penalty in the Philippines (Part 2) | ABS-CBN

Welcome, Kapamilya! We use cookies to improve your browsing experience. Continuing to use this site means you agree to our use of cookies. Tell me more!

How we kill: Notes on the death penalty in the Philippines (Part 2)

How we kill: Notes on the death penalty in the Philippines (Part 2)

Joel F. Ariate Jr,

VERA Files

Published Jul 14, 2019 02:23 PM PHT

(Second of 2 parts)

(Second of 2 parts)

Killing Them Softly

The history of the death penalty in the Philippines in the 20th century is the history of the state’s pursuit to clinically execute convicts. The political leaders may all have wanted to act tough on criminals, yet, in the execution chamber, the functionaries of the state went to great lengths to relieve or mask the pain for the convict in the course of an execution.

The history of the death penalty in the Philippines in the 20th century is the history of the state’s pursuit to clinically execute convicts. The political leaders may all have wanted to act tough on criminals, yet, in the execution chamber, the functionaries of the state went to great lengths to relieve or mask the pain for the convict in the course of an execution.

They did not always succeed.

They did not always succeed.

Hanging is supposed to kill convicts not by choking them to death, but by breaking their neck during the drop. But as described in John White’s account, it became an excruciating ordeal, with at least three people humping, and pulling at, the convict’s body just to ensure a quick death.

Hanging is supposed to kill convicts not by choking them to death, but by breaking their neck during the drop. But as described in John White’s account, it became an excruciating ordeal, with at least three people humping, and pulling at, the convict’s body just to ensure a quick death.

ADVERTISEMENT

The garrote is supposed to be an improvement on hanging. Instead of breaking the neck in an unsure manner, the garrote, at a turn of a screw, will snap the spinal cord and detach the neck from the skull, leading to instantaneous death.

The garrote is supposed to be an improvement on hanging. Instead of breaking the neck in an unsure manner, the garrote, at a turn of a screw, will snap the spinal cord and detach the neck from the skull, leading to instantaneous death.

As with hanging, the actual practice differed from the mechanical calculations. An account by Felix Roxas, a curious child in the closing days of the Spanish empire, recalled seeing the faces of convicts on public display after being garroted with “protruding tongues” and “open eyes” bearing the marks not of snapped spinal cord but of “strangled necks.”

As with hanging, the actual practice differed from the mechanical calculations. An account by Felix Roxas, a curious child in the closing days of the Spanish empire, recalled seeing the faces of convicts on public display after being garroted with “protruding tongues” and “open eyes” bearing the marks not of snapped spinal cord but of “strangled necks.”

