For three decades or so, Armand Mijares has been climbing mountains and exploring caves, initially as an anthropologist studying the culture of indigenous groups, and later as an archaeologist searching for clues about the past.

With the success of his latest discovery, one can consider him the Philippines’ very own Indiana Jones –minus the death-defying stunts and golden treasures.

He even has the classic Indiana Jones theme song as a ring tone to boot.

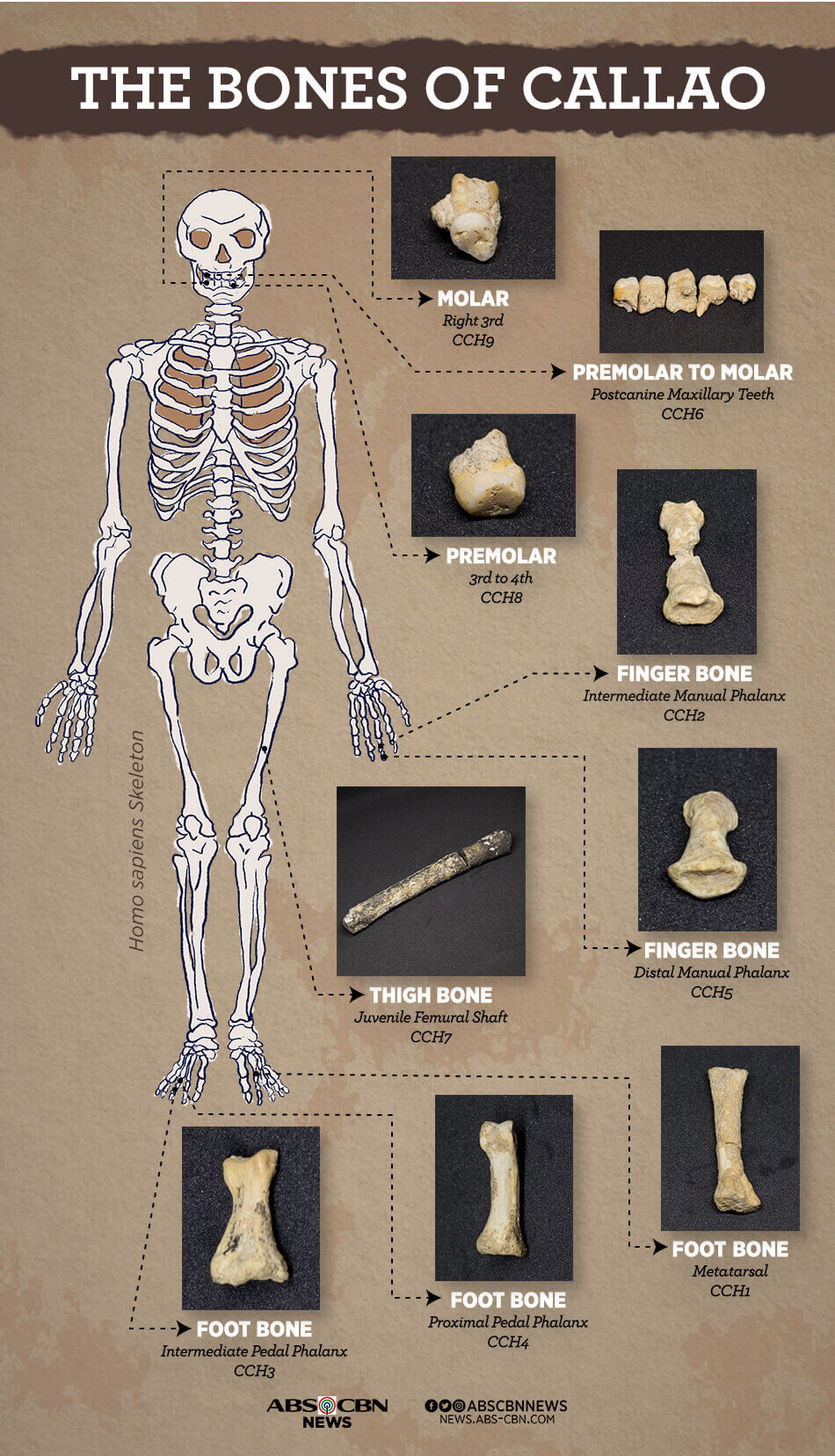

Inside his office at the University of the Philippines (UP) are hundreds of knick knacks and curiosities, including two replicas of hominid skulls and a conspicuous yellow briefcase. Locked inside that briefcase are his latest treasures – 13 teeth and bones from a new species of ancient humans.

