TAGAYTAY, Cavite - The pitch black fumes belching from the crater of Taal volcano have long been exhausted, but survivors of the 42nd eruption of the Philippines' second most active volcano continue to grapple with the effects of the disaster, now worsened by a pandemic.

While provinces cloaked in thick mud and hot ash in January recorded few COVID-19 cases, some farmers, retailers, and restaurateurs in Southern Tagalog face mounting uncertainty as the twin crises — due to a volcano and a virus — discouraged tourists and investors from traveling to the once-bustling, agri-entrepreneurship cauldron off the borders of Metro Manila.

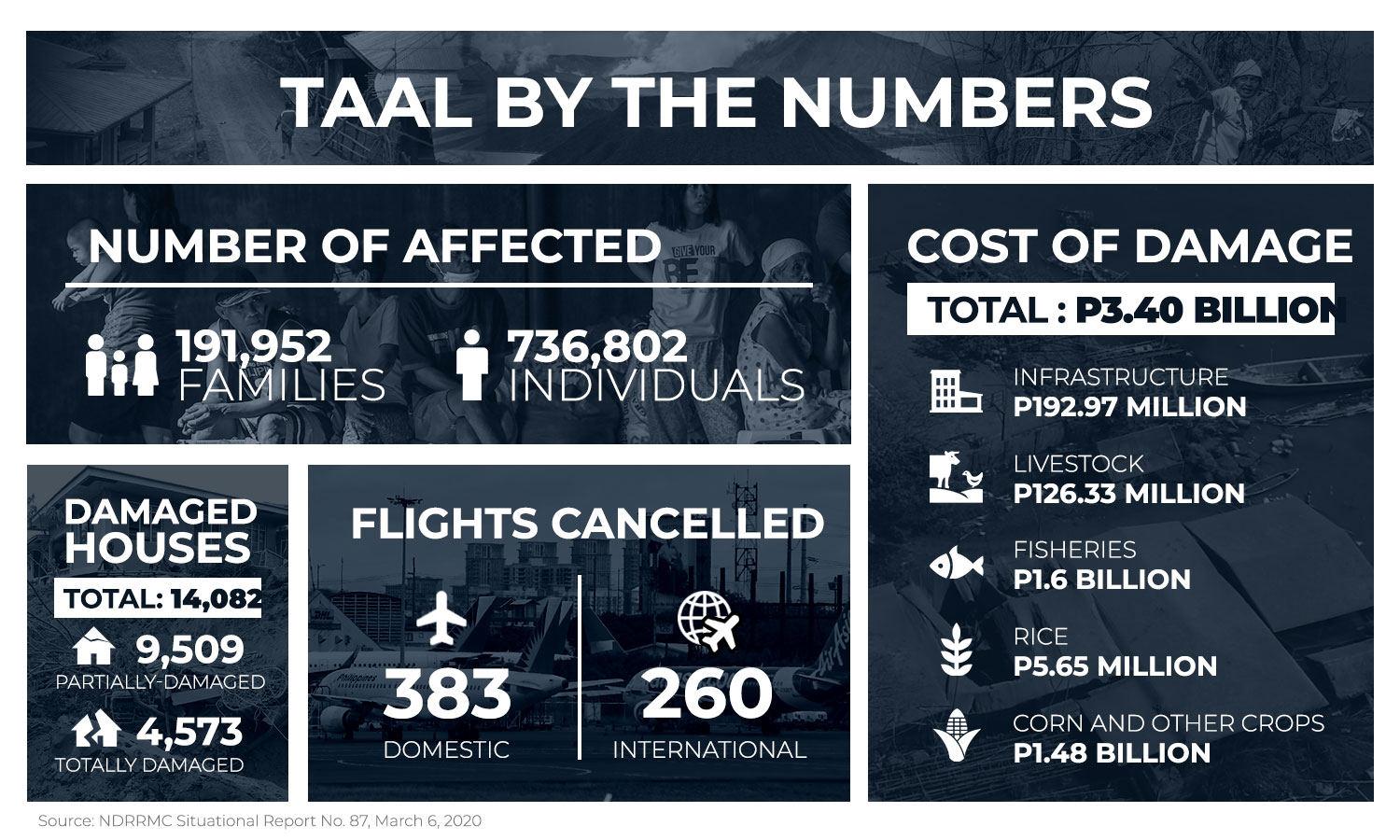

With 736,802 displaced individuals, 14,082 wrecked houses, and P3.40 billion worth of infrastructure and agriculture damage, those who overcame the January 12 eruption are now challenged to find ways to rebuild their lives and livelihoods under the new normal.

I. TAAL'S HORSEMEN

Horseman Ernesto Dalumpines trudged along a dirt road in a lakeside town in mainland Batangas, but instead of mounting his steed the 58-year-old hopped on a tricycle, his new source of livelihood after Taal volcano's eruption wiped out their village that depended on offering tourists horseback rides to the crater.

Dalumpines used to own 6 horses, but he only managed to save half of them days after the Philippines' second most active volcano spewed lava and hot rocks, blanketing most of the island and 3 nearby provinces with volcanic grime.

"Ang naligtas na lang ay 3 [kabayo] dahil natabunan na yung iba," Dalumpines said.

(We only saved 3 horses because the other horses were already buried alive in ash.)

"Yung mga natira naming kabayo, mga gutom sila tapos parang nagka-phobia, mga takot na sa tao," he said.

(The horses that survived were starving, and they seem to have developed a phobia, because they are no longer domesticated.)

Horses trapped on the island volcano during the eruption are rescued on January 17, 2020, while the volcano actively simmers. Jonathan Cellona, ABS-CBN News

Dalumpines' horses have been temporarily taking shelter at a nearby ranch in the town of Talisay, a boat ride away from the volcano island, while his wife and 5 children were evacuated to an unfinished school building in the same municipality.

With blankets as partitions and used cardboards as beds, Dalumpines' brood and about 50 other families have built makeshift homes in the 2-story building across Taal island, where they once thrived as horsemen, farmers and fisherfolk.

"Malaking pagkakaiba kasi iba talaga pag sarili mong bahay," he said.

(It is really different when you are not living in your own home.)

"Dito talagang hindi ka makakagalaw ng husto dahil, una, ang daming tao, tapos hindi mo sariling bahay," he said.

(It's hard to move around here, because it is congested and we have to share the space with everybody.)

Their blankets, clothes and cookware were mostly donated. He managed to buy a tricycle by loaning P40,000 ($800) from several relatives.

"Wala akong ibang maisipan... 'yun talaga iniisip ko, yung gastusan namin," he said.

(I could not think of anything else... all I thought about was how I could earn for our daily expenses.)

Dalumpines said he bought a tricycle thinking he can earn by transporting children to school, but the outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) stalled his plans as the government banned students from physically attending classes to avoid the possible spread of the virus.

"Sa ngayon po hirap na hirap kami. Para kaming nanghuhula kung saan kukuha ng pasahero, napakadalang talaga gawa nung COVID," he said.

(As of now, we are really in a tight position. We can only guess where we can find passengers because there aren't a lot of people on the streets due to COVID.)

"Ang hirap talaga [lalo sa] financial at pagkain talaga," he said.

(It's been difficult, especially when it comes to financial and finding food.)

On a good day, Dalumpines brings home about P300 ($6), only a 10th of what he used to earn when he was still a tour guide in the volcano island.

Then, each tourist would pay P500 ($10) for a horseback ride to the crater. With half a dozen horses, Dalumpines used to earn P3,000 ($60) on some days, and even double during holidays.

"Mas mainam yung sa turista [kami nabubuhay] kasi nag-aantay ka lang doon tapos iaakyat mo lang sa bulkan tapos magkakaroon ka na ng pera," he said.

(It was easier when we still depended on tourism on the island because all we had to do to earn money was to wait for tourists to come, then take them up to the volcano.)

"Kung maganda at galante pa yung guest, nagbibigay pa sa amin ng tip," he said.

(If the guest is generous, we would even receive tips.)

Dalumpines said selling their family's 3 remaining horses is not an option for now.

"Naaawa yung mga anak ko. Parang kasama na kasi namin sa buhay yung mga kabayo," he said.

(My children have an attachment to the horses. We treat those horses as our companions.)

"Sila ang tumutulong sa amin noon... Lalo kapag walang wala," he said.

(They have helped us, especially when we had nothing.)

With his meager income as a tricycle driver in the mainland, 3 of his 5 children have dropped out of school. His 22-year-old son sails to the lake with his cousins to fish, while his 2 teenage children help their mother sell siomai (dimsum) at the evacuation center.

Dalumpines is still uncertain if he can afford to buy either a smartphone, a television or a transistor radio that will help his 2 youngest children, who are about to enter Grade 8 and junior high school, learn as the Philippines shifts to a distance-learning system.

"Talagang napakahirap. Wala naman kaming magagawa dahil sakuna ito," he said.

(These are very hard times. We can't do anything about it because it’s a calamity.)

"Bahala na ang Diyos kung ano ang buhay namin dito."

(Only God knows how we can live here.)

II. TALISAY'S FISHERMEN

Boots Goneo and his men, who were living near the Talisay fishport, were unharmed during the eruption, but their fish cages in the middle of the freshwater lake were not spared from the ashfall.

The fish — about 100,000 pieces of live tilapia and bangus — swam free after the cages' buoys sank under the weight of volcanic debris.

"Yung mga fingerlings, maraming namatay dahil lumubog yung cage [dahil sa] ashfall," Goneo said.

(A lot of fingerlings died because the cages sank due to the ashfall.)

"Milyon-milyon ang nawala," he said.

(We lost millions’ worth of fish and fingerlings.)

The Department of Agriculture has released P160 million in aid for farmers and fisherfolk hit by Taal's eruption, but the sum is only a 10th of the P1.6-billion damage to Batangas' fishing industry, according to data from the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC).

Six months after Taal volcano's unrest, some fisheries in Batangas have yet to recover their losses, Goneo said.

"Kulang kami ng supply ng fingerlings doon [sa Batangas], dahil nagkaproblema yung mga hatchery sa Laguna," Goneo said.

(We still lack fingerlings in Batangas because there were also problems in the hatcheries in Laguna.)

"Walang gaanong makuha na fingerlings mula noong March hanggang June... [dahil] apektado na din 'yun dahil sa abo ng Taal at init ng araw, namatay mga fingerlings," he said.

(We have had a hard time procuring fingerlings since March until June... because a lot of fingerlings were killed because of Taal's ash and hot weather.)

Besides fingerlings, investors have also been scarce, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic began, said Goneo, who is now stationed in Bulacan, far from the threat of a dormant volcano.

"Yung mga investor kumonti [pagkatapos magkaroon ng COVID-19] dahil nag-atrasan 'yung iba," he said.

(There aren’t many investors after COVID-19, because some backed out from deals.)

"Tumumal ang market ng tilapia... baka walang pera ang mga tao," he said.

(The market for tilapia dwindled... maybe because money is now hard to come by.)

The sun sets on Taal Lake on January 27, 2020. Fishermen, both in the fish farms and traditional lake fishing, adjust to the realities brought by the disruptions, initially by the eruption of Taal Volcano and then the COVID-19 pandemic. Jonathan Cellona, ABS-CBN News

Several businesses in Metro Manila and parts of the country were forced to either scale down or declare bankruptcy after non-essential businesses — including aviation, retail and construction — were barred from operating during the Philippines' 45-day lockdown.

The Philippine economy is expected to shrink by as much as 3.4 percent in 2020, the Department of Budget and Management said in May.

The lockdown in Metro Manila — a region that accounts for a third of the Philippines' gross domestic product — will likely lose up to P2 trillion, the agency said.

Some 7.3 million Filipinos have become jobless during this year's economic crisis, mostly due to the Philippines imposing one of the world's longest COVID-19 lockdowns.

Goneo has turned to online referrals and social media advertising as he continues to search for capitalists who may be willing to invest in aqua farming in the middle of the global crisis.

"Madali lang naman bumawi basta huwag ka titigil. Yun ang pinaka the best doon, huwag kang titigil," he said.

(It is easy to recover as long as you don't stop. The best path to recovery is not stopping.)

"Kailangan tuloy-tuloy ka. Pag tumigil ka, lahat ng pangarap mo tigil na rin."

(You have to keep on going. If you stop, all your dreams will also be put to a halt.)

III. BATANGAS' GARDENERS

While many businesses near Taal volcano were affected by its eruption, some sectors have prospered.

Shortly after the eruption, Roberto Mangubat's plant nursery across the volcano island was shrouded in hot ash, but 6 months and 2 lockdowns later, the 68-year-old gardener's business is now thriving after Filipinos developed a penchant for plants while in quarantine.

While some of his saplings died after their leaves were seared by volcanic debris, Mangubat recovered his losses after the national government imposed a Luzon-wide lockdown in mid-March.

"Sa lockdown na ito, nagkabiglaan, ang daming bumili... Libuhan ang nabenta," he said.

(During the lockdown, we were surprised that a lot of people bought plants... We sold thousands.)

"Lahat ng maghahalaman lumakas ang benta. Idinaan nila sa online, ang daming bumili sa online kaya ang daming kumita sa halaman," he said.

(All plant sellers saw their sales increase. They sold their goods online and people bought, so a lot of us earned.)

In 20 days or less, Mangubat earns at least P10,000 ($205) from selling mahogany and coffee saplings, flowering plants and indoor shrubs.

The ornamental plant industry in the Philippines "boomed" during the enhanced community quarantine as some Filipinos stuck at home turned to gardening as a form of diversion while at home, the Department of Agriculture has said.

The government has yet to measure the growth rate of the gardening industry during the pandemic, but Mangubat said he is already in the process of shifting to selling ornamental plants instead of shrubs.

A coffee sapling sells for only P4 ($0.08) a piece, while ornamental plants go for as much as P200 ($4), he said.

Mangubat said he plans to stay at his lake-side residence and tend to his potted goods, not worried that another eruption could happen.

"Dito lang kami. Wala naman akong pupuntahang iba dahil ito lang ang hanapbuhay ko," he said, noting that most of his 10 children are already living with their own families in different cities.

(We will stay here. I have nowhere else to go because this is my livelihood.)

"Matanda na ako. Ako nahihirapan, gusto ko tumigil na pero lalo akong manghihina kapag ako ay tumigil."

(I am old. It hasn’t been easy and I want to stop working, but I believe that I’ll feel weaker by doing nothing.)

IV. AMADEO'S FARMERS

Reynaldo Villanueva grunted under the noontime sun as he chopped off stunted pineapples from peduncles that were not spared from being seared by Taal's hot ash, even if his farm in Amadeo town, Cavite was 30 kilometers away from the volcano.

What used to be football-sized pineapples are now barely larger than the farmer's palm after the volcano's ash cloaked the fields, stripping nutrition off the fruits.

Before the ashfall, a pineapple from Villanueva's farm sold for as much as P55 ($1) per piece, but now most of the fruits are only priced between P10 ($0.20) and P20 ($0.40).

"Halos kalahati lang ang nilaki [nung mga pinya]," Villanueva said.

(The pineapples barely grew to half their usual size.)

"Siyempre wala naman kami magagawa ng pamilya ko... Nagtiis na lang talaga kami sa lugi," he said.

(My family can't do anything about it... We just have to bear the losses.)

A pineapple plantation in Amadeo town, Cavite, is covered in ash in the days following the eruption of Taal Volcano. Jonathan Cellona, ABS-CBN News

Crop damage in Cavite due to the volcano's eruption was pegged at P1.02 billion, while Batangas' losses were estimated at P341.05 million, March 2020 data from the NDRRMC show.

The government earmarked P30 million to provide zero-interest loan packages for Taal-hit farmers, but each of them can only borrow up to P25,000, according to the Department of Agriculture.

Villanueva needed about P300,000 to rehabilitate his pineapple farm since he was not tilling his own land, and had to give a fifth of his earnings to the landlord.

"Umutang ulit ako ngayon, yun yung ipambabayad ko sa nalugi sa akin," he said.

(I borrowed more money so I can make up for the losses.)

"Walang magagawa [kung di mangutang]. Talo gawa ng nadali ng bulkan," he said.

(I can't do anything but borrow more money. I suffered losses because the volcano damaged my crops.)

With piling debt and nearly no income, Villanueva plans to convert his pineapple plantation to a corn and peanut field to make money faster.

A farmer sprays his plants with water to wash off the ash on his pineapple plants in Amadeo town, Cavite, on January 22, 2020. George Calvelo, ABS-CBN News

"Mahina ang kita sa mani at mais kaya nga lang, mas maganda na din yung mayroon konting kikitain," Villanueva said, noting that he can harvest these crops sooner compared to pineapples.

(Harvesting peanut and corn reaps a smaller income, but that's better than having nothing.)

Finding a job other than farming or relocating to another province is not an option for Villanueva, who has been tending to his pineapple field for 3 decades.

"Minulat na sakin nung mga magulang ko ang pagtatanim," he said.

(My parents raised me through farming and as a farmer.)

"Wala naman akong alam na ibang trabaho kaya hanggang diyan na lang talaga."

(I don't know any other job so I have no choice but to settle with this.)

V. BATANGAS' COFFEE GROWERS

Randy Mendoza took pride in the Robusta and Barako beans that grew in his backyard farm, but the blistering dirt from the Taal eruption also scorched his coffee and banana trees, leaving his family with no harvest for 5 months.

Mendoza lost about P100,000 ($2,034) in potential income, and has been using his family's savings and relief goods to survive the crisis.

"Tipid ang paggastos namin... Bukod sa tulong ng gobyerno, meron din kaming mga tanim at alagang manok na puwede iluto 'pag wala na talaga," he said.

(We’re mindful of our spending... Besides government aid, we also have backyard vegetables and live chickens we can cook if ever our funds run out.)

Mendoza's shrubs were among Calabarzon's 10 million coffee trees that produced at least a ton of beans each month, which made the region the Philippines' sixth largest producer of the said kibble, according to a Department of Agriculture study uploaded in 2019.

In 2015 alone, the region produced 1,136 metric tons of coffee beans, data show.

Six months after Taal's eruption, green leaves have slowly sprouted back on Villanueva's coffee trees, but the shrubs have yet to bear fruit.

"This year, baka wala [nang harvest ng kape dito sa Cavite] kasi natuyo 'yung mga dahon," he said.

(Maybe we can't harvest any coffee beans this year because some of the leaves are still dry.)

A farmer shows a coffee bean recovered from a farm covered in ash. Beans from plants that bloomed before the eruption can still be harvested, but the plants that dried up will need at least a year to bear fruit again if they were not damaged. George Calvelo, ABS-CBN News

It will take 3 to 4 years to grow new coffee saplings into trees and another year before it can bear fruit again, said the 59-year-old farmer.

The few cans of coffee beans his family managed to save and roast before the Taal even have been kept in storage for months after cafés and restaurants were forced to shut down for nearly 3 months due to the threat of COVID-19.

"Bumagsak 'yung price kasi nung COVID, maraming restaurant ang nagsara, mga hotel, maraming coffee shop na nagsara so yung kaniyang price, bumagsak," he said.

(The price dropped because restaurants, hotels, and coffee shops were closed because of COVID-19.)

A coffeeshop in Amadeo town, Cavite is temporarily shut on January 23, 2020, as the plantation it is attached to tries to recover from the disaster. George Calvelo, ABS-CBN News

"Malaki ang gastos namin sa [pag-aalaga sa] kape. One year 'yan bago mamunga kaya hinihintay pa namin yung higher price... para kumita din kami kahit papaano," he said.

(It is costly to care for coffee trees. You can only harvest their beans once a year so we have to wait for a higher market price so we can still make profit.)

While Mendoza waits for coffee shops to start reordering beans from his farm, he provides for his family by selling bananas and guyabanos.

"Meron kaming kaunti na naitatabi na kaunting ipon so ’yun na lang ang aming pinagkakasya," he said.

(We set aside some money, and we find a way to budget that.)

But just like other farmers who have been reeling from Taal's destructive ash, Mendoza has no plans to give up on his farm.

"Basta't dasal lang... Konting sipag din kung ikaw ay nagbubukid. Sabi nga nila, di ba, kung hindi ka magtatanim, wala kang aanihin."

(We just have to pray. If you're a farmer, you have to put in hard work, too. Make sure you plant something now, so there’s something to harvest later.)

VI. TAGAYTAY'S TOURISM

The volcanic grime that once smeared the roof and walls of the hotel and restaurant Steven Cruz (not his real name) managed in Tagaytay City have been scrubbed off, but the cliff-side building once brimming with weekenders remain hushed half a year after Taal volcano sent guests fleeing from its menacing fumes.

Cruz and his team spent days repackaging the muddied hotel to sweep away vacationers' worries over the dormant volcano, but only a week after reopening, they — and other tourism establishments near the volcano — had no choice but to stop operations for the second time in 3 months.

"Target namin na sana makabawi this year o kaya sa susunod na taon," Cruz said.

(We were targeting to make up for our losses this year or next year.)

"Dapat operational na tayo after a week nung sa Taal, kaso inannounce na naman yung COVID," he said.

(We were supposed to be operating a week after the Taal eruption, but then COVID happened.)

Hotels and establishments deemed non-essential were ordered closed in mid-March after the national government locked down Luzon — the Philippines’ most populous island — to arrest the spread of the highly contagious virus.

Cruz's business is only one of 56 hotels in Tagaytay hit by the 2-fold setback. A total of 2,295 other establishments that flourished on tourism receipts were also victims of the twin catastrophes.

A restaurant is temporarily closed, as Taal Volcano simmers in the background on January 16, 2020. Jonathan Cellona, ABS-CBN News

Service-related businesses within the 17-kilometer radius of the volcano lost P2.77 billion after they were ordered shut shortly after the volcanic eruption, data from the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) show.

But with the COVID-19 lockdown, the country's entire service sector fell by P589.7 billion, NEDA said.

"Napakahirap kung paano kami maghihikayat ng tao na bumalik dito," Cruz said.

(It is so hard to convince people to come back here.)

"Mas lalo ngayong may COVID kasi yung Taal, puwede nila balikan 'pag hindi na nabuga 'yan. Dito sa COVID, lagi silang alangan," he said.

(It is more difficult with COVID because with the Taal eruption, people can easily come here once they see that the volcano is no longer rumbling. With COVID, they are always hesitant.)

The local government has been trying to market the cliff-side city as a destination safe for both tourists and residents to help businesses recover their losses, Tagaytay City Health officer-in-charge Liza Capupus told ABS-CBN News.

Businesses have been required to check every customer's temperature at the storefront, and have their shoes and hands sanitized before entering the store.

Operations of commercial establishments are limited to 30 percent to ensure there will be proper physical distancing at cafés and restaurants.

"We will be allowing the economy to again grow but at the same time, we have to make sure that people are protected when they go inside Tagaytay," Capupus said.

"We want to tell people, 'Hey, you could come to Tagaytay because Tagaytay is safe.' But we should also know that they are safe, na hindi din nila mahahawahan yung mga taga-Tagaytay (that they will not infect Tagaytay residents)," she said.

The early stockpiling of medical supplies — including face masks, hazmat suits and COVID-19 test kits — and the strict enforcement of quarantine policies have resulted in Tagaytay having only 17 COVID-19 cases as of mid-July, according to data from the City Health Office.

While restaurants in the city were already allowed to operate, hotels remained closed, forcing several establishments to lay off some workers.

Cruz had to let go of about 7 employees.

"Itong buong taon na ito, wala talaga. Walang kinita. Bagsak," he said.

(This entire year have brought us nothing. No earnings at all. Business is really down.)

"Mahirap kalaban ang kalikasan... Pag ang kalikasan ang kinalaban mo, mahirap, lalo na itong pandemic natin, hindi natin nakikita sino ang kalaban natin."

(Nature is a formidable adversary, this pandemic in particular because you can’t see what you’re up against.)

VII. TAGAYTAY'S EVENTS INDUSTRY

Caterer Willie Gatpandan's commissary in Tagaytay was once bustling with chefs who cooked for wedding banquets and parties in one of the events capitals of Luzon, but after the twin crises his kitchen is now filled with packed food and pastries ready for online selling.

Gatpandan shelved his events place and catering business to sell raw meat and cold cuts, while his staff have been using the commissary to sell their own goods.

"Karamihan ng staff namin nabubuhay ngayon sa online selling," Gatpandan told ABS-CBN News.

(Most of our staff are making a living nowadays through online selling.)

"'Yung mga cook namin, luto nang luto, 'yung mga waiter namin, ginagawa nilang reseller,"

(Our cooks prepare the dishes, while our waiters resell them.)

Tagaytay's wedding industry has been "stripped off its glamour" as other events suppliers have also shifted to selling necessities while mass gatherings remain prohibited because a COVID-19 vaccine has yet to be approved and distributed.

An events coordinator is now selling fish, while a wedding florist has turned to planting pineapples and indoor plants in his yard. A group of photographers pooled together their savings to open a small online grocery website.

"'Yung wedding industry, parang back to zero. Parang lahat kasi ng talent nila (suppliers), hindi mapakinabangan ngayon," Gatpandan said.

(Wedding supplies have essentially gone back to zero, because their talents as wedding suppliers are useless.)

Wedding venues, such as Willie Gatpandan's new restaurant, are using the downtime caused by the Taal eruption and the pandemic to build or refurbish their places. Jonathan Cellona, ABS-CBN News

"Nandoon sila sa point na, ‘Kahit minimum lang may kitain lang ako’," he said.

(They are at a point where they’ll settle for the minimum just have money.)

Wedding suppliers are part of the audio-visual and events industry, which accounts for about 6.52 percent of the Philippines' gross domestic product, according to data from the Film Development Council of the Philippines (FDCP).

In the first 5 months of 2020 alone, the industry already lost P100 billion, hitting the livelihood of at least 760,000 workers, FDCP chair Liza Diño has said.

The industry needs help and support from the government as it is "the first to be canceled and... the last to recover" because the sector earns through mass gatherings, she said.

Before Taal erupted and the pandemic broke out, Gatpandan's cliff-side events place used to have 25 bookings per month.

While Gatpandan managed to rebook a quarter of those events for next year, he still lost some P4 million in refunds.

People in the wedding industry are optimistic Tagaytay will regain its reputation as a primary destination for wedding ceremonies and receptions. Jonathan Cellona, ABS-CBN News

"Ang chance na lang namin ay yung restaurant [namin] at 'yung nagbebenta kami ng mga kailangan," he said.

"Kailangan talagang matutunan how to adapt to the new normal. Ang iba kasi ang pagkakamali nila, hinihintay nila bumalik yung normal.

"Kung gusto mo mag-move on, ngayon pa lang i-accept mo na na hindi na talaga babalik ang normal. Ito na talaga ang buhay ng tao.”

(Having the restaurant and selling essentials are what’s keeping us afloat. The mistake people make is to wait until things go back to normal, but we need to find a way to adapt now. If we accept that this is the new reality we’re in, moving on with life will be much easier.)

VIII. AGONCILLO'S HOG RAISERS

Days after Taal’s eruption, relatives Benito Enriquez and Crispin Cunese were drenched in sweat as they chased the remaining hogs in their pen that collapsed under the weight of thick ash.

The two men hauled one swine after another into a rented jeepney, grunting under their breath: "Iligtas 'yung mga baboy para ligtas din tayo."

(Save the pigs, and save us.)

Selling the pigs was a lifeline for their family during the calamity that sent their wives and children packing to evacuation centers.

"Sadya pong kami ay sa paghahayop talaga," Enriquez said.

(We really live on raising animals.)

"'Yun lang po ang aming ikinabubuhay dito kaya kami po ay kahit ganun, nakikipag sapalaran pa din po," he said, when asked if they plan to relocate away from the volcano.

(That is our lone source of livelihood so even if we're in an unfortunate situation, we will take the risk.)

Benito Enriquez stands in front of the piggery he evacuated when Taal Volcano erupted in January, the same piggery he went back to that is now sustaining his livelihood during the COVID-19 pandemic. Jonathan Cellona, ABS-CBN News

The Taal eruption and the fear that pigs that inhaled volcanic ash might cause health issues plunged pork prices to P60 ($1.23) in Batangas for weeks, further sinking affected families in financial difficulty.

"Talagang sadsad ang presyo ng baboy. Talagang nagtiyaga lang kami," he said.

(The price of pork really went down. We had to make do with it.)

"Dahil marami pa kaming relief noon, talagang tiis na 'yun ang ulam araw-araw," he said, referring to the cans of sardines and instant noodles usually given to calamity victims in the Philippines.

(Because we had a lot of relief goods then, we had to bear with eating it every day.)

Their business turned around about 3 months after the restive volcano calmed down, with the onset of the pandemic.

The price of pork nearly doubled to P160 ($3) a kilo after the government placed the entire Luzon under lockdown to contain the spread of the highly infectious COVID-19.

"Siguro walang mabili yung mga tao. Walang import so medyo tumataas yung presyo ng baboy kasi walang pumapasok na galing sa ibang bansa," Enriquez said.

(Perhaps, there wasn’t a lot of pork available in the market. The prices went up, because pork wasn’t coming in from abroad.)

"Siguro walang mabili yung mga tao. Walang import so medyo tumataas yung presyo ng baboy kasi walang pumapasok na galing sa ibang bansa," Enriquez said.

Cunese and Enriquez pooled the government aid they received together with some relatives to buy new hogs and restart their piggery.

"'Yung pera namin galing sa tulong, iniipon namin," Cunese said.

(We saved the cash aid we got and used it.)

"Tiyaga lang talaga tapos tipid," he said.

(It was a combination of hard work and being smart with our money.)

Crispin Cunese, a relative and business partner of Benito Enriquez, says raising livestock is the only business they know. Jonathan Cellona, ABS-CBN News

Several groups of agriculture stakeholders have urged the Department of Agriculture to temporarily ban the importation of poultry and meat to help local producers recover from the economic effects of the global pandemic.

The government has yet to formally heed the request as of mid-August.

Half a year after the Taal's wrath, the hog raisers in the town of Agoncillo have regained their footing. They have also learned to create safety nets in case the volcano, a hog disease, or another calamity happens.

Enriquez is now raising goats, too.

"Hindi pa naman masasabing asenso dahil hindi pa namin nakikita yung mismong kaluwagan," he said, noting that they are still wary of the African swine fever, which has been plaguing another town in the province.

(We can't say we have totally recovered, because we are still in a tight spot.)

"Pero sana ngayong taon makabawi na kami... Sana dirediretso na yan," he said.

(We do hope, though, that our momentum continues and we recover this year.)

After surviving the 42nd eruption of the Philippines' second most active volcano, Cunese said his industry is now more prepared.

"[Natutunan namin na] kailangan talaga may ipon ka dahil pag ikaw ay busayak, pag dumating ang ganiyang krisis, wala kang makukunan, patay ka," he said.

(We learned that you really need to save money, because if you’re not responsible with your money and you don't have anything during a crisis, you're dead.)

"Handa na talaga kami kahit ano ang dumating dahil kami ay sanay na sa ganiyang sitwasyon."

(We are more prepared for uncertainties now, because we already know what to do when those situations arise.)

ADDITIONAL CREDITS:

Mark Demayo