The electric chair

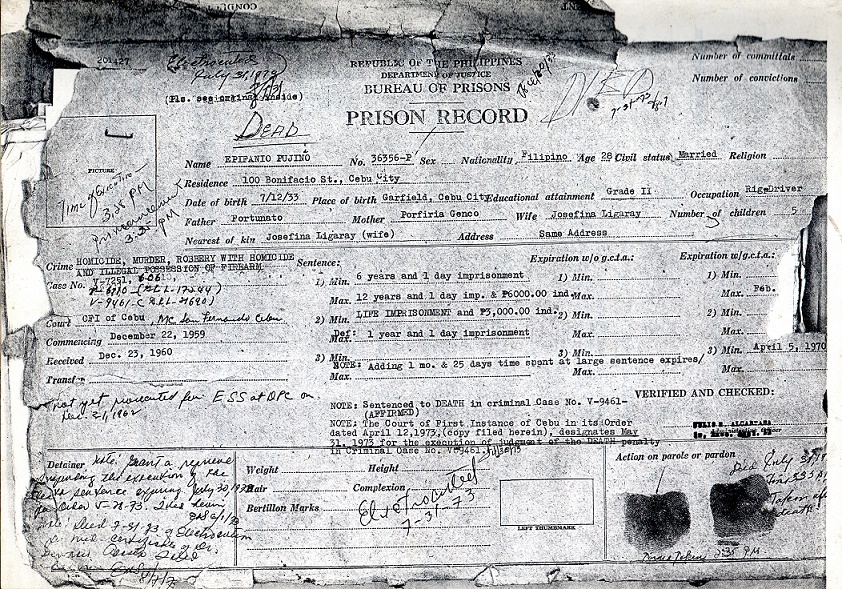

Then in 1923 came the electric chair. Mariano Jesus Cuenco, the author of Philippine Legislature Act (PLA) 3104 that changed the method of execution from hanging to electrocution, firmly believed that the electric chair will kill the convict instantaneously, unlike the excruciating death that hanging offered, which to him is “ignominious and barbaric.”

Then in 1923 came the electric chair. Mariano Jesus Cuenco, the author of Philippine Legislature Act (PLA) 3104 that changed the method of execution from hanging to electrocution, firmly believed that the electric chair will kill the convict instantaneously, unlike the excruciating death that hanging offered, which to him is “ignominious and barbaric.”

Cuenco’s legislation even bears this provision that eventually became Article 81 in the Revised Penal Code:

“The death sentence shall be executed with preference to any other and shall consist in putting the person under sentence to death by electrocution. The death sentence shall be executed under the authority of the Director of Prisons, endeavoring so far as possible to mitigate the sufferings of the person under sentence during electrocution as well as during the proceedings prior to the execution. If the person under sentence so desire, he shall be anaesthetized at the moment of the electrocution.”

Cuenco’s legislation even bears this provision that eventually became Article 81 in the Revised Penal Code:

“The death sentence shall be executed with preference to any other and shall consist in putting the person under sentence to death by electrocution. The death sentence shall be executed under the authority of the Director of Prisons, endeavoring so far as possible to mitigate the sufferings of the person under sentence during electrocution as well as during the proceedings prior to the execution. If the person under sentence so desire, he shall be anaesthetized at the moment of the electrocution.”

Of the 85 convicts that died in the electric chair, 17 requested to be anesthetized. Of equal number were those who refused any anesthesia.

Of the 85 convicts that died in the electric chair, 17 requested to be anesthetized. Of equal number were those who refused any anesthesia.

Some of them were advised by their priests to shun anesthesia for them to be clearheaded in their prayer in the last moments of their lives. The accounts or records of the other executions made no mention whether the convicts were given drugs to dull the pain of death.

Some of them were advised by their priests to shun anesthesia for them to be clearheaded in their prayer in the last moments of their lives. The accounts or records of the other executions made no mention whether the convicts were given drugs to dull the pain of death.

Death in the electric chair was, no doubt, painful and gruesome. The physician and the executioner would often coordinate to make sure that outward signs of pain were muted.

Death in the electric chair was, no doubt, painful and gruesome. The physician and the executioner would often coordinate to make sure that outward signs of pain were muted.

As retold by Dr. Ricardo V. de Vera, a physician who served at executions in the New Bilibid Prisons from 1959 until the ‘70s:

“Seeing everything is all set, I watch carefully the man strapped on the seat. His breathing is labored, and I can see very well the rising and falling of his chest as he respires. Inspire. Expire. Inspire. Expire. At the exact moment of expiration, I press the buzzer. A fraction of a second later two switches, one real and the other a dummy, simultaneously close permitting electric current to slam through the body of the doomed man. He shakes violently, the face and the body contort, his skin blackens, and an eerie sound emanates from the chair. But no sound comes from his lips because the lungs are devoid of air. After 3 minutes the current is switched off, and the body slumps with a thud.”

As retold by Dr. Ricardo V. de Vera, a physician who served at executions in the New Bilibid Prisons from 1959 until the ‘70s:

“Seeing everything is all set, I watch carefully the man strapped on the seat. His breathing is labored, and I can see very well the rising and falling of his chest as he respires. Inspire. Expire. Inspire. Expire. At the exact moment of expiration, I press the buzzer. A fraction of a second later two switches, one real and the other a dummy, simultaneously close permitting electric current to slam through the body of the doomed man. He shakes violently, the face and the body contort, his skin blackens, and an eerie sound emanates from the chair. But no sound comes from his lips because the lungs are devoid of air. After 3 minutes the current is switched off, and the body slumps with a thud.”

