Thirteen-year-old Mary Cris Dalay cannot exactly remember the series of incidents that happened on the night of December 16, 2011. All she recalls is that it was dark and cold, and they were fighting for their lives as the raging waters of Cagayan River swept their house, with 6 people, out in the open sea.

Exhausted after floating in the water overnight, she fell asleep and woke up at dawn to find herself almost 100 kilometers away on another island, in the province of Camiguin.

Sendong survivor

Her mother and two siblings were not as fortunate. Their bodies remain missing up to this day.

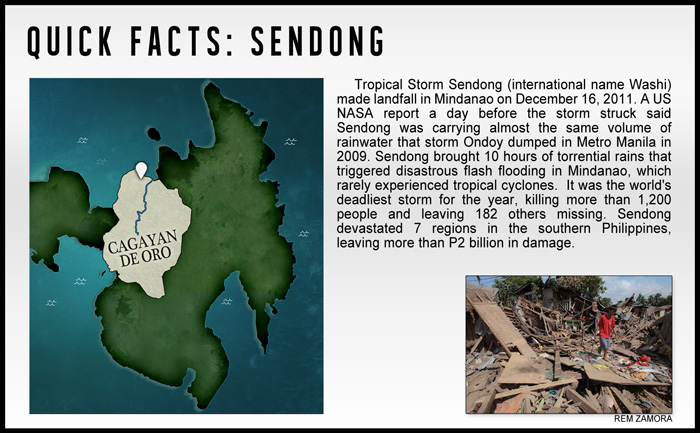

Tropical Storm "Sendong" (Washi) was the 21st tropical cyclone that entered the country in 2011. It is also considered as the strongest that year.

It formed in the Pacific Ocean, around 945 kilometers southeast of Guam on December 13, 2011, and entered the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) on December 15. By December 16, "Sendong" crossed the island of Mindanao, lashing the provinces of Agusan del Sur, Bukidnon, and Misamis Oriental.

"Sendong" left 1,257 dead, 6,071 injured, and 182 missing across 13 provinces in the Philippines.

Close to 900 bodies were found in Cagayan de Oro City, while 408 others were retrieved in Iligan City.

Dalay's house was located in the village of Isla de Oro, which straddles the mouth of Cagayan River.

A few kilometers up the same river, Erenio Ofiana and the residents of Sitio Cala-Cala in Bgy. Macasandig suffered the same fate.

The whole sitio of Cala-Cala, Bgy. Macasandig in Cagayan de Oro City was aware that the community, located near the river, could be flooded. However, villagers had weathered previous floods so they thought they would be safe.

Sendong survivor

That night, Ofiana lost his 3 grandchildren and his daughter-in-law to "Sendong".

Mindanao is not usually hit by typhoons. With this in mind, warnings from the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA), were not taken seriously by residents living near major rivers in the island.

Those living along the Cagayan de Oro River in Cagayan de Oro and Mandulog River in Iligan City did not think that their houses would be damaged -- or washed out by floodwaters.

Records from 2010 show Barangay Macasandig, which includes Sitio Cala-Cala, had a population of 23,310. Today, except for the lone structure that survived the flood and now serves as a memorial, not a single house stands in Cala-cala.

Tropical cyclone Sendong affected more than a million people and destroyed or damaged 51,757 houses.

Less than a year later, in the wee hours of December 4, 2012, another strong typhoon hit the island of Mindanao, causing similar deaths and damage as "Sendong."

The night before, on December 3, Joseph Babag watched his family having fun inside their house. His father, mother, grandmother, and siblings were sharing jokes and laughing together, while he was sitting in a corner, watching them. They seemed unaware of a looming disaster that would befall their family.

"I did not know that it was the last time that I will see them," recalled Babag.

The following morning, heavy rains caused by "Pablo" started to pour. Babag and his family were forced to leave their house after a tree fell and destroyed it.

They sought refuge in a nearby health center, but even the building later collapsed. Out of more than 200 people inside the building, only 9 people survived.

Babag was among the 9 who lived.

In the course of his struggle with the elements, Babag tried to take his sister with him, but his sister held on to her mother and their grandmother who were swept by rampaging floodwaters.

“When I was about to carry them, mud flowed into the building. I cannot carry my mother because she was wearing a thick jacket at that time,” narrated Babag.

Floodwaters carried him to New Bataan, which is around 7 kilometers from Bgy. Andap.

Pablo survivor

He lived but his entire family remains missing.

Babag said there was a time that he wished he died with his family.

In Sitio Taytayan, Bgy. Andap, Bonifacio Dumdum and his family were inside their house near a river. They were aware that a strong typhoon was coming.

“Our place is not frequented by typhoons. We did not leave our house because we are not familiar with what a typhoon can bring,” he said.

Heavy rains started to pour early morning the following day. Strong winds started to blow.

He and his family decided to leave their house and saw fallen trees outside. The wind and the rain also damaged their neighbors' houses.

“When I returned, my house was gone. It was washed away by the river,” Dumdum said.

Dumdum’s house was just one among the 216,817 houses damaged by typhoon "Pablo."

It also took the lives of 1,067 people and injured 2,666 others in 34 provinces in the Philippines. Eight hundred thirty-four people went missing.

A total of 121,572 families, or 655,373 people were affected in Compostela Valley.

Almost all the towns in the province were severely affected by "Pablo," with most deaths in the town of New Bataan.

Of the 16 barangays of New Bataan, Bgy. Andap suffered the most from the typhoon. The whole community was washed away when boulders, logs, and mud from the mountains came crashing down, destroying everything on their path and leaving 70 dead, 63 injured, and 281 missing.

It has been a year since the disaster and families are still housed in evacuation centers.

Sitting in a corner of a run-down mansion that serves as an evacuation center, Allan Mercado can only stare into the distance, wondering what fate will bring next.

Yolanda survivor

Mercado and 44 other families are temporarily living in what they call the "White House" in Bgy. 31, Pampango, in Tacloban City.

They share the same fate as 890,895 families in central Philippines who were left homeless after the typhoon.

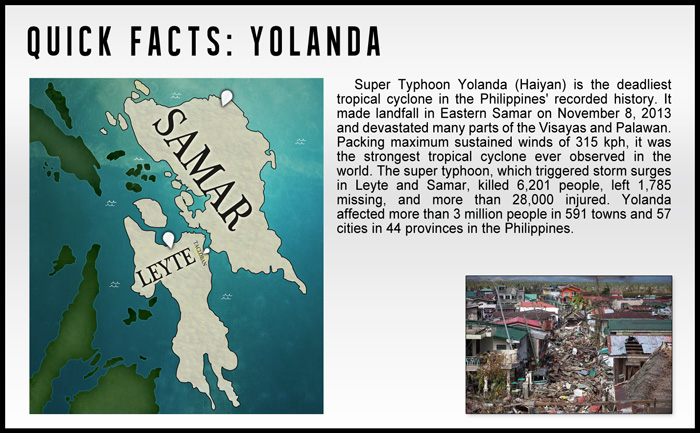

Typhoon "Yolanda" (Haiyan) is the strongest and deadliest typhoon in the country's recorded history. With winds reaching 315 kph, it made landfall over the town of Guiuan, Eastern Samar on November 8, 2013.

"Yolanda" then moved to the west, making landfall 6 times before finally leaving the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR).

The typhoon killed at least 6,201 people, left more than 28,000 injured, with 1,785 others missing, according to the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC).

Tacloban City, with 2,524 deaths, and 594 missing, was among the areas hit hard by the typhoon. Bodies were still being found two months after the typhoon. Survivors have yet to recover from their experience, and most are still unsure of their future.

"Yolanda" also flattened Bgy. Candahug, Palo in Leyte.

Rowena Estoya was patiently waiting for his son, Jason, to come home from his workplace in Samar when village officials informed them that they had to evacuate as a strong typhoon was coming.

Estoya, who lived near the sea, was aware of the dangers of a strong typhoon. Their house had been flooded before.

She packed her bags and prepared to leave.

However, her daughter, Victoria, refused to leave her small store behind. Bernardo, Rowena's husband, also refused to leave the house.

Her two other sons also stayed behind.

She had no choice but to leave her two children and her husband. Accompanied by her grandson and daughter-in-law, Estoya went to a convention center in Palo.

"Had I known that that was the last time that I will see them, I should have forced them to come with me," she said.

Estoya said that they were cowering in fear inside the evacuation center when the typhoon destroyed it.

Yolanda Survivor

She survived the typhoon but found her two sons dead in the afternoon of November 8.

She immediately asked about her other children and her husband, but her sons said they were dead.

"I cried hard. I was not able to see them."

Bgy. Candahug was later dubbed as the "Village of Widows." Most of the 150 people who died in the barangay were men: fathers, brothers, and sons who refused to leave their houses behind.

Among those who died were 3 members of Estoya's family -- her son, husband, and daughter.

Mercado also lost his wife and daughter to the typhoon. He only found his son a day after Yolanda hit.

For the next couple of days, Mercado and his son went from one place to another, looking for their missing family members. They slept wherever possible, eating only when someone offered them food.

He admitted that he found it hard to sleep at night, especially during the first few nights after the disaster.

"Every time I close my eyes, I can see my wife and daughter. I can imagine what they went through during the storm."

He still thinks about his wife and daughter. Mercado knows that he has to be strong for his son.

“I want to start a new life. I threw away all our old clothes. I want to live in another place. This place reminds me of the past,” he lamented.

Mercado is not alone in trying to start a new life. His story is similar to those of the other victims of "Yolanda," "Sendong," and "Pablo."

Two years after "Sendong" hit Cagayan, people are back on Isla Bugnao, living in run-down shacks, eking out a living from the same river that not so long ago took the lives of people they knew.

Noel Labita lives on Isla Bugnao, one of the three islets located along the river. Unlike his neighbors, he intentionally stayed near his house to protect his boats when "Sendong" hit Cagayan de Oro City.

Labita works at a sand quarry. He digs up sand on the riverbed and sells it to construction companies.

Sendong Survivor

Labita has returned to his old house. He repaired the damage caused by the storm and continued living in it as if "Sendong" never happened.

He cannot afford to leave Isla Bugnao, as he has invested a lot in his quarry business. He owns several boats and has established connections with different contractors who buy sand from him.

He is also aware that he will be forced to leave his house, as Isla Bugnao has already been declared unsafe for human habitation.

But Labita and the rest of his neighbors have stayed on Isla Bugnao, braving floods and ignoring the danger so they can provide for their families.

In Cagayan de Oro City, the Task Force on Housing and Shelter said 5,700 families or 60% or victims in the area have already been given new houses.

The remaining 40%, including Labita and his neighbors, are either living with their relatives or have returned to their houses.

Of the 5,700 houses, around 1,800 are uninhabited.

Task Force on Housing

and Shelter, Cagayan de Oro

Around 30% of the victims have been given permanent houses. However, the government has yet to identify relocation sites for the rest of the victims.

Back in New Bataan in Compostela Valley, Beverly Dela Peña of the Municipal Social Welfare and Development Office, said they encountered problems in looking for suitable resettlement areas for the victims.

Municipal Social Welfare and Development Office, New Bataan

According to Osin Sinsuat, chief geologist of the Mines and Geosciences Bureau-Region X (MGB-10), they have been warning people of possible hazards since 2009, especially after tropical storm "Ondoy" hit Manila.

The MGB declared Isla Bugnao, Isla de Oro, and Cala-Cala, all in Cagayan de Oro, unsafe for human habitation.

But their warnings fell on deaf ears.

"Our warnings were ignored. We don't have police power, we can only warn them, but we cannot force them to leave,” said Sinsuat.

“People need first-hand experience before they believe. Now that they have experienced Sendong, they believe our warnings,” he added.

MGB Director Leo Jasareno echoed Sinsuat's opinion. He said that even before "Yolanda" hit the city of Tacloban, they reiterated their warning and identified which areas are at high risk of floods and landslides.

“Yolanda was not the first typhoon of this kind. The country experienced something similar during the Spanish time, but we forgot about our historical records,” he said.

Warnings from the MGB were not the only thing ignored. It seems that the officials of New Bataan, Cagayan de Oro City, and Tacloban City, were not aware of a law on disaster management.

MGB Director

Republic Act 10121, or the Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act of 2010, created the NDRRMC and Local Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Councils (LDRRMCs) in every town and city in the Philippines.

An LDRRMC is composed of heads of several municipal offices such as the local health office, local social welfare and development office, local engineering office, local veterinary office, as well as representatives from the Department of Education (DepEd), Philippine National Police (PNP) and Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP).

One of the major tasks of the LDRRMC is to facilitate and support risk assessments and contingency planning activities, as well as to consolidate local disaster risk information, which include natural hazards, vulnerabilities, and climate change risks, and maintain a local risk map.

Aside from identifying the risks, the LDRRMC is also tasked to manage the hazards, vulnerabilities and risks that may occur in their locality, as well as to formulate counter measures in response to the risks and hazards.

Fernandez said the government of Cagayan de Oro City has yet to create a shelter plan which will identify residential lands. Meanwhile, Dela Peña said they have to look for new resettlement areas in New Bataan after their identified resettlement areas were declared unsafe by the MGB.

The same issues faced by the people of Cagayan de Oro City after “Sendong” and New Bataan after “Pablo” will now face “Yolanda” survivors in Samar and Leyte.

“I have given the government, both previous and present administration, about a hundred recommendations to address the hazards before they become disasters,” said Architect Jun Palafox, a prominent urban and environmental planner.

Palafox is one of the planners who is often consulted after a disaster hits the country. He is now working with Presidential Adviser on Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Panfilo Lacson on a master plan for the rehabilitation of typhoon-struck areas in the country.

Based on his observations, the government could have alleviated the impact of "Yolanda," if only plans were in place beforehand.

“We do not have a tradition of planning,” he said.

Palafox said the Philippines, which is prone to disasters, should have evacuation centers that follow international standards that are resilient to fire, winds, and floods.

Evacuation centers should also have an emergency health center, an emergency shelter, and an emergency telecommunications command center.

“We should stop using schools as evacuation centers,” Palafox said.

He said the country has a lot of obsolete laws such as the Building Code.

He said the existing Building Code only plans for structures that can withstand 220 kph winds. "Yolanda" was packing 315 kph winds.

Architect and Urban Planner

The MGB, in a post-disaster assessment, said all areas 40 meters near shorelines should be declared as no-build zones, especially in flood-prone areas in Tacloban City, including the districts of San Jose, Sagkahan, Bagacay, and Anibong.

The no-build zones can go as far as 200 meters, depending on the area's location.

This means that no house or structures should be built within the no-build zones, as these areas are at high risk of flooding.

Jasareno believes that the Tacloban Domestic Airport should be transformed into a mangrove forest or a public park.

However, he also understands the difficulties in changing people's way of thinking and culture, especially their attachment to their land.

No-build zones will also affect people's livelihood, especially fishermen whose primary source of living is the same sea that can take their lives anytime.

In rebuilding Tacloban City, Palafox believes that the private sector will play a big role in making the process easier and faster.

“The solutions are there, but sometimes, from concept to commitment to completion, it takes years and decades [before a project can be completed],” he said.

He also believes that now is the time to focus on prevention and learn from mistakes in the past.

“But instead of building back better, people are building back worse,” Palafox said.

Like Palafox, Vice-Mayor Jerry "Sambo" Yaokasin of Tacloban City has high hopes for the city.

“When I grow old and my grandchildren ask me what I have done for the city, I hope I will be able to show them a city that will serve as our legacy,” Yaokasin said.

Yaokasin believes that rebuilding Tacloban City is a "once-in-a-lifetime" opportunity. He wants a master rehabilitation plan.

Vice-Mayor, Tacloban City

Given the extent of the devastation the city experienced, he admitted that it is difficult to move towards resettlement unless a government master plan is made.

He said inputs from the city government should be included in the plan.

“It can’t be people from the outside just telling us what they want Tacloban to become. At the end of the day, input from the local government would be very important," the vice-mayor said.

A master plan for the rehabilitation of typhoon-ravaged provinces is still being done, and Palafox, who has worked on disaster rehabilitation before, has some suggestions that he hopes can be implemented in Tacloban City.

For the families ravaged by the storm surge in the Visayas, Palafox suggested building permanent homes that are 42-square meters per family, with separate rooms for children of different genders.

The houses should also be located at a safe distance from the coast, and should be at least three floors high, with the ground floor serving only as parking space.

But these proposals will only remain as such unless the government and those working on the rehabilitation master plan heed the warnings and suggestions from urban planners and the MGB.

Staring out of the window into Cancabato Bay, Yaokasin ponders what the future will bring to the devastated city of Tacloban. Just a few weeks ago, the stench of corpses being processed by the National Bureau of Investigation in the next building still wafted through the air.

Now, as he shuffles in between relief operations, meetings with local and national officials, and presiding over the town council that will have a say in the planning and rehabilitation of his city, he cannot help but dream that it will all go right.

“If we are going to rebuild the city, we should do it right and we should do it well. The money that we are receiving right now that is pouring in, we would never see it in our lifetime again,” said Yaokasin.

But all the money pouring in for rebuilding efforts will never be enough to prepare for future calamities if people are not willing to change and make changes in their lives, said an expert.

Joseph D’Cruz, United Nations Development Programme’s Asia-Pacific environment advisor, faced hundreds of scientists, experts, architects, engineers and urban planners with these challenging realities in a recent forum.

He said that relocating coastal communities, for example, will not work if the settlers themselves are not convinced that moving elsewhere is in their best interest. They will simply move back to their former settlements.

D’Cruz also said that rebuilding is easy, but the challenge is how to build smarter. “I think that focus on that simple, straightforward, cost-effective measures to make our rebuilding more resilient is very, very important; not necessarily the big fancy signature programs but the thousand little tweaks we can make on how we do things,” he said.

Ultimately, it seems that they key to successfully managing future disasters is in the very nature of Filipinos: Their inner strength to bounce back from, and the ability to cope with, any devastation.

The award is among the Asian Environmental Journalism Awards given annually by the Singapore Environment Council to recognize and reward excellence in environmental journalism in Asia.)

Read: ABS-CBNnews.com report bags Asian environmental award

Videos and photographs by Fernando Sepe, Jr.

Graphics by Angela Salano

Developed by Regie Francisco

Additional images by Rem Zamora, Reuters, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and Palafox Associates

Produced by Fernando Sepe, Jr.