"A cause greater than myself"

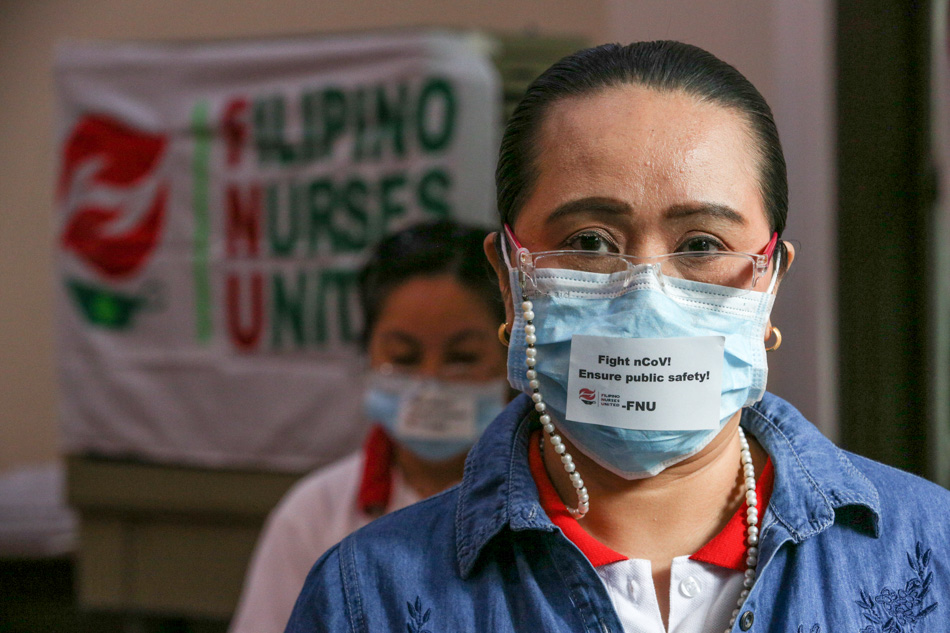

They call it a war against an unseen and unpredictable enemy: the new coronavirus. What is not invisible are Filipino health workers in the frontlines during this global pandemic – exhausted, frustrated, terrified and dying.

Even so, they remain dedicated to saving lives. These are their stories.

The emergency-room doctor

It usually takes three cups of coffee, white mocha Americano – piping hot with two pumps of syrup – before she can start her work day.

These days, however, caffeine is of no use to Catherine. Days can’t begin when they don’t really end.

Since March 16, she has had trouble remembering dates. Work hasn’t stopped – save for a few hours of stolen shut-eye in empty rooms. Days and hours have bled into each other.

“I don’t even know anymore. That’s how long I’ve been living here,” she says.

Catherine, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, is an emergency physician in one of the biggest private hospitals in Metro Manila.

Since the new coronavirus reached the Philippines, the hospital’s emergency room (ER) has been filled to the rafters. Doors have swung almost non-stop, gurneys roll in all directions, and nurses’ stations are swamped with patients suspected to have been infected by the virus.

“Our hospital is full. And we cannot turn down patients. Ambulances come, they just dump patients or they just leave patients here at our ER,” she explains.

During her last shift alone, there were 11 critical patients rushed to the ER. Five of them were intubated because of respiratory distress – one of the potentially fatal symptoms of COVID-19 or the coronavirus disease.

The patients aren’t going anywhere. ERs aren’t meant to be intensive care units (ICU) or even recovery rooms. But the lack of available space in the hospital has forced the ER to morph into what Catherine describes as “an animal of its own.”

“Ang dami naming naiiwan na patients sa ER ngayon kasi the hospitals are full. When we call district hospitals, nobody accepts us anymore. Because they will say they're also full,” she says.

“The fear now is that the ER is inundated with cases na kami na ‘yong magiging ICU. Na hindi trained ang tao. I am not even trained in ICU care. So we're scared for that point na kami ang magha-handle ng everyone admitted and non-admitted.”

The ER has been split into two sections: non-COVID cases and another one for those with respiratory cases. The split meant even more work for the already limited manpower in the ER while resources continue to dwindle.

“You know, when we go on duty now, para kaming mga nababaliw na kasi instead of us saying something like iyong usual namin, ‘Oh, ika ilang duty mo na?’ Ganyan. Ngayon, hindi na. ‘Ilang araw ka nang nakatira dito sa ospital?’ Ganoon na.”

“You see, previously we can handle 500 patients in 24 hours. But those patients, we were able to discharge, we were able to admit to the ICU or to the room. Ngayon wala ng room. Nandoon na lang sila sa ER. Naiipon nang naiipon.”