But there were botched executions. On April 28, 1950, Alejandro Carillo had to be electrocuted twice before he was declared dead; an electrical malfunction happened during the execution.

But there were botched executions. On April 28, 1950, Alejandro Carillo had to be electrocuted twice before he was declared dead; an electrical malfunction happened during the execution.

A number of convicts literally burned in the electric chair. The smell of burning flesh tested the endurance of the witnesses; more so when there were successive executions in a day. On December 28, 1951, a journalist passed out after witnessing three executions in a span of 22 minutes.

A number of convicts literally burned in the electric chair. The smell of burning flesh tested the endurance of the witnesses; more so when there were successive executions in a day. On December 28, 1951, a journalist passed out after witnessing three executions in a span of 22 minutes.

Emiterio Orzame Jr., however, showed extraordinary strength; when he was about to be executed on March 31, 1967, he ripped out the leather restraints and jumped out of the chair.

Emiterio Orzame Jr., however, showed extraordinary strength; when he was about to be executed on March 31, 1967, he ripped out the leather restraints and jumped out of the chair.

Dwight Conquergood, a scholar on how death penalty is performed, argued: “Botched executions knock down the ritual frame and expose the gruesome reality of actually putting a human being to death. The illusion of nonviolent decency is torn away. Botched executions also are the stuff of sensational news stories and political embarrassments. Graphic images and grisly reports of botched executions erode the public faith in the ‘ultimate oxymoron: a humane killing. To prevent embarrassing glitches and disruptions, modern executions have become ever more controlled, engineered, and bureaucratized performances.’”

Dwight Conquergood, a scholar on how death penalty is performed, argued: “Botched executions knock down the ritual frame and expose the gruesome reality of actually putting a human being to death. The illusion of nonviolent decency is torn away. Botched executions also are the stuff of sensational news stories and political embarrassments. Graphic images and grisly reports of botched executions erode the public faith in the ‘ultimate oxymoron: a humane killing. To prevent embarrassing glitches and disruptions, modern executions have become ever more controlled, engineered, and bureaucratized performances.’”

Lethal injection

At present, the use of lethal injection is the epitome of this kind of death work.

At present, the use of lethal injection is the epitome of this kind of death work.

The 1987 Constitution merely suspended the imposition of the death penalty by saying that “neither shall death penalty be imposed, unless, for compelling reasons involving heinous crimes, the Congress hereafter provides for it.”

The 1987 Constitution merely suspended the imposition of the death penalty by saying that “neither shall death penalty be imposed, unless, for compelling reasons involving heinous crimes, the Congress hereafter provides for it.”

And, in 1994, Congress did provide for the reimposition of the death penalty for certain heinous crimes by virtue of Republic Act (RA) 7659. The preferred method of execution in RA 7659 is the gas chamber.

And, in 1994, Congress did provide for the reimposition of the death penalty for certain heinous crimes by virtue of Republic Act (RA) 7659. The preferred method of execution in RA 7659 is the gas chamber.

But two years after the law took effect, the government was not able to build one. Going back to the electric chair was out of the question. Besides its documented cruelty, the execution chamber housing it was, in a rare display of poetic justice, hit by lightning and burned down on July 8, 1986.

But two years after the law took effect, the government was not able to build one. Going back to the electric chair was out of the question. Besides its documented cruelty, the execution chamber housing it was, in a rare display of poetic justice, hit by lightning and burned down on July 8, 1986.

In 1996, RA 8177 amended both RA 7659 and Article 81 of the Revised Penal Code; it provided for lethal injection as the means of execution. Seven convicts were killed via lethal injection from February 5, 1999 until January 4, 2000.