Mijares and his colleagues from around the world concluded that the fossilized remains make up an never-before-seen hominin species, which they now call Homo luzonensis based on the Philippines’ largest island Luzon.

“The discovery situates the Philippines as a major area of human evolutionary research,” Mijares said during a press conference last April 11 when he announced the findings.

He also believes that the discovery will result in many Philippine textbooks being revised to include theHomo luzonensis, not only as a new species, but as the oldest known ancient human in the archipelago.

Game-changing

As an archaeologist, Mijares always believed that only Homo sapiens – the species of the modern man – had been present in the Philippines, especially since most of the country was not connected to mainland Asia at a time when ancient humans were migrating out of Africa.

But when in 2007 he found a foot bone that did not fit in the description of Homo sapiens and other ancient human species, he started questioning his own beliefs.

“I needed to shift my own paradigm. I was on the side then…I was a believer that only Homo sapiens arrived in Luzon,” he said.

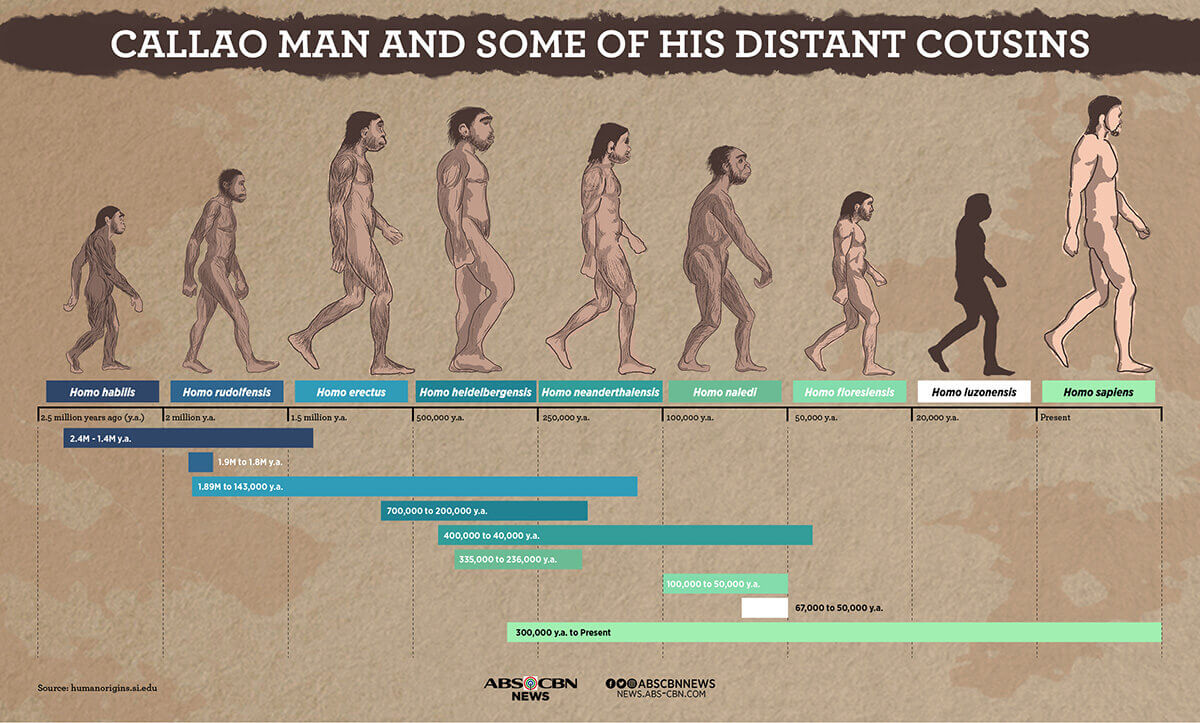

Mijares explained that before he found Homo luzonensis, there were only three species from the human family tree that was proven to have existed in Southeast Asia – the modern man Homo sapiens, the 2-million-year-old Homo erectus, and the “dwarf” Homo floresiensis, dubbed “The Hobbit.”

For a while, the oldest fossilized remains in the Philippines were that of the “Tabon Man” from a cave in Palawan. “Tabon Man” was later classified as Homo sapiens. At least 67,000 years old, Homo luzonensis is now the oldest archaic human that existed in the area that is now known as the Philippines.

Callao Cave

Mijares found the curious foot bone in Callao Cave, in a town in Cagayan province, around 500 kilometers north of Manila.

The town of Peñablanca, bordered on the east by the great Sierra Madre mountain range, is home to 300 caves and 118,000 hectares of protected forest land.

Of these, the 7-chamber Callao Cave is the most popular. At one point, locals converted one of its chambers into a chapel, now called the “Divine room.”

But unknown to tourists, Callao Cave has tens of thousands of years’ worth of history just waiting to be uncovered.

Callao Cave has been the subject of excavations of the National Museum as early as 1979. Mijares himself excavated it in 2003 as part of his dissertation for his Ph.D. But they have never dug deeper than the usual two meters. And the only instance the National Museum reached 7.5 meters, nothing of significance appeared.

Mijares said he was inspired to return to Callao Cave after a team of archeologists in Indonesia uncovered fossilized remains of a new species called Homo floresiensis. Dubbed the “Hobbit,” Homo floresiensis has been described as having a small body and possibly evolved from Homo erectus.

In 2007, Mijares dug deeper and away from the original trenches that the National Museum initially dug in the western side of the cave’s antechamber.

Years of experience of surveying caves and studying their soil also allowed Mijares to identify areas in the eastern side of the cave that might have more fossils.

“Since I’ve been digging a number of trenches I know the substructures and how all the stones are forming. I know where the water would flow and where to be able to concentrate,” he said, explaining how water would carry smaller fossils into different parts of a cave.

Digging Season

So, for six weeks, every other year starting 2007, Mijares and his team set camp in living quarters near Callao Cave. Every day, they rode a boat to cross the river and climbed almost 200 steps into the tourist cave.

Mijares called this his only “vacation” from academic work.

“If you have a good group, a good team, then there’s fun in it,” he said. “After the dig, after you swim across the river, you have a couple of beers at night. You’re discussing things.”

Of course, it’s not all fun. For 8 hours a day, they sit inside the trenches and “dig” by scratching the surface with sticks and brushes, making sure that whatever lies underneath won’t be damaged.

While 2007 was his breakthrough year with the discovery of the foot bone, 2009 was his worst. He found nothing after following the advice of his colleagues. But despite depression setting in, he said, “It strengthened my determination to excavate.”

“In 2011, I followed my gut,” he said, explaining that he returned to the eastern side of the cave to dig.

“The fear of getting zero fossil again was hitting me. You get depressed but you persevere, you continue,” Mijares said.

One day, tired and frustrated at the outcome of the dig, one of his team members started playing songs from the band “The Beach Boys.”

“We’re singing the Beach Boys and we start excavating and then fossils start to come out. One at a time. The next day, we’re excavating. None again. We play the Beach Boys. Then fossils come out,” Mijares said.

“2011 was the luckiest year. When we got most of the fossils.”

That year, his team found a thigh bone, two toe bones, two finger bones and six teeth.

To solidify their claim of a new species, Mijares returned to the cave in 2015. That was when they found the last molar, which satisfied the requirement of having fossilized remains from three individuals.

But it would take a couple or more years of analysis to be sure about their findings, publish it and finally announce it to the world.

Initially, they used uranium-series dating, which uses radioactive material, to determine the age of the bone. Then Florent Detroit, Mijares’ colleague from France, used advanced technology called geometric morphometrics, which basically creates a virtual or 3D digital copy of a specimen or a fossil to compare it with virtual copies of other species.

Growing family tree

There are about a dozen or so species of archaic humans. Some of them lived as contemporaries while others evolved into new branches of the family tree.

Mijares said it is still impossible to determine how the Homo luzonensis fits into this tree, especially with its mosaic features.

“It’s still hanging. To connect it, to link it to a family tree is a bit difficult if you only base it on morphology,” he said of the fossils’ physical features. “It has Australopithecus features, it has Homo erectus features and it has Homo sapiens features. So where would it align? We don’t know.”

What is clear to him though, is that it is a new species.

“It’s just boxes,” Mijares said, referring to the identification of new species. “You have Homo sapiens. You have Homo erectus. You have Neanderthals. If you fit the box and then you go to one box. But if you don’t, where do you go? Then you create a new box. That’s basically how you do your typology.”

Crossing the Sea

Based on uranium series-dating, Homo luzonensis was at least 67,000 years old. This means it lived during the Old Stone Age when archaic humans were using tools to hunt for food and for other activities.

It is still unknown how they reached Luzon but Mijares disagrees with those who claim that a tsunami or a similar natural phenomenon brought them to the archipelago.

“But the problem with that is we know when tsunami hit Aceh in Indonesia and in Japan. People die. Probably one or two survive floating somewhere in the sea. But you need a good-sized population to procreate and establish a community,” he said.

Instead, Mijares believes that the Homo luzonensis were just as crafty as modern people.

“There might be some other forms of vessels created by other species,” he said, pointing out that even ancient human species had opposable thumbs, giving them the ability to grasp things like tools.

“You can tie things. You only need 3 or 4 logs or bamboo, tie them up, you have a raft. You can cross. Maybe you cannot fully control it but somehow that thing will float and bring you somewhere. With the proper current or proper wind, it can bring you to Luzon,” Mijares said.

Unfortunately, they have yet to find tools in the dig site in Callao Cave although cut marks on animal bones found there suggest the possibility.

Dwarves

Mijares thinks that the species “shrank” as they adapted or evolved living in an isolated island with limited resources. This makes Homo luzonensis the second dwarf species of ancient humans after Homo floresiensis was found in the island of Flores in Indonesia in 2003.

Estimated to be less than four feet tall, an adult Homo luzonensis might have been shorter than a 6-year-old child.

While it is impossible to imagine how it would have looked like, without the discovery of a skull and larger bones, Mijares pointed out certain features that make it interesting.

One peculiar feature of the species is its curved foot bone, similar to that of ancient hominids from the Australopithecus genus.

But Mijares believes that despite the curved foot bone, Homo luzonensis was bipedal, one of the reasons why it is classified under the genus Homo.

“The environment can be a semi-closed, semi-forest system that may require more climbing than walking. Or they will require climbing to get some food. But definitely they are bipedal. They are walking on the ground,” he explained.

In general, the Homo luzonensis’ teeth were smaller compared to other species. The premolars also had two or three roots like primitive species such as Homo erectus. These were also bigger in relation to the molars, which is not the case among modern humans.

Debate

Some scientists have questioned the finding, wanting more evidence such as a skull bone or DNA.

But as Mijares and other experts have pointed out, fossilized remains in tropical areas like the Philippines are unable to retain DNA because of humidity.

“Well, what’s enough? How can you say what’s enough?” Mijares said.

He explained that the Denisovan species, another extinct species of archaic humans that interbred with ancestors of modern humans, was determined based only on one molar and one end of a hand bone. However, it had a lot of DNA since it was preserved in cold climate.

“Homo floresiensis (is) almost complete and yet they’re still debating what it is. It’s not the amount of number (of fossils) that is required. It’s the ability to provide information that there is a distinct characteristic for this set of bones. And based on our experience and what we presented to Nature and the scientists who assess us, it is a new species,” Mijares said.

He believes that the debate will continue, as was the case with other discovered species.

“We need more data, we need more discoveries. It might even take another generation to be able to really say what it is,” he said.

Island Evolution

Mijares said the discovery of Homo luzonensis is important in understanding how evolution worked in islands.

“It complicates now our view of human evolution. It situates the islands as a particular laboratory for natural selection,” he said.

On the other hand, Mijares said modern humans could learn something about how ancient species went extinct.

“They (Homo luzonensis) were able to adapt until they died out. There is a time and point in history, in our environment where their physicality, their make-up can no longer let them survive. So they died out. That’s for us also to think of. Our species, Homo sapiens…there might be in the future a specific environment wherein our species would die out if we don’t evolve.”

With some experts questioning the discovery of the Homo luzonensis, Mijares plans to answer one question at a time, hoping that he will be able to find more evidence that would shed light into the appearance and behavior of the dwarf species. He is also hoping to show to the world that Filipinos can do world-class research despite having less funding and resources – just like how Homo luzonensis adapted to become resilient.

Meanwhile, like Indiana Jones, Mijares is off to another adventure soon, hoping to unearth more priceless treasures – not made of glittering gold but of fossils that tell the rich history of the human family.