Exhaustion has taken on a new meaning for Catherine and her team. Yet the long hours and the stress of managing a crowded emergency room are nothing compared to the fear of exposure to the same disease they are trying to extinguish. And that fear becomes more tangible as days go by.

On March 21, three doctors from other hospitals in the metro were confirmed to have died from the coronavirus disease.

“Kahit naka-full personal protective equipment (PPE) ka naman, if you have so many patients, you're bound to get it eventually. Sa pagod mo, kung minsan hindi mo alam kung naalis mo ba nang tama 'yung gown. Hindi mo na sure kung tama ba 'yung paghugas ko, nakahugas ba ako ng kamay bago ko hinawakan 'yung mata ko? Bago ako kumain? Bago ako uminom ng tubig?” she says.

“‘Yong kinakatakot ko ngayon na sa sobrang pagod na, makakalimutan na namin ‘yong tama."

While Catherine is concerned about her own safety, she also worries about the rest of her team -- nurses, medical technicians and administrative clerks. And then there are the security guards who are the first to welcome incoming patients and cleaners who keep the hospital, well, hospitable.

Because while the virus is dangerous, what could kill health workers are the lies patients tell them. Some patients have deceived Catherine and her team, refusing to disclose medical and travel history at a time when the simple truth can be the best protection for both patient and health care worker.

“A lot of the patients lie and this has been happening since a long time ago. Kahit na wala ‘yong COVID, nagsisinungaling na talaga and I don't know why. Sometimes, I think it is the culture.

"They won't say the truth. And then later on, kapag nag-probe nang nag-probe ang doctors, doon lang sila aamin,” she says.

There are never really good days inside emergency rooms. But in the time of coronavirus, there are just bad days and even worse days with no end in sight. Groundhog days full of circles and loops and never a period for relief.

“We’re very much in despair. Sometimes, we'd just start crying but then let's work again. Everyday we pray that this stops soon. We don’t know what to do anymore. Kasi parang palala na siya nang palala,” she says.

For Catherine, there are moments when she just wants to quit and leave. Yet the sight of her team – working relentlessly in spite of the danger – makes her stay.

“I have one cleaner, siya lang. Siya na lang. Para siyang nakatira na lang dito sa hospital kasi wala na 'yung iba nilang cleaners, ayaw na din pumasok. Pero nakikita niya kasi na kailangan din namin siya so she still comes,” she says.

“I have to show them that I'm one with them because if they see that I'm not coming anymore, they are not going to come also. I cannot abandon them. Kami-kami na lang 'yung magtutulungan.”

Catherine longs for a now distant past when she would have three cups of coffee before work begins. Nowadays, she barely has any sleep yet she’s still working.

Wide-awake but it still feels like a nightmare.

“I think all of us are scared pero you have to put that aside kasi if we are all scared, we can't do our job and we know na kailangan pa rin kami. Because at the end of the day, iniisip namin, paano kung kamag-anak ko itong pasyente? Sinong mag-aalaga kung aalis kami sa frontlines. If not us, then who?”

The Nurse

Every March 13 for the past 8 years, Emily and her family would gather in their home in Nueva Ecija to celebrate her late father’s birthday -- a simple gathering of loved ones over noodles, sweets and a birthday cake.

It’s a promise she made by her father’s bedside before she lost him to a heart attack in 2011. A promise she has kept since – except this year.

Ever since the coronavirus disease pandemic broke out a few weeks ago, she made a deliberate decision to stay away.

Emily works as a nurse in one of the leading private hospitals in Metro Manila, where more than a dozen patients have tested positive for the contagious disease. (She has requested to conceal her real name and the hospital where she works.)

Her work exposes her every day to the risk of contracting the virus. And the thought that she could carry it with her when she goes home is simply too much to bear.

“Usually ito naman 'yung fear naming lahat ng nasa hospital, na pagdating ng bahay, madala namin ‘yong virus sa family namin na hindi namin alam na kami 'yung carrier. ‘Yon iyong nakakatakot,” she says.

“Parang ‘yon na lang ‘yong lagi mong pinagpi-pray na sana wala kang dala. Na ginawa mo naman lahat para makatulong sa iba, du'n sa mga PUIs (persons under investigation) and positive, na sana pag-uwi mo, wala kahit ano kang madala na virus or what sa family mo.”

Emily is not new to her line of work. She has spent 8 years in the same hospital but nothing prepared her and her colleagues for the rise of the new disease.

“At first, siyempre, nagkaroon ng panic. Siyempre 'yung fear nandu'n kasi first time mong makahawak including persons under investigation,” she shares.

Soon after the Department of Health confirmed her hospital’s first positive COVID-19 case, the staff who handled the patient went into self-quarantine. Those who felt they had symptoms – cough, colds, backpain, diarrhea – had themselves checked at the emergency room and admitted to the hospital. They were tested and all of them were cleared.

A few weeks later, things returned to normal -- or at least, what is considered normal during these times.

“So ngayon parang at peace kami kasi pagdating sa amin, naka-PPE (personal protective equipment) kami, naka-ready kami. After the procedure, linis agad ng room, pa-disinfect agad. So ‘yong protocol, nasusunod naman,” she explains.

But Emily is less worried about herself.

“Ako kasi, mas worried ako sa family ko . . . Alam ko paano i-manage sarili ko. Nasa hospital ako, any time puwede ako magpa-ER. Paano sila?”

Since her last visit to Nueva Ecija on March 5, the calls, video calls and chats with her family have only become more frequent.

“Tumatawag ako thrice a day para i-remind sila kung sino lumabas, kung ano ginagawa nila, kung sino nakasama nila this day, kung sino pumunta sa bahay na relatives. Sinasabihan ko sila na as much as possible, huwag muna pumunta kung saan-saan. Every day ‘yong pagpapaalala,” she says.

Her concern grew upon learning that Metro Manila has been placed under community quarantine with the ensuing mad rush of passengers heading home to their provinces before the government suspended travel to and from the nation’s capital region.

“‘Yong worry ko kasi, baka may biglang nakasalamuha ng parents ko or kung sino man sa family ko na nasa province tapos madala nila sa bahay. ‘Yon ang ayoko mangyari," she says.

"Ako pinili ko talaga na di umuwi ilang weeks na for them tapos malalaman mo ibang tao nagdala sa kanila, ibang tao 'yung nakaano sa kanila and then biglang sila magiging carrier and then mapapahamak family mo. ‘Yon ‘yong greatest fear ko talaga.

“Di rin ako makakauwi, paano sila? Nag-aalaga ka ng ibang taong may sakit tapos 'yung family mo, hindi mo mauuwian.”

Her concern is not unwarranted. She says some hospitals in her province turn away patients with fever, cough and colds without even assessing them, referring them instead to larger tertiary hospitals a few kilometers away who can offer specialized medical services.

A patient in Nueva Ecija also recently tested positive.

Emily knows all too well the challenge every COVID-19 patient faces.

“Ang hirap. Kasi once na nag-positive ka, bawal lahat. Walang dalaw, ikaw lang mag-isa sa room. Ang makaka-interact mo lang is 'yung primary doctor mo, tsaka ‘yung nurse mo, kung sino nurse mo for the day. Bawal dalaw, bawal kahit sino,” she shares.

“May fear ka na hihintayin mo results mo tapos mag-isa ka, wala kang kausap. ‘Yon ang sabi nila and ‘yon din mararamdaman ko if ever ako nandu'n sa room. ‘Yong stress level mo, sobrang tataas talaga.”

No medicine has been approved, so far, for the disease and a vaccine is still in the works.

And there’s no telling when the COVID-19 crisis in the Philippines will reach its peak and how much longer it’ll stay.

It’s a brutal time for nurses across the country. Not that it wasn’t before.

For all the work they do and the hazards they face, nurses in the country only earn around P20,000 monthly on average -- even lower for some private hospitals in the provinces. In the United States, the average monthly salary of a nurse is equivalent to P200,000.

The COVID-19 crisis may have added more hours but the pay hasn’t changed. It hasn’t stopped them, however.

Emily says she knows of other nurses who walk for hours just so they can get to work. Even without public transportation or their own private vehicles, nurses find a way back into their scrubs.

For all her resolve to stay and work, Emily acknowledges there are moments when she prays that she can’t help but shed a tear for both her colleagues and patients.

“Every day, I check the data. Kung ilan na ‘yong positive na admitted sa hospital namin. Every day, it is increasing. Sobrang sakit sa dibdib knowing na mas dumarami pa instead of nababawasan,” she says.

“Sobrang takot na ang lahat. ‘Yong feeling na kung puwede lang na hindi ka na pumasok just to save yourself pero hindi puwede. Kasi you are under oath and hindi makakayanan ng konsensiya mo na iwanan lang bigla-bigla ‘yong mga kasama mo habang nakikipaglaban. Sobrang nakaka-depress. Pero iisipin mo pa rin kalagayan nu'ng mga taong hindi mo naman kilala pero pinagsisilbihan mo para mabuhay para sa pamilya nila.”

These days, Emily’s phone serves as her lifeline. She places it inside a zipper-storage bag or cling film while on duty, carefully washing her hands and unwrapping it after.

Aside from calling her family or checking her chat messages, she scrolls through their photos she has managed to keep all these years.

“Lagi, 'pag umuuwi, lagi kami may family photos. Simula nang mawala dad ko, as much as possible, kahit once a month, uuwi kami to visit mommy namin,” she said.

“Iniisip ko na lang din, working ako abroad na di ko sila makikita for ilang months lang.”

Emily longs for the day when all of this will be over, when she could go home whenever she wants to and enjoy her mother’s halabos na alimasag. A serving of steamed crabs, a taste of home and a smack of normalcy.

She took care of her father when he was bed-ridden, a little more than a year before he died. She wants to be there too, for the rest of the family.

But for now, the only way to keep them safe is to stay away.

The nephrologist

Look, up in the sky! It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s Superman!

Dr. Frederick Verano is a fan of the Man of Steel. Growing up in the 80s, he went on vicarious adventures through afternoon animation with the DC superhero: solving crime, defeating the bad guys and saving lives.

A hero in times of crisis. Someone you can depend on. That was his childhood fascination.

These days, Frederick is living the dream. Most recently, many have actually called him a hero. He is one of thousands of frontline medical workers battling a nefarious new villain: the coronavirus.

Yet Frederick will be the first to admit that he’s no Superman. He has no special powers, unless his expertise as a kidney specialist counts. For him, it’s just about doing his job and making good on his word – even as fear hangs heavily in the air.

“Mayroon kaming oath na sinumpaan, 'di ba? Sa kahit anong sitwasyon, siyempre buhay ng pasyente pa rin na nangangailangan ng tulong namin. Iyon ang priority namin. Nakakatakot talaga pero wala naman kaming ibang choice kung hindi maging matapang para sa pasyente namin.”

Yet the kid in Frederick still finds a certain sense of anticipation when his daily “costume” comes on: respirator masks, gloves, surgical gowns and eye gear. His colleagues are all wearing the same personal protective equipment or PPE.

“Para kaming Super Friends,” he says.

They would often take the time to take a photo of the team – in hero poses – to document how strange these times are.

“Fighting form namin ‘yon. Pang-motivate namin sa isa't isa na lalaban kami,” he says.

In the hospital where Frederick works, there’s a ward devoted to confirmed and suspected COVID-19 patients on almost every floor. A ward accommodates 15 patients each.

Frederick is assigned one floor.

The sheer volume of patients has forced many doctors such as Frederick to temporarily step back from their specialties and instead serve as general internists.

For six hours – sometimes more – Frederick has to do his patient rounds wearing the PPE.

With high risk of exposure to the virus, this is their armor, their only line of defense against the hazard.

“‘Yong nakakakaba lang ay sa loob ng isang linggo, pinakiramdaman ko parati 'yung sarili ko kung magkakaroon ako ng sintomas o wala. I think isa ‘yon sa pinakamahirap,” he says.

It doesn’t help that some patients either lie or refuse to disclose important, live-saving information.

In one case, Frederick was called in to check on an elderly patient who had respiratory distress. He had his suspicion that the case was COVID-related, yet the patient wasn’t upfront about his travel history.

A few days later, test results proved that the patient was indeed infected by coronavirus.

“Noong nalaman ko iyon, para akong binuhusan ng malamig na tubig sa katawan ko. Pinagpapasalamat ko na lang na, though hindi complete iyong PPE na suot ko, naka-N95 mask ako saka naka-gloves ako that time,” he recounts.

“Pasyente sila, doktor kami. Kapag nagpunta naman sila sa ospital, wala naman kaming ibang puwedeng gawin kung hindi tulungan sila. Honesty lang hinihingi namin para maibibigay namin nang tama iyong treatment para sa kanila.”

Frederick considers himself and his team “lucky” when it comes to having enough supply of PPE. Not all hospitals in the metro have that “luxury” – a strange description for something that should be a basic requirement.

On social media, health workers have posted photos of creative ways they have dealt with the lack of equipment. Instead of masks, some are wearing face shields meant for industrial work. Others have plastic bags over their heads, with holes punctured for their eyes. There are some with black trash bags on instead of surgical gowns.

Frederick knows how severely limited PPEs are in hospitals these days, which is why he maximizes each chance he gets to suit up.

“Nakasuot sa ’yo ‘yong PPE mo na napakainit, alam mo 'yun? Ang hirap makahinga. Na hindi ka maka-CR. Hindi ka maka-break. Gusto mo na kumain pero sasabihin mo sayang 'yung PPE mo kasi nagkakaubusan. ‘Yong konti iyong supply. Kapag hinubad mo, gagamit ka ulit ng bagong PPE,” he says.

Aside from the PPE, Frederick also has to wear many other hats in his job. One of them is being a counselor.

Because of the highly infectious nature of the virus, patients are placed in isolation for at least 14 days. Health workers are their only human, physical contact during that time.

“Isolated sila. Wala silang nakikitang kamag-anak. Nakakulong sila sa kuwarto . . . Sa cellphone lang nila nakakausap pamilya nila, bawal ang bantay sa kanila, wala silang nakikita, di ba? Pumapasok 'yung depression sa kanila. Hindi nila nakikita 'yung mga loved ones nila. 'Yung costs ng hospitalization din. Kasi nga biglaan di ba? Hindi sila handa,” he says.

“Kino-console namin sila. We join them in prayer. We tell them to always look on the positive side of things. Kung mayroon man. Behind the mask, kailangan iparamdam namin na naka-smile kami para sa kanila.”

He says it’s difficult to smile these days. It amost feels criminal to do so at a time when there’s so much grief and mourning happening.

But for Frederick, it’s important to remain hopeful even if it’s difficult. Happiness, he says, could be contagious, too.

“Kung hindi pa ako magiging happy, kawawa naman iyong mga taong nakapaligid sa akin,” he says.

At a time when optimism is scarce, the strength to dig deep is a feat of its own.

Maybe that’s his superpower.

The chief

Francisco Duque III isn’t from the military, but he carries himself like a soldier.

He lives for rules and follows a routine so rigid that for others, it comes off as almost robotic.

No one sees the 63-year-old health secretary slouch. His posture is always on point -- chest out, shoulders straight, mechanical and calculated movements.

Without fail, at exactly five o’clock in the morning on weekdays, Duque is already in his uniform: a short-sleeved office barong.

He has very specific preferences. Visit his office in Manila and you’ll be greeted with a warning in big bold letters: No perfume and strong fragrances please. The secretary has a thing for pungent scents.

Duque would rather have a dim room. He doesn’t like bright lights.

But recent weeks have forced the secretary out of his comfort zone. His world has completely been upended by the coronavirus pandemic.

He’s no longer in his barong. Instead, a plain shirt and walking shorts. He’s out of the office. Far from his desk with the neatly piled documents and the sign at his door.

After a colleague at the health department tested positive for the coronavirus, the good doctor was forced to stay home for quarantine.

In the past few weeks, Duque has been seen and heard all over the media; first confirming that the dreaded new coronavirus has indeed made its way to the Philippines. And then assuring the public that they are working hard to prevent it from spreading further.

But just as the public was already anticipating the numbers to surge, several weeks passed when the Department of Health, brimming with pride, reported no new cases.

Still, they encouraged the public to undergo self-quarantine especially if they have been outside the country.

The new coronavirus does not respect borders. It does not recognize social status.

Duque’s closest encounter with the virus was a foot away, during a meeting attended by one of the department’s directors. And the first high-ranking health official to test positive for COVID-19.

It never crossed his mind that he would need to place himself under the same safety procedure.

Duque belongs to the vulnerable population: senior citizens with pre-existing health conditions.

But as health chief, he knows he can’t show weakness. He’s not allowed to show fear.

“Of course, there was a bit of concern because I am a person with medical problems like asthma and hypertension. But that’s about it. I just thought I needed to do what I needed to do, which was to seek the advice of my team at the DOH,” he says.

There is nothing easy about being placed under quarantine. Many Filipinos know this all too well by now. Now, so does the secretary.

“It’s difficult because you have to isolate yourself. You isolate yourself from your family members. They have to be strict observers of physical distancing. It’s so difficult. But I have to practice what I preach. We have to walk the talk so to speak. I get to see my wife, pero naka-mask kami pareho. Mayroong distancing,” he says.

At a time when the entire country is fighting a deadly virus, a public servant’s last thoughts should really be about himself.

Four days into quarantine and with small bouts of cough, Duque says that learning of the dire conditions of his “soldiers” at the frontlines is a bitter pill to swallow.

Social media has erupted with clamors to aid tired and ailing healthcare workers.

Many of them face their own battles. But they choose to do what they do.

Amid the scorching heat, they endure walks that stretch kilometers. They carry the pressure to keep their hospitals up and running, even if this means their own households may be put on hold.

At home, in his bedroom, Duque continues to monitor the worsening situation.

“There is a lot I need to orchestrate. The arrival of the test kits, the Bureau of Customs releases these immediately because of the FDA [Food and Drug Administration]. Clearance is here. It even comes to a point that I have to personally ensure that the cold chain of these enzymes are delivered from the RITM [Research Institute for Tropical Medicine] to the different laboratories,” he says.

Like a general to his lieutenants, Duque is determined to guide them towards victory.

His only problem: no one ever anticipated the virus to be this infectious.

As the days progress, his soldiers become more and more ill-equipped in the medical battlefield.

“Who doesn’t want to provide a complete set of PPEs? We are trying our best to really get us many PPEs as we could possibly get. But all the manufacturing companies did not expect this,” he says.

“Our procurement will only start to come in by April 3. At hindi pa nga ‘yon isang bagsakan. Every 15 days they will deliver precisely because of the very limited supply in the global supply chain.”

“Kaya ako humihingi ng pang-unawa mula sa ating mga manggagawa sa sector ng kalusugan. Ito pong nakukuhang donasyon ay patinigi-tingi din.”

When President Rodrigo Duterte placed the National Capital Region under community quarantine on March 12, he thanked China for its willingness to help a strong ally.

The help arrived. Test kits and the much-needed PPEs are now in the country.

“Merong 10,000 PPEs galing sa China kahapon. Ngunit hindi naman kumpleto dahil 'yung goggles niya, 403 lang. Tapos 'yung kaniyang shoe cover ay hindi rin kumpleto. So maghahanap pa kami ng mga sapat na bilang ng mga goggles at shoe cover para makumpleto,” Duque says.

“Pero meron na rin tayong tinatawag na risk-based PPEs. Na kahit hindi kumpleto 'yung PPEs at the same time hindi naman masyadong high risk 'yung pasyente, puwede pa ring alagaan ng ating health workers. Puwede naman na hindi kumpleto yung PPEs, basta meron lang mask, face shield, gloves at goggles.”

But help, no matter how big, sometimes just comes a tad too late.

“You have very many poignant stories about doctors, healthcare workers who put their lives on the line in the service of their fellow men. In doing so, they have been infected and some have lost their lives,” he says.

Reports are sent to Duque’s home office every day.

The challenge of an enhanced community quarantine. Testing capabilities. The controversies surrounding it. More infections. Deaths. The reports never stop. The numbers only grow.

But while fatalities remain faceless, the pain becomes too much to bear when you learn that one’s death happened in the course of performing a sworn duty.

“I have been told of a fellow, a doctor, has died. Siya ‘yong only 34 years old. I really cannot put into words my sympathy. That is an irreplaceable life,” Duque says.

And contrary to how he carries himself in high-level meetings, in the confines of his abode, he finally admits one thing: he is tired.

“I pray. And I always wish that sooner rather than later, this whole thing will end so that the suffering of the world is stopped. This is a global phenomenon, you know. Nobody anticipated this. No one can ever anticipate something of this magnitude would even happen,” he says.

“I tell myself that I need to be strong for the nation. I need to be strong for our people. I take a deep breath every now and then.”

At 10 in the evening of every day, before he sleeps, Duque looks back on the day that’s passed.

If there’s anything that leaves him in awe, it’s not the numbers which grow exponentially each day; it’s the healthcare workers.

“Alam ko mahirap 'yung kanilang dinadaanan. Alam ko malaki ‘yong sakripisyo to care for our patients whom they have sworn to serve. They are living heroes. Sterling. Exemplars of a dedicated and committed public service that they continue to manifest even in the most difficult and trying times,” he says.

“We will acknowledge them in due time for the heroic deeds.”

The general wants victory in this war.

When that will happen, he can’t say just yet.

The fallen

March 21.

It was Annie’s “rest day”.

A rare one in a time of unrest.

Whenever she’s off duty from her hospital work in the province, Annie (who agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity) mostly spends her time tinkering with her phone.

A day that was supposed to be no different.

She read up on the COVID-19 crisis that has gripped the whole world. Scrolling on social media timelines, browsing news articles and clicking on memes her friends have posted.

Then, all of a sudden, she stopped.

A photo of a candle with a black backdrop. Then another one. One after the other.

“Ang daming black profiles. Black na may kandila. Tapos may sinabi doon na a 'doctor has fallen'. Parang hindi na maganda 'yung pakiramdam ko kasi may colleague ako na alam kong mino-monitor,” she says.

News quickly spread that morning.

Turns out, March 21 would forever be different for her.

The flashing headlines screamed at her with fury: PH200 has died from COVID-19. The youngest fatality so far in the Philippines at age 34.

PH200 was the name given by the health department to a patient infected by the coronavirus. The 200th case.

Annie knew PH200 by a different name: “gentle giant”.

Annie and her gentle giant have known each other since 2007, back when they were medical students full of idealism and aspirations in a state-run university.

PH200 wanted to become a doctor not because it pays well, but because it was his “calling”.

“After med school, hindi muna siya nag-start mag-work. Nag-apply siya as a doctor to the barrio. Isa siya sa mga doctors na dine-deploy doon sa mga very rural areas of the country,” Annie recounts.

“We both planned na babalik kami sa kani-kaniya naming probinsiya to serve. Ako pupunta ng Olongapo, siya pupunta ng Nueva Ecija. Babalik siya para mag-serve."

They parted ways after med school. But their friendship was never lost. Annie and PH200 would still cross paths in medical conventions, and even quiz bees. They would keep exchanging messages even as simple as to say hello.

Notifications of “Hi! Kumusta na?” would often pop up on her screen.

In 2018, they reunited during their pre-fellowship in one of the government specialty hospitals in Quezon City. For two weeks, they were almost inseparable and bonded over their shared dream of becoming cardiologists.

“We have the same journey. In the future, sabi namin sa isa't isa, we’ll both be cardiologists. We'll help the people,” she says.

PH200 was one who never gave up easily. Coming from a middle-class family, he supported his own education and earned his medical degree from scholarships.

He was always at the top of his class.

While they didn’t end up spending their fellowship in the same hospital, Annie and PH200 remained in touch. As incoming juniors, they were just one step closer to their dreams.

Then, the virus happened and those dreams were dashed.

Annie is graduating from her fellowship next year. Alone.

The death of a close friend is gut-wrenching enough. But a death from COVID-19 is even more unbearable. There aren’t any bodies to say goodbye to. Those who die from the disease are cremated immediately to kill the virus that can still potentially infect others.

For Annie, all she can hold onto is the image of her friend: kind-hearted, calm and approachable. Her gentle giant.

“Kanina, I saw the pictures posted by my batchmates na parang nu'ng nakita ko siya, it seems as if he's not yet gone,” she says.

PH200’s journey may have been cut short. Annie says she is extremely blessed to have been part of it.

He was like her brother. And now, he can rest.

“May isang araw na sobrang pagod kami. We went to a mall to buy comfortable shoes. Sabi ko, 'Hiwalay muna tayo, but then sabi niya, 'Naku, kailangan mo akong tulungan maghanap ng magandang shoes ko.' Ako iyong namili ng shoes sa kanya. Kasi sabi niya gusto niya magkaroon ako ng opinion. Parang mas feel niya na ibang tao ‘yong titingin na maganda ang suot niya,” she recalls.

“He would say, mag-buffet kami. Pagkain ‘yong pinag-uusapan din namin kasi sa sobrang pagod namin, we feel we both deserve na kumain ng masarap. Pero siya kasi natanggap sa hospital sa Quezon City. Ako, bumalik sa hospital sa Pampanga. Hindi na natuloy 'yung plan namin to eat together.”

As many health workers continue to risk their lives to save others, they pin their hopes on the likes of PH200. Annie, a frontliner herself, was praying PH200 would be the “poster boy” of a successful battle against COVID-19.

“Iniisip namin na sana makayanan niya. Lahat kami nagkakasakit but usually nakakayanan naman namin. So we were all expecting he would recover. Kaming mga kaibigan niya, mga kaklase niya are thinking he has to recover kasi if he does, knowing na critical na siya, there will be hope. Ibig sabihin malalagpasan ng mga taong may sakit ang COVID,” she says.

“Habang hindi pa tapos itong pandemic, siya ‘yong iniisip naming hope na lahat ng tao makakayanan ito.”

PH200 put up a good fight. But if there’s anything Annie wishes she could have done during his ordeal, it was to visit him; to comfort and tell him everything was going to be all right.

For a vocation that cares and stands by a patient during their most vulnerable times, PH200 would have expected to experience the same.

But in his last moments, a time when he needed comfort the most, no one was allowed near him. Not even his family.

“For sure he wanted someone; family, friends to be there. ‘Yun ‘yong malungkot hindi lang para sa kaniya. Kasi the reality of being a COVID patient is that you die alone.”

“No one deserves to suffer alone. We don’t want to have that experience of dying or suffering alone.”

As the number of infections continues to rise, Annie admits their morale is headed the opposite direction. Fear has crept in the hearts of most of the country’s healthcare workers.

Frontliners such as her depend on a system that is set out to protect them. And even as the virus spreads wildly out of control, the same system is supposed to keep her ranks standing tall.

For the health workers in mourning, this clearly isn’t the case.

“That's the sad thing about the healthcare system. We don’t have that much supplies. Titipirin na lang kami. So, parang how would you protect yourself, kung mismo 'yung system, they're not protecting us? Kung meron man, konti lang.” she laments.

“Siguro even when this pandemic ends, we would just have to be more careful, lalo na sa mga airborne and droplet infections. You will see sa state ng kahit sino sa amin, we’re very vulnerable. It could happen to anyone of us.”

March 22.

Annie received news of another death of a healthcare worker.

As the days drag on, those like Annie are tempted to turn their backs and walk away. But how can they do so when the likes of PH200 have made the ultimate sacrifice in the name of public service?

Forging bravely on at the frontlines will surely be excruciating in the coming months. But for Annie, it’s a burden she must carry.

“Kaming mga kaibigan ni PH200, pati mga natitirang healthcare workers, we will still fight. Para malabanan ‘tong COVID, para wala nang mai-infect. Para wala na din taong magsa-suffer. We just want this to end kasi andami nang namatay. Para hindi maging in vain 'yung pagkamatay niya,” she says.

The cleaner

“Mag-ano ka, ganito gawin mo araw-araw. Maligo ka, kumain ka nang marami, mag-vitamins ka.”

“Opo, Mama, gagawin ko po.”

There was hardly enough time for Marissa to prepare her 11-year-old son how to survive on his own.

It was the eve before the lockdown. In a matter of hours, Luzon -- an island that's home to almost half of the Philippines’ population of 109 million people -- will grind to a halt as the government ramps up efforts to stop the rapid spread of the coronavirus.

With residents confined to their own homes, businesses closed, and mass public transportation suspended, the hospital Marissa works for advised them to stay in the hospital rather than risk walking out on the streets every day.

That meant that she only had a few hours to grab some clothes and talk to her son.

As difficult as it was, Marissa had little choice but to live with the arrangement. She has to make a living for her family.

Marissa took comfort at the thought she could rely on her son.

She was supposed to take him to the province so relatives could take care of him while she worked. She had already sent her daughter there earlier. But her son wanted to stay in Manila for his graduation scheduled at the end of the month.

But then the lockdown happened. No one enters, no one leaves the nation’s capital region. And with large gatherings banned, there’s no graduation. No march on stage so parents can beam with pride and see the fruits of their children's hard work.

Marissa’s work as a cleaner -- or housekeeper as they are called in her hospital -- puts her at the frontline against a virus that nobody fully understands just yet.

In her case, she is assigned to the area where persons suspected of having contracted the virus are brought to be examined and assessed by the doctors.

Patients don’t stay long though, as they are usually moved to another area. But the high volume of people coming in and out translates to as many times she would have to change the bedsheets, scrub the floor and disinfect all surfaces.

Despite the high risk, Marissa doesn’t mind.

“Noong una, natakot ako. Pero ano po naman kami, sinisigurado ng ano namin na magiging maayos kami. Meron naman po kaming personal protective equipment,” she says.

“Bago naman po nangyari, meron na po kaming training kung anong klaseng virus. Virus po, so droplet. Di ka naman mahahawaan kung di mo nakasalamuha o wala kang contact,” she explains, sounding even more confident than some doctors.

But she takes precautions. Back when she would still go home daily, she would shower before leaving the hospital. And she would try not to stay too close to her son.

Still, the thought of getting infected by any disease gets to her sometimes.

“Paano 'pag ako naging ano (infected), paano ‘yong anak ko?” she says.

Marissa once tried leaving the hospital for a job at a bank. Same chore – cleaning the premises, keeping everything tidy and in order. But it didn’t last long. She went back to another hospital.

“Ewan ko ba kung bakit, kung ano'ng meron at ginusto ko 'to. Di rin naman ako magtatagal kung di dahil sa samahan din,” she explains.

She does have plans of leaving the country, perhaps next year, she says, for work also in a hospital in Dubai.

“Pero kung P30,000 lang ang sahod, dito na lang ako,” she says.

But those thoughts are far ahead into the future.

For now, her two children remain foremost on her mind, even as she braves the risk day in, day out.

She would call her daughter twice a week and her son twice a day, sending money to her landlord with a request to check up on him.

“'Yung pong mga anak ko, siyempre, kung paano sila? Sa barangay namin, may isa nang confirmed. Nag-aalala ako kaso wala kang choice. Sinasabihan ko sila huwag na lang lumabas ng bahay,” she says.

It doesn’t help that even her own neighbors are discouraging her from going home.

“Mga kapitbahay ko du'n, takot sa akin kasi galing daw po akong ospital,” she says of her neighbors whom she has known for 12 years.

“Nakakalungkot po. Di nila kinonsider sitwasyon ko. Di ko rin naman sila masisisi. Nagtatrabaho naman din ako sa ospital.”

Several of her hospital’s patients have tested positive for the virus.

How much longer will they survive this way? Marissa could only guess.

Like everybody else, she’s taking it a day at a time.

Days that would hopefully lead to her family becoming complete again and all of them under one roof.

She hasn’t given up. She refuses to lose hope.

There are far bigger dreams to live for.