In 1996, RA 8177 amended both RA 7659 and Article 81 of the Revised Penal Code; it provided for lethal injection as the means of execution. Seven convicts were killed via lethal injection from February 5, 1999 until January 4, 2000.

Then on June 24, 2006, Congress passed RA 9346, effectively abolishing the death penalty.

Then on June 24, 2006, Congress passed RA 9346, effectively abolishing the death penalty.

In the 76 years spanning the first execution in the electric chair on June 25, 1924 until the last execution via lethal injection, the state had claimed 92 lives. Their executions should have been object lessons promoting fear and docile citizenship.

In the 76 years spanning the first execution in the electric chair on June 25, 1924 until the last execution via lethal injection, the state had claimed 92 lives. Their executions should have been object lessons promoting fear and docile citizenship.

But the state was caught in a bind. It can get rid of monsters but it cannot be perceived as imposing the death penalty in a monstrous manner. This provided the convicts with ways to reassert their humanity.

But the state was caught in a bind. It can get rid of monsters but it cannot be perceived as imposing the death penalty in a monstrous manner. This provided the convicts with ways to reassert their humanity.

Marcial “Baby” Ama, upon his execution on October 4, 1961, donated whatever was left of his earthly belongings to the Home for the Aged and Infirm. In the 1960s, several executed convicts donated their eyes for those needing transplant. Casimiro Bersamin, a Bataan veteran and a convicted murderer, asked that he be shown the Philippine flag as his last wish during his execution on July 21, 1951. Leo Echegaray, convicted child rapist, had a wedding on December 28, 1998; he was the first to be executed by lethal injection on February 5, 1999. Others simply walked to their death with all the calm and dignity that they could muster.

Marcial “Baby” Ama, upon his execution on October 4, 1961, donated whatever was left of his earthly belongings to the Home for the Aged and Infirm. In the 1960s, several executed convicts donated their eyes for those needing transplant. Casimiro Bersamin, a Bataan veteran and a convicted murderer, asked that he be shown the Philippine flag as his last wish during his execution on July 21, 1951. Leo Echegaray, convicted child rapist, had a wedding on December 28, 1998; he was the first to be executed by lethal injection on February 5, 1999. Others simply walked to their death with all the calm and dignity that they could muster.

It is the height of irony for the public to learn not contempt and terror, but a lesson in human dignity offered by a criminal condemned to death. Instead of witnessing the end of monstrosity of a criminal life, the public sees the monstrosity of its government.

It is the height of irony for the public to learn not contempt and terror, but a lesson in human dignity offered by a criminal condemned to death. Instead of witnessing the end of monstrosity of a criminal life, the public sees the monstrosity of its government.

A look at the history of the killing of convicts in the Philippines yields the lesson that a state relying on murder as a tool to impose its authority is weak and insecure, and unremoved from the very barbarity it would like to extirpate.

A look at the history of the killing of convicts in the Philippines yields the lesson that a state relying on murder as a tool to impose its authority is weak and insecure, and unremoved from the very barbarity it would like to extirpate.

The monstrosity of the criminal will be just a mirror image of the monstrosity of the state.

The monstrosity of the criminal will be just a mirror image of the monstrosity of the state.

As Polish sociologist and philosopher Zygmunt Bauman argued, the “audacious dream of killing death”—the act of preserving society from the “dangerous classes”—turns into the practice of killing people."

As Polish sociologist and philosopher Zygmunt Bauman argued, the “audacious dream of killing death”—the act of preserving society from the “dangerous classes”—turns into the practice of killing people."

Aren’t we already doing that?

Aren’t we already doing that?

(Joel F. Ariate Jr. is a university researcher at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. VERA Files is put out by veteran journalists taking a deeper look at current issues. Vera is Latin for “true.”)

(Joel F. Ariate Jr. is a university researcher at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. VERA Files is put out by veteran journalists taking a deeper look at current issues. Vera is Latin for “true.”